REVOLT IN SYRIA

STEPHEN STARR

REVOLT IN SYRIA

EYE-WITNESS TO THE UPRISING

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York

cup.columbia.edu

Stephen Starr, 2012

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-80123-2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Starr, Stephen.

Revolt in Syria : eye-witness to the uprising / Stephen Starr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-70420-5 (alk. paper)

1. Syria--Politics and government--2000- 2. Syria--Social conditions--21st century. 3. Protest movements--Syria--History--21st century. 4. Political violence--Syria--History--21st century. 5. Starr,

Stephen--Travel--Syria. 6. Journalists--Syria--Biography. I. Title.

DS98.6.S73 2012

956.91042--dc23

2012022111

A Columbia University Press E-book. CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the authors nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

CONTENTS

Thirteen women and children have moved into my friends summer house in Hamoryeh [east of Damascus], an accountant told me. He said they had nothing but the clothes on their backs. He was actually crying not because his house was occupied, but because this is what has become of Syria.

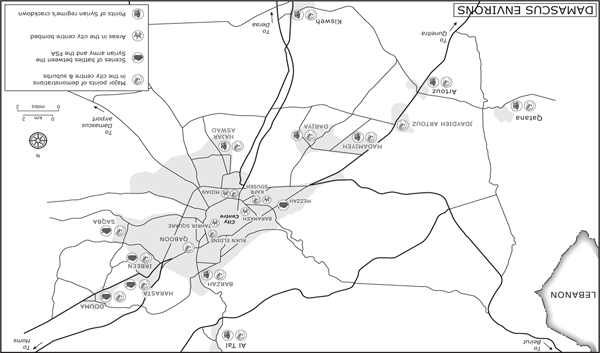

It was early February 2012 and a series of rebellious suburbs and towns east of the capital had just fallen to regime forces.

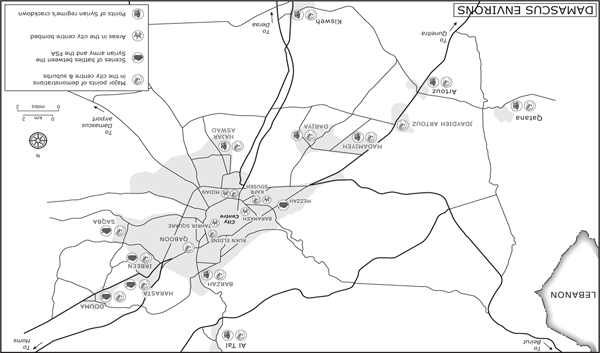

For periods of between a few days and several weeks, rebels from the so-called Free Syria Army mostly defected soldiers from the regular army manned their own checkpoints and protected anti-regime protests only ten kilometres from Damascus city centre.

It was an assignment to one of these suburbs that impelled me to leave Syria after almost five years.

Visiting the scenes in Saqba in eastern Damascus (see ) made me feel as if staying in the country had simply become too risky. Flying out of Damascus airport, where I was questioned for thirty minutes by an official and a military officer, and where tanks surrounded the runway, undetectable from the air, I was filled with relief and regret. I had to sell my apartment. I had to convince myself I was not being overly paranoid. I was leaving behind the news story of the year.

But elements among the myriad state security services knew where I lived, where I went each day and who my friends and acquaintances were. I had five years of roots to be pored over by the relevant authorities, if, when and how they pleased.

The regimes assault on Baba Amr and other dissenting districts of Homs in February 2012 proved a watershed moment for the revolt: had the rebels managed to fend off the regimes brutal attack and actually hold on to territory it could have convinced Syrians (and countries) eager to end the Assad regime that it was a serious, capable entity. Instead, the entire world saw Syrias armed opposition for what it was: a mostly disorganised group with limited capabilities. Neither the political or armed opposition have particularly endeared themselves to the millions of Syrians sitting on the fence or to elements of the international community keen to stop the regimes violence. Rebels fled Homs in early March after a month of intense shelling by regime forces, claiming they wanted to save civilian lives. Many Syrians wondered why they didnt leave a month before and thus spare many hundred more.

The international news circuit was shocked by the deaths of the brave journalists Marie Colvin and Remi Ochlik in Homs on 22 February 2012. But we did not hear how many Syrians were killed (seven) in the same attack. International observers should be more concerned about the stories of the fourteen activists who died attempting to smuggle Paul Conway, the photographer injured in the same shelling that killed Colvin and Ochlik, out of Homs on 28 February. The potential for radicalisation amongst their families and friends probably increased exponentially as a result, perhaps encouraging them to take up arms against the regime. Such stories have been repeated thousands of times around the country.

The Syrian army also quelled dissidence in Zabadani and Harasta around the capital, in Hama, Idlib and several other centres of protest around the country for the umpteenth time in March 2012. But they are hollow victories even as state media claim the revolt is over. As was the case in one town that features prominently in this book, each time the army entered the town protestors quietened, but when it left again the revolutionaries and activists went back to work. They will continue to do so.

The pot of gold cash injection announced at the second Friends of Syria meeting in Istanbul on 1 April smacked of Saudi Arabia and Qatar two leading international denouncers of the regime wishing to exert control in Syria without getting their hands dirty. The move will see the Gulf countries paying the Free Syria Army in an attempt to encourage more defections.

Saudi Arabia was never particularly popular with Syrians before March 2011 and this venture is unlikely to increase further defections (soldiers and officers who may wish to defect are more concerned with staying alive than with promises of bounties). Kofi Annan, the Arab League and UN special envoy to Syria succeeded in getting the regime to agree to an 10 April 2012 deadline for the partial implementation of a proposed peace plan. This plan would see a ceasefire monitoring mission deployed to Syria, the withdrawal of the regimes military forces from urban centres and permission for humanitarian aid to enter the areas most affected by the violence. At the time of writing, the makeup of such a force has not been discussed but it is likely the regime will adopt the same plan it did for the visit of the failed Arab League observer mission.

The Syrian deputy oil minister who defected to the opposition on 7 March counted as the highest ranking government official in a year of revolt, remarkably. Rather than serving as a reflection of a regime crumbling, this was more a reminder of just how tough a nut to crack it has been after a full year of revolt.

The regime has no interest in peace, only in keeping power. As with past plans, it will use this chapter to carry out further crackdowns. Thus far, it has successfully faced down the international community which once proposed UN resolutions calling for Assad to step down. It routed the rebels in Baba Amr, Idlib and elsewhere around the country in February and March 2012. On a certain level, it has never felt stronger and more convinced it can win than it does in April 2012. But perhaps this arrogance will lead to its ultimate downfall.

Conversations among Syrians continue to run in circles. Everyone has the right to be free and to say what he wants, one would say. Free to do what to destroy shops in the name of freedom because they hate Bashar al-Assad? This is not freedom, went the reply over coffee and cigarettes all over the country time and time again. This is perhaps the most worrisome aspect I have observed during the revolt. Today in Syria people are cast and characterised as being either with or against the regime. Children go around the school yard asking each other this question, where the seeds of a new divided generation are budding. The space for discussion and debate that flourished as the revolt spread last spring has unfortunately been lost as the death count rises and as people are forced to take sides.

Next page