NO TURNING BACK

LIFE, LOSS, AND HOPE IN WARTIME SYRIA

RANIA ABOUZEID

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

INDEPENDENT PUBLISHERS SINCE 1923

NEW YORK | LONDON

FOR MY PARENTS, MY SISTERS, MY FAMILY

I carried your love and support in my heart every time I crossed the mountains, while on my shoulders I bore the guilt of taking you with me

CONTENTS

_______

_______

This is a book of firsthand reporting, investigated over six years and countless trips inside Syria, Turkey, Jordan, Lebanon, Washington, and several European towns and cities. It tells but a sliver of the Syrian tragedy, how a country unraveled one person at a time.

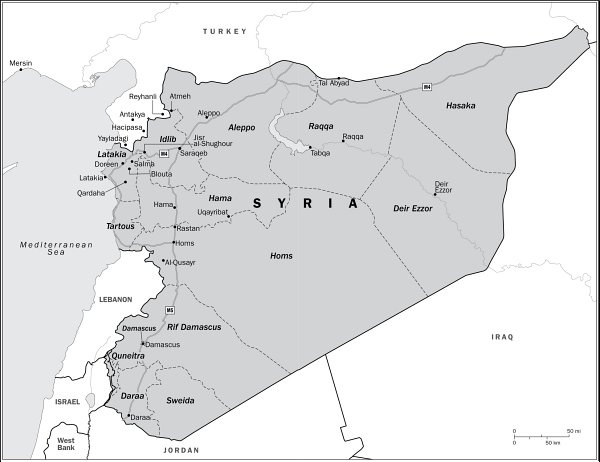

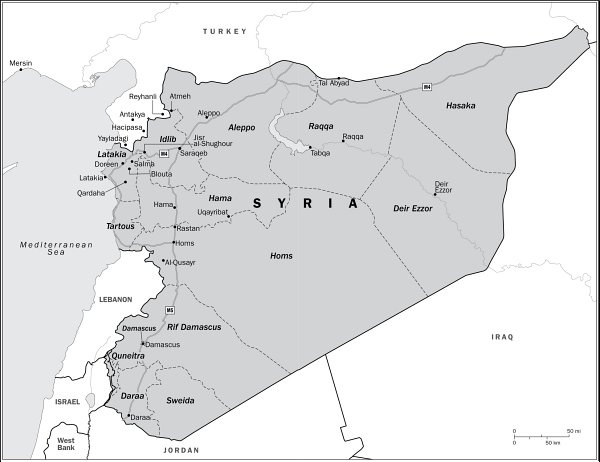

Syria has ceased to exist as a unified state except in memories and on maps. In its place are many Syrias. The war there has become a conflict where the dead are not merely nameless, reduced to figures. They are not even numbers. In mid-2013, the United Nations abandoned trying to count Syrias casualties due to the difficulty of verifying information, although estimates put the death toll at well over 500,000 people. Half of Syrias population of twenty-three million is now displaced. No life is inconsequential. Each is a thread in a communal tapestry, holding the larger intact.

In the summer of 2011, I was blacklisted by the Syrian regime, but not as a journalist. Instead, I was branded a spy for several foreign states, placed on the wanted lists of three of the four main intelligence directorates in Damascus, and banned from entering the country. This forced me to focus on the rebel side by illegally trekking across the Turkish border into northern Syria, although I still managed a few trips to government-held areas. I state this only by way of introduction. This book is not another reporters war journal. I went to Syria to see, to investigate, to listennot to talk over people who can speak for themselves. They are not voiceless. It is not my story. It is theirs.

I did my own fixing, translating, transcribing, logistics, security, research and fact-checking. Any errors are hence mine alone. There are no composite characters, although some names have been changed to protect identities. Some of the people in these pages are now dead, others have disappeared or are in exile, and some are still inside a country that no longer resembles one. Everything I recount is true to the best of my knowledge.

These things happened.

These things continue to happen.

Some of these things should never happen again.

A portion of my earnings from this book will be donated to Inara, an apolitical nonsectarian charity that provides life-altering medical care for children from conflict areas who have catastrophic injuries or illnesses and are unable to access treatment due to war. Founded by CNN correspondent Arwa Damon, Inara is a 501c3 registered charity in the state of New York, and operates across the Middle East. (www.inara.org)

_______

I have employed the Arabic use of kunyas , nicknames that start with Abu or Um (father of or mother of), which are commonly used even if a person is childless. They are informal, respectful manners of greeting and also serve as noms de guerre.

I N R ASTAN

Suleiman Tlass Farzat. The wealthy manager of an insurance office in Hama, who became a civilian activist in his hometown of Rastan.

Samer Tlass . Suleimans cousin, a lawyer.

Maamoun. A mobile-phone repairman-turned-civilian activist.

Merhi Merhi . A civilian activist.

