Ta lal (Hanins father, from Blouta in Latakia Province, living in Mezzeh 86 in Damascus) and Awatif (Hanins mother)

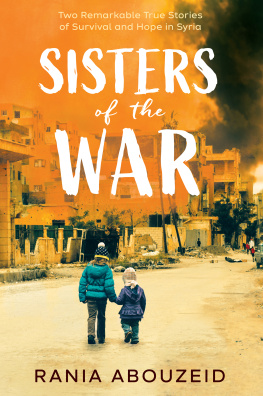

Out of suffering have emerged the strongest souls; the most massive characters are seared with scars

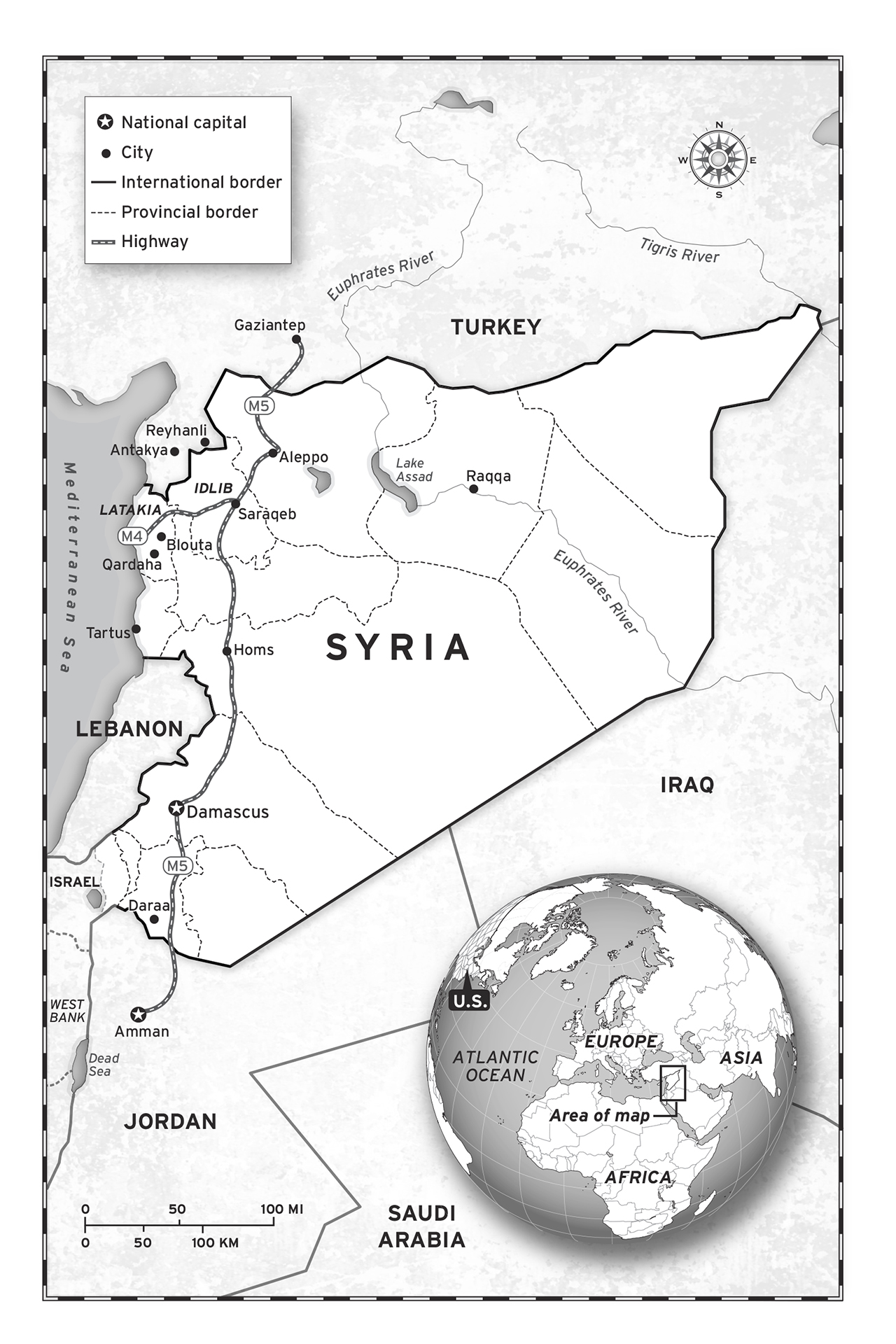

T he three sistersLojayn, Hanin, and Jawaknew they lived in a special place, an ancient city where history wasnt confined to books; it was alive and all around them. The Syrian capital, Damascus, was one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world, a place that countless generations had called home for many thousands of years. The girlsten-year-old Lojayn, eight-year-old Hanin, and Jawa, who was almost sixdidnt live in the capitals fancy parts, in its rich neighborhoods or historic districts; they lived on its fringes, on a hill in an overcrowded slum called Mezzeh 86. Still, they were proud to say they were from Damascus, even if their sliver of it was its poorer outer edge.

Relative to the grand old capital, with its long, rich history, Mezzeh 86 was practically brand-new. It had sprouted up in the 1980s, a chaotic burst of concrete not far from the Presidential Palace. It was a messy maze of cramped buildings so close their thin outer walls kissed. The proximity and cheap building materials meant neighbors could sometimes hear conversations in other homes. It was noisy, with potholed streets that puddled in the winter, the plonk, plonk, plonk of raindrops falling on tin roofs setting off a symphony of sound. Honking drivers navigated narrow, sharply sloping two-way streets that were barely wide enough for one-way traffic. Too many people in too small a space, but to the sisters, the bustle made it feel more alive.

The family lived in a small four-room apartment off the busy main road. Their first-floor home had only one bedroom, which their parents used, so Lojayn, Hanin, and Jawa all slept in the living room on thin mattresses that doubled as floor couches during the day. The young sisters all had full rosy-red cheeks and brown eyes. They all wore their curly brown hair short but still long enough for the colorful clips and headbands and ribbons they loved to wear. They had a new baby brother, Wajid, just a few months old, who filled the small house with joy (and screams and wailing). Wajids arrival meant Jawa was no longer the youngest child. She wasnt overly jealous or resentful of her changed status (perhaps just a bit), but she felt shed outgrown being the baby of the family. After all, she was about to start school later that year. She looked forward to September, when she would join her sisters on the curb outside their home every morning as they waited for the minivan that would drive them to and from classes.

The older girls, Lojayn and Hanin, were also enrolled in a music school a short walk from their home, and Jawa hoped to join her sisters there, too. By early 2011, Lojayn had five years of violin lessons under her belt and was good enough to perform in two concerts with her class at the neighborhoods cultural center. Hanins chosen instrument was the piano. Shed only just begun studying it in 2010, but it came naturally to her. It was very easy for me, she said. Her electronic keyboard, propped on its metal stand, had pride of place in the living room. She was always careful during practice to turn the volume down in case it disturbed the neighbors, but the neighbors never complained. Jawa hadnt yet decided which instrument she wanted to play, although both of her sisters gave her lessons on their instruments. She preferred the piano to the violin.

The sisters were encouraged to express their creativity and to develop a love of the arts, both by their father, Talal, a poet, and by their mother, Awatif. Their small apartment was full of music and literature and drawings the girls made that their mother proudly taped to the walls. On occasion, Talal would read his work to his daughters. They listened in awe, not always understanding all of the words (especially Jawa) but feeling their meaning and the power of their impassioned delivery. Lojayn had even taken to writing poems of her own, hoping to emulate the father she so looked up to. Although Talal had published several books of his work, his poetry couldnt feed his family. To earn a living, he owned a small store in the neighborhood that sold perfume, cosmetics, and hair accessories.

We used to go to Babas store often, Hanin remembered, and every time we drew something Baba would display it in the store to show all the customers! The girls sometimes volunteered to stock the shelves in their spare time, for pocket money. Theyd line up the hair dyes by order of number and color, smell the new perfumes, and arrange the hair accessories. Jawa usually spent her pocket money on ice cream and cookies. They wouldnt really work; it was more like play, but they felt like they were helping out, Talal said. We were very happy in that house. Everything was wonderful.

Outside of the girls happy bubble, many things in Syria were less wonderful. Bashar al-Assad had been president all their lives, and Talals daughters (at least the two older ones) knew that Bashars late father, Hafez al-Assad, had ruled Syria as president before him. That was about the extent of what they knew about their system of governance and the Assad familys role in it.

In 1946, the same year Syria gained independence from France, a then-sixteen-year-old Hafez al-Assad joined a political organization called the Baath Party as a student activist. The next few years in Syria were a period of great instability and short-lived coups, with a parade of leaders who were overthrown and replaced. In 1952, Hafez entered the Homs Military Academy, and later graduated as an air force pilot. By 1963, he had risen through the ranks to become the head of the Syrian Air Force. That same year, he was among a group of Baath Party supporters in the Syrian military who helped the party seize control of the country.

Syrias Baath Party, like most of the secular movements sweeping to power in the 1950s and 60s across the Middle East, preached that all citizens were equal and deserved rights and opportunities. Its idealistic guiding principles were expressed in its slogan: Unity (of the divided Arab states in the Middle East), Freedom (from foreign powers and tyranny), and Socialism (a political and economic philosophy that believes that resources and means of production should be collectively owned and distributed by a community). For Syrias Baath Party, socialism was the means by which citizens from any religious, socioeconomic, or geographic background could improve their circumstances, aided by the firm guiding hand of the state. At least, thats what the party promised on paper. In reality, Syrias Baath Party, like many of the secular movements in power across the Middle East, birthed a dictatorship, and Hafez al-Assad would soon be cast in the role of dictator.

![Cockburn Patrick - Syria Burning: A Short History of a Catastrophe: [VersoUSAed]](/uploads/posts/book/207719/thumbs/cockburn-patrick-syria-burning-a-short-history.jpg)