MARIA H. LOH

Copyright Maria H. Loh 2019

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers

Page references in the Index match the printed edition of this book.

1 View north from Pieve di Cadore.

Introduction:

Abracadabra

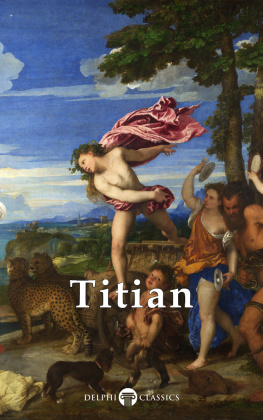

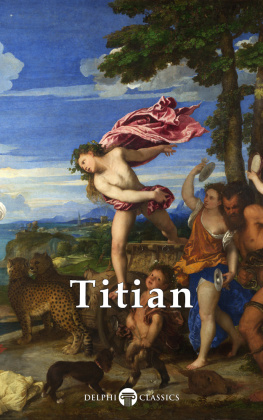

IGMENTS, SPICES, SCHOLARS and slaves. Pilgrims, Protestants, gossip and gold. Venice had always been a city of flow. In the sixteenth century, it stood at once upon the old world of commerce and trade with its relentless movement of goods and upon the new worlds that were being opened up to the literate citizen by printed books. This confluence of things and thoughts brought the imaginary and faraway both delightfully and dangerously close for inspection. From luxury commodities to heretical beliefs, from translations of ancient classics to new, exotic species of plants and animals, the pleasure of variety, difference and possession in this circulatory world in flux is evident in Titians art.

IGMENTS, SPICES, SCHOLARS and slaves. Pilgrims, Protestants, gossip and gold. Venice had always been a city of flow. In the sixteenth century, it stood at once upon the old world of commerce and trade with its relentless movement of goods and upon the new worlds that were being opened up to the literate citizen by printed books. This confluence of things and thoughts brought the imaginary and faraway both delightfully and dangerously close for inspection. From luxury commodities to heretical beliefs, from translations of ancient classics to new, exotic species of plants and animals, the pleasure of variety, difference and possession in this circulatory world in flux is evident in Titians art.

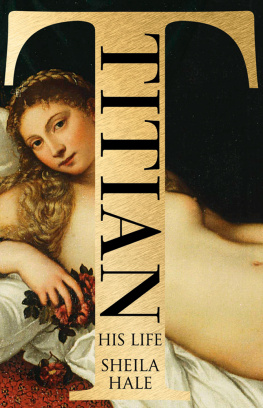