M ohammad Darwish . A student who sparked Rastans first protests and often led chants.

First Lieutenant Abdel-Razzak Tlass. One of the earliest defectors, a member of the Khalid bin Walid Battalion and later a leader of the Farouq Battalions in Homs. Suleimans relative.

N ON F REE S YRIAN A RMY I SLAMISTS

Mohammad (from Jisr al-Shughour). Grew up in Latakia. A former prisoner in Damascuss Palestine Branch and a member of Jabhat al-Nusra.

Abu Ammar . Mohammads childhood neighbor.

Abu Othman . An Islamic legal scholar (or Shariiy ) from Aleppo. Mohammads onetime cellmate in Palestine Branch and a prisoner in Sednaya.

Abu Mohammad al-Jolani . The leader of Jabhat al-Nusra, an Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) offshoot established in Syria in summer 2011 and Al-Qaedas Syria branch.

Abu Maria al-Qahtani . An Iraqi who served as Jabhat al-Nusras lead Shariiy . Jolanis deputy.

Saleh . A former Sednaya Prison detainee from eastern Syria. Part of Nusras inner circle.

Abu Loqman . Salehs former cellmate in Sednaya Prison and, later, ISISs emir in Raqqa.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. The Iraqi leader of the Islamic State of Iraq and, later, ISIS. Self-proclaimed caliph.

Abu Mohammad al-Adnani . A Syrian, and Jabhat al-Nusras chief amni (security agent) before he was appointed the ISIS spokesman.

Firas al-Absi. A nonAl-Qaeda militant stationed at Syrias Bab al-Hawa border with Turkey.

T HE F REE S YRIAN A RMY

Abu Azzam (Mohammad Daher). A fourth-year Arabic-literature university student in Homs. From Tabqa, eastern Syria, he became a commander in the Farouq Battalions.

Bandar. A university student from eastern Syria, Abu Azzams sometime roommate in Homs.

Bassem. Bandars brother and Abu Azzams colleague in the Farouq Battalions.

Abu Hashem (Hamza Shemali). A realtor-turned-Farouq foreign liaison who later headed the Hazm Movement.

Abu Sayyeh (Osama Juneid). A lawyer-turned-Farouq military commander.

Sheikh Amjad Bitar . A cleric from Homs and key Farouq financier.

Bilal Attar and Abulhassan Abazeed . The founders of the Shaam News Network (SNN) and, later, senior members of the Farouq Battalions.

Okab Sakr . A Lebanese politician and member of Saad Hariris Future Movement political party.

General Salim Idris . The head of the FSAs Supreme Military Council.

I N S ARAQEB

Ruha. A nine-year-old girl (in 2011).

Maysaara (Ruhas father) and Manal (Ruhas mother).

Alaa, Mohammad, Tala, Ibrahim. Ruhas siblings.

Zahida. Ruhas grandmother.

Mariam. Ruhas aunt.

Mohammad. Ruhas uncle, married to her Aunt Noora.

I N L ATAKIA

Talal , an Alawite from Blouta, Latakia Province, living in Damascus.

Lojayn , 13 (in 2013), Hanin (10), Jawa (8). Talals daughters.

Dr. Rami Habib. A physician operating a field clinic in the town of Salma.

_______

Revolution is an intimate, multipart act. First, you silence the policeman in your head, then you face the policemen in the streets. In early 2011, the Middle East was electrified by an indigenous democratic fervor, not the cynical imported kind that exploited the slogans of democracy to cloak military coups and foreign interventions. Ordinary men and women unlearned fear. Their demands, powerful in their simplicity, ricocheted from Tunisia to Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, and Yemen: Dignity! Freedom! Bread! They didnt call it a spring. This was a new revolutionary pan-Arabism, born of shared humiliation and frustration, spread by the tools of social media and satellite television. In Syria, it began timidly, with small public gatherings in solidarity with protesters elsewheresuch as the one on February 23, 2011, in front of the Libyan Embassy in Damascus, and the detention in the southern city of Daraa of a group of teenagers accused of writing antiregime graffiti on school walls.

Protests were banned in Syria under an emergency law in place since 1963as long as the ruling Baath Party. News of the vigil on February 23 spread through word of mouth and Facebook, the social platform recently unblocked by the government (to better monitor calls for dissent, many suspected). The plainclothes, not-so-secret, police, or mukhabarat , arrived more than forty minutes before the scheduled 5 p.m. start, followed by black-clad policemen carrying Kalashnikovs. Antiriot police, in olive-green uniforms and black helmets, transparent face shields at the ready, blocked both ends of the narrow, tree-lined street housing the Libyan Embassy. They wielded worn truncheons, the stumpy ends flayed of the black skin that still covered their handles. Thered been a small, peaceful vigil in the same place the night before, but this night would be different.

Next page