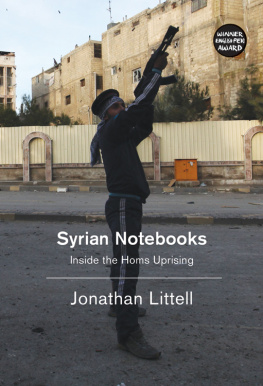

Syrian Notebooks

Inside the Homs Uprising

January 16February 2, 2012

Jonathan Littell

Translated by Charlotte Mandell

This book has been selected to receive financial assistance from English PENs PEN Translates! program, supported by Arts Council England. English PEN exists to promote literature and our understanding of it, to uphold writers freedoms around the world, to campaign against the persecution and imprisonment of writers for stating their views, and to promote the friendly cooperation of writers and the free exchange of ideas. www.englishpen.org

First published in English by Verso 2015

Translation Charlotte Mandell 2015

Introduction Jonathan Littell 2015

First published as Carnet de Homs: 16 janvier2 fvrier 2012

Gallimard 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-824-3

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-826-7 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-825-0 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Littell, Jonathan, 1967

[Carnets de Homs. Engish]

Syrian notebooks / Jonathan Littell.

pages cm

Translation of: Carnets de Homs : 16 janvier2 fvrier 2012; first published: Paris : Gallimard, 2012.

ISBN 978-1-78168-824-3 (hardback : alkaline paper)

1. SyriaHistory, Military21st century. 2. RevolutionsSyriaHistory21st century. 3. Civil warSyriaHistory21st century. 4. Homs (Syria)History, Military21st century. 5. Homs (Syria)Social conditions21st century. 6. War and societySyriaHomsHistory21st century. 7. Littell, Jonathan, 1967TravelSyria. 8. Foreign correspondentsSyriaBiography. I. Title.

DS98.6.L5713 2015

355.0095691042dc23

2014048357

Typeset in Monotype Fournier by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh, Scotland

Printed in the US by Maple Press

Table of Contents

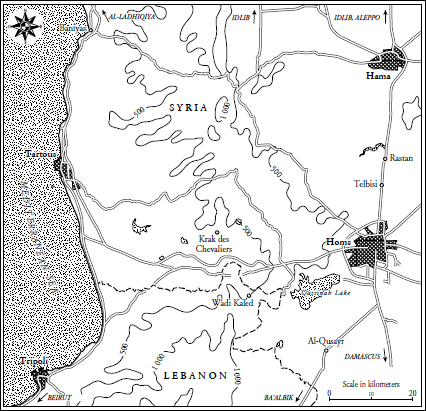

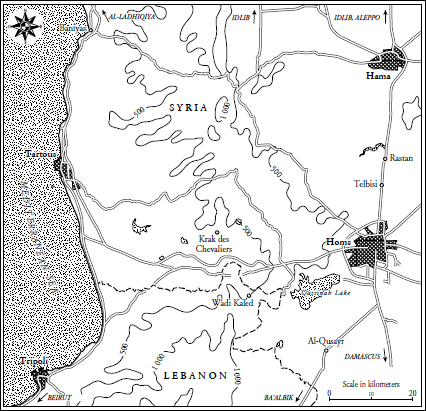

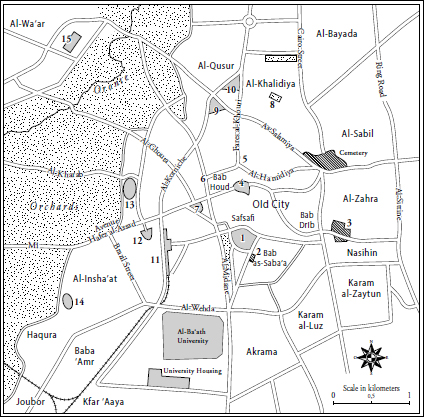

Homs and the Border Region

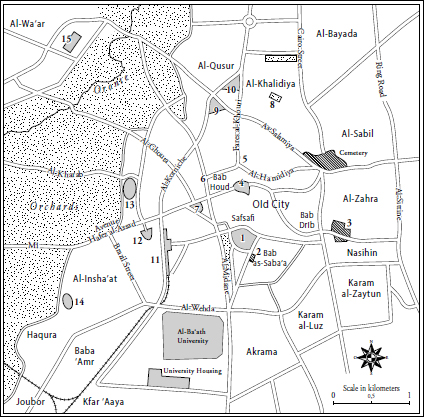

City of Homs

1- Citadel of Homs

2- Bab as-Sabaa Cemetery

3- Bab Drib Cemetery

4- Souk

5- Old Clock Tower

6- City Center (New Clock Tower)

7- Mosque Ad Droubi

8- Square of Free Men (Al-Khalidiya)

9- National Hospital

10- Bus Station

11- Homs Station

12- Safir Hotel

13- Khalid ibn Walid

14- Al-Bassel Stadium

15- Military Hospital

The world is not yours alone

There is a place for all of us

You dont have the right to own it all.

An anonymous Syrian yelling in the night

at a regime sniper, in footage included

in the film Silvered Water

It starts, as always, with a dream, a dream of youth, liberty, and collective joy; and it ends, as all too often, in a nightmare. The nightmare still goes on and will last much longer than the dream: struggle as they can, no one knows how to wake up from it. And it keeps spilling over, infecting ever wider zones, all the while seeping through our screens to come lap up against our gray mornings, tingeing them with a distant bitterness we do our best to ignore. A vague and remote nightmare, highly cinematographic, a kaleidoscope of mass executions, orange jumpsuits, and severed heads, triumphant columns of looted American armor, beards and black masks, and a black banner all too reminiscent of the pirate flags of our childhoods. Spectacular images that have served to mask, even erase, those forming the undertow of the same nightmare: thousands of naked bodies tortured and meticulously recorded by an obscenely precise administration, barrels of explosives tossed at random on neighborhoods full of women and children, toxic gasses sending hundreds into foaming convulsions, flags, parades, posters, a tall smiling ophthalmologist and his triumphant re-election. The medieval barbarians on one side, the pitiless dictator on the other, the only two images we retain of a reality far more complex, opposing them when in fact they are but two sides of the same coin, one coin among many in a variety of currencies for which no exchange rate was ever set.

The notes that form this book are a record of a brief fragment of the dream: a dream that was already assailed on all sides and subjected, as we will see, to unutterable violence, but one that the dreamers still clung to, with all their heart and all their strength. Publishing them now, reopening this small window on three weeks lost in the distant past three years ago, an eternity may at least serve this purpose: to remind the reader that before the nightmare, a nightmare so dense and opaque it seems to have no beginning, there had been the dream. And that whereas nightmares are a roiling magma of individual pulsions, deriving their shape only from the hollow molds of ideology, and adding up to nothing but death, dreams are collective, political, spiritual, social. Perhaps then, these notes might help provide a touchstone, a reference point, to show that all this did not happen by chance; more importantly, that all this did not have to be, that there were other paths, other possibilities, other futures. That the mantra so tirelessly repeated by our solemn leaders, There is nothing we could have done, is simply not true. And that without our callous indifference, cowardice, and short-sightedness, things might have been different.

When the photographer Mani and I arrived in Homs, in mid-January 2012, the Syrian revolution was reaching the end of its first year. In the city and the surrounding towns, the people were still gathering daily to demonstrate calling for the fall of the regime, loudly asserting their belief in democracy, in justice, and in a tolerant, open, multi-confessional society, and clamoring for help from outside, for a NATO intervention, for a no-fly zone to stop the aerial bombardments. The Free Syrian Army (FSA), made up mostly of Army and secret services deserters disgusted by the repression, still believed its primary mission was defensive, to protect the opposition neighborhoods and the demonstrations from the regime snipers and the feared shabbiha (mafia thugs, mainly Alawite in Homs, formed into militias at the service of the al-Assad family). The Syrian citizen-journalists, like those that helped, guided, and protected us during our stay, still believed that the constant flow of atrocity videos they risked their lives every day to film and upload on YouTube would change the course of things, would shock Western consciousnesses and precipitate strong action against the regime. The people still believed that song, dance, slogans, and prayer were stronger than fear and bullets. They were wrong, of course, and their illusions would soon drown in a river of blood. America, traumatized by two useless and disastrous wars to the point of forgetting its own founding myth that of a people rising against tyranny with their hunting guns, helped only by indomitable spirit and idealism stood back and watched, petrified. Europe, weakened by economic crisis and self-doubt, followed suit, while the regimes friends, Russia and Iran, occupied every inch of the political space thus made available. And geopolitics is always written with the blood of the people. The day after I left Homs, on February 3, a series of mortar shells targeted the neighborhood of al-Khalidiya, where I had spent so much time, killing over 140 civilians. As Talal Derki, the Syrian director and narrator of the magnificent documentary