Some names and identifying details have been altered to protect the safety and anonymity of the individuals concerned.

Copyright 2018 by Marwan Hisham and Molly Crabapple Inc.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by One World, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

O NE W ORLD is a registered trademark and its colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Some illustrations are based in part on photography or videography posted by Syrian activists, fighters, and civilians on the Internet. The books cover is based on a photograph taken by Tareq.

Some parts of A Russian Feast were adapted from an article written by Marwan Hisham for Foreign Policy.

ONE

RAQQA, 2011

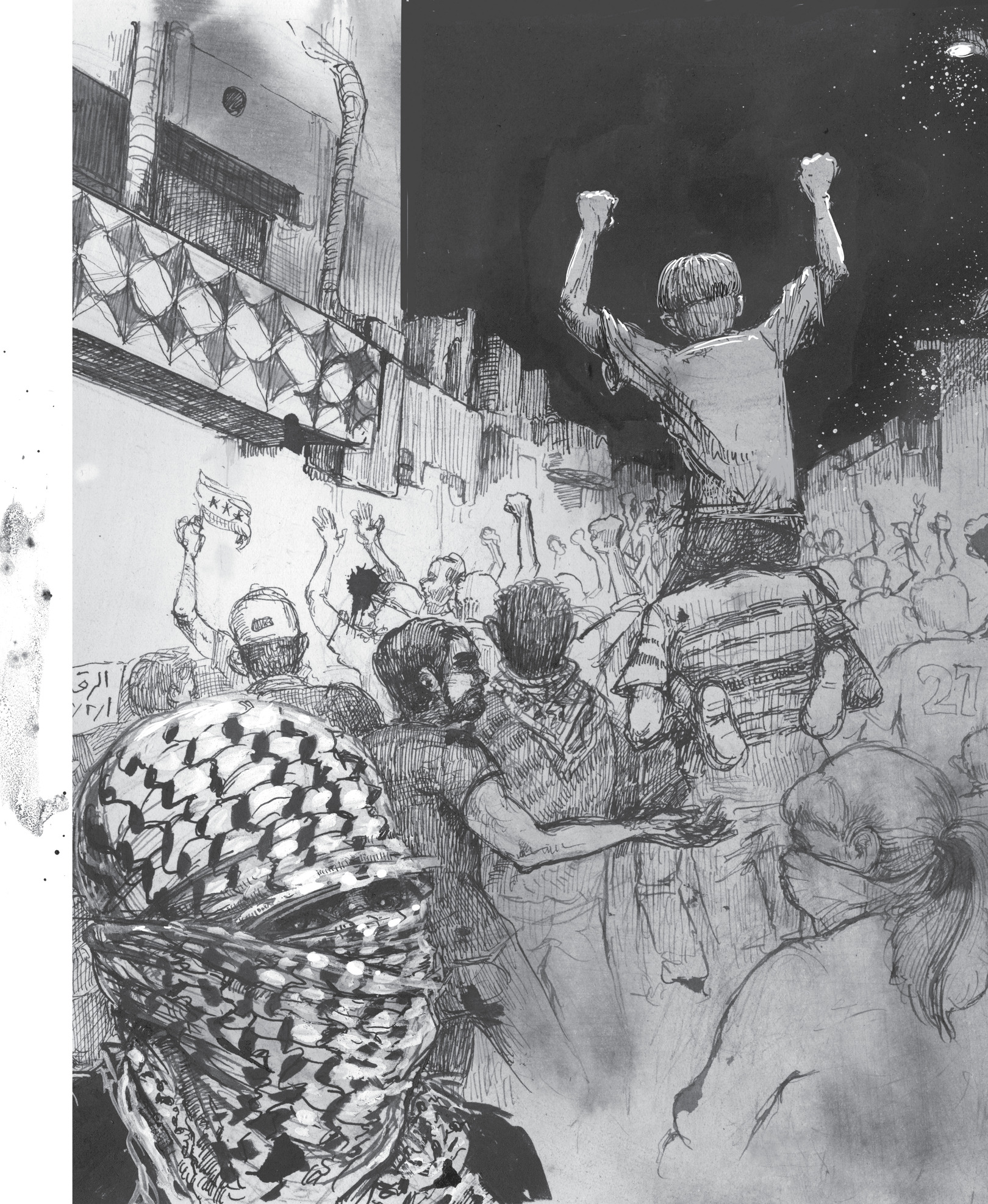

T EAR GAS BURNS OUR EYES.

Nael, Tareq, and I are standing with hundreds of other protesters in the street in front of al-Mansouri Mosque, gagging on the tear gas lobbed at us by the military. Our faces sting, so we wrap them in our T-shirts.

Until five minutes ago, we were chanting, If you have a conscience, join us, but now all we can manage is, Kus ukhtak, ya BasharHey Bashar, fuck your sisters cunt.

I see a gas canister on the ground. It leaks the same foul stuff thats making water stream from Tareqs eyes. I pick it up from the back end so that it wont burn me. My hand screams anyway. I throw it toward the line of riot cops. I dont know where it goes, but I grin anyway, exultant.

It is my first protest.

Fear is dead.

If a bullet hits me now, Ill feel no pain.

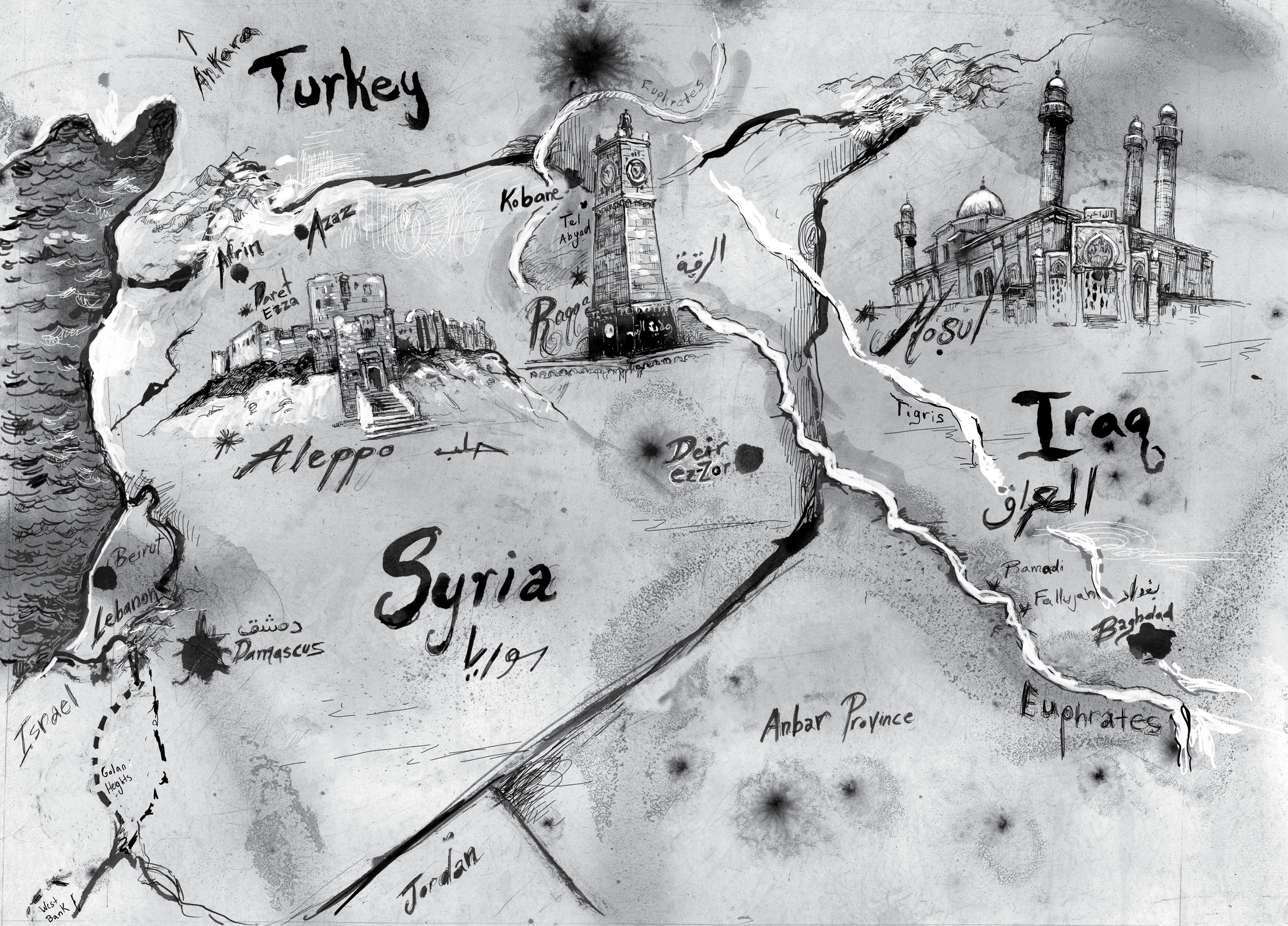

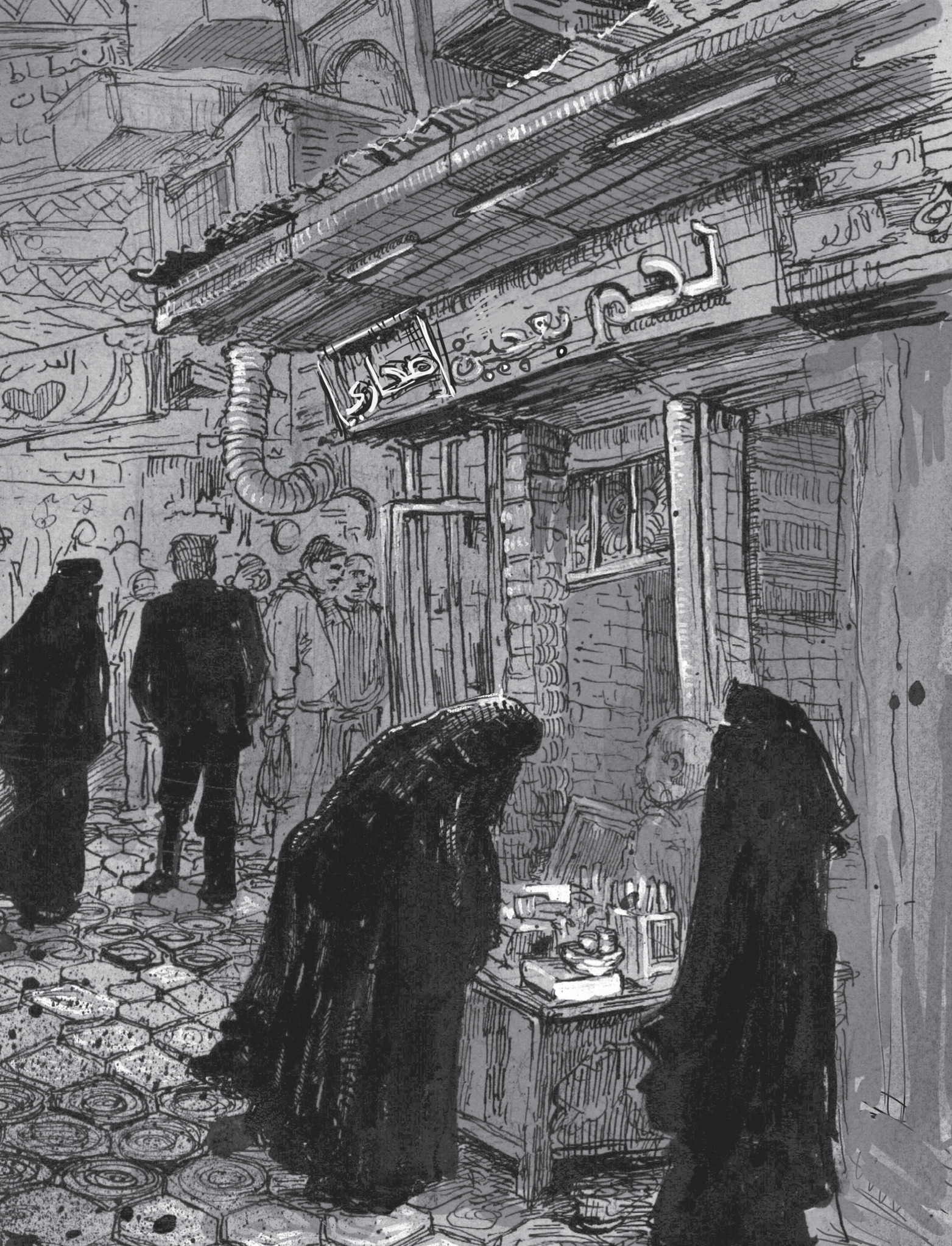

RAMADAN IS DRAWING TO a close, taking with it the sourness of our childhoods, but in Syria, a revolution is being born. It has been six months since the first demonstrators hit Damascuss al-Hamidiyah neighborhood. Their protests consisted of defiant shouts and the sound of their sneakers skidding as they ran through twisted alleyways, the security forces close behind. Now protests bloom in most cities. The country is boiling, but aside from some tiny demonstrations, our Raqqa seems quieta poor, uneducated city, lagging behind, just like it always has.

We are young this summer. I am twenty-two, Nael is twenty-four, and his brother Tareq is twenty-one. We grew up together; we played soccer in the dusty streets beneath the disapproving gaze of our parents. How we longed to escapeand we did: I to study in Aleppo, Nael in Damascus, and Tareq in liberal, libertine Beirut. We are among the first of our families to attend university, but we are still failures in our fathers eyes, who only want us to rise to their level of achievement and no furtherthey fear the victories we might win on our own.

Dusk is falling. The muezzin sings the Maghrib prayer to signal that we can break our fast. We havent eaten since dawn, but food isnt what we are hungry for.

We want to shout our throats bloody. To force the sound of our voices into the most intimidating ears.

Every evening for weeks the same scene has played out at al-Mansouri Mosque in Raqqa. Several dozen protesters merge into the crowds that stream out after prayers. Taking advantage of their relative anonymity, the protesters shout slogans made famous in Egypt or Tunisia for a few thrilling minutes, then vanish into the side streets. For weeks, weve known about these protests, and tonight, for the first time, we hurry to join them. I glance at Nael. His face shines with its usual nervous energy, fueled by the furnace inside him, and I think again that for Nael, the whole world will never be wide enough.

Our parents must not know, he whispers to me. Hes right. Activists are trouble for their parents, especially if theyre caught.

No one must know, I grumble back.

Soon we see more protesters. A few hold Syrias three-starred independence flag, while others wave signs scrawled in Arabic. Only God, Syria, Freedom. Death, but not humiliation. Word spreads that security forces have massed at a junction near the mosque, so we march instead through the nearby al-Hani passageway. We curse recklessly against the powers that be. Hey hey! This is Raqqa! we chant, claiming our citys place in the revolution.

In response, insults pour from every window and balcony. Sons of bitches! Go back to your parents house! the neighbors hiss. You have ruined this country!

God curse you! one old woman screams, her face contorted with hate.

What can she know of our motives or those of the other protesters at these demonstrations blossoming irrepressibly across our country? Her rheumy eyes see nothing but a crowd of brats. To her we are stupid children, behaving badly, in need of our fathers fists. We will never forgive her, nor those like her, I think. Ingrate, I mutter in disgust.

I understand the rich not caring. The well-connected businessmen. The government employees who bought nice cars with the money they got from bribes. The regime turned out well for those people, so why would they spare a thought for others? But how can a working-class Raqqan ever allow him- or herself to be content? Nael told me that when a government keeps kicking people down, they get used to it. Life is shit, they think, and turn for happiness to their personal shit piles. Though we understand the mechanisms of control, neither Nael nor I can excuse this apathy. Even covered in blood, the protesters slaughtered during crackdowns in Homs and Daraa looked more alive than the zombies who curse us from their balconies. History might prove us wrong, but at least we could speak to the people killed when the regime tanks rolled into Deir ez-Zor mere weeks ago.

![Cockburn Patrick - Syria Burning: A Short History of a Catastrophe: [VersoUSAed]](/uploads/posts/book/207719/thumbs/cockburn-patrick-syria-burning-a-short-history.jpg)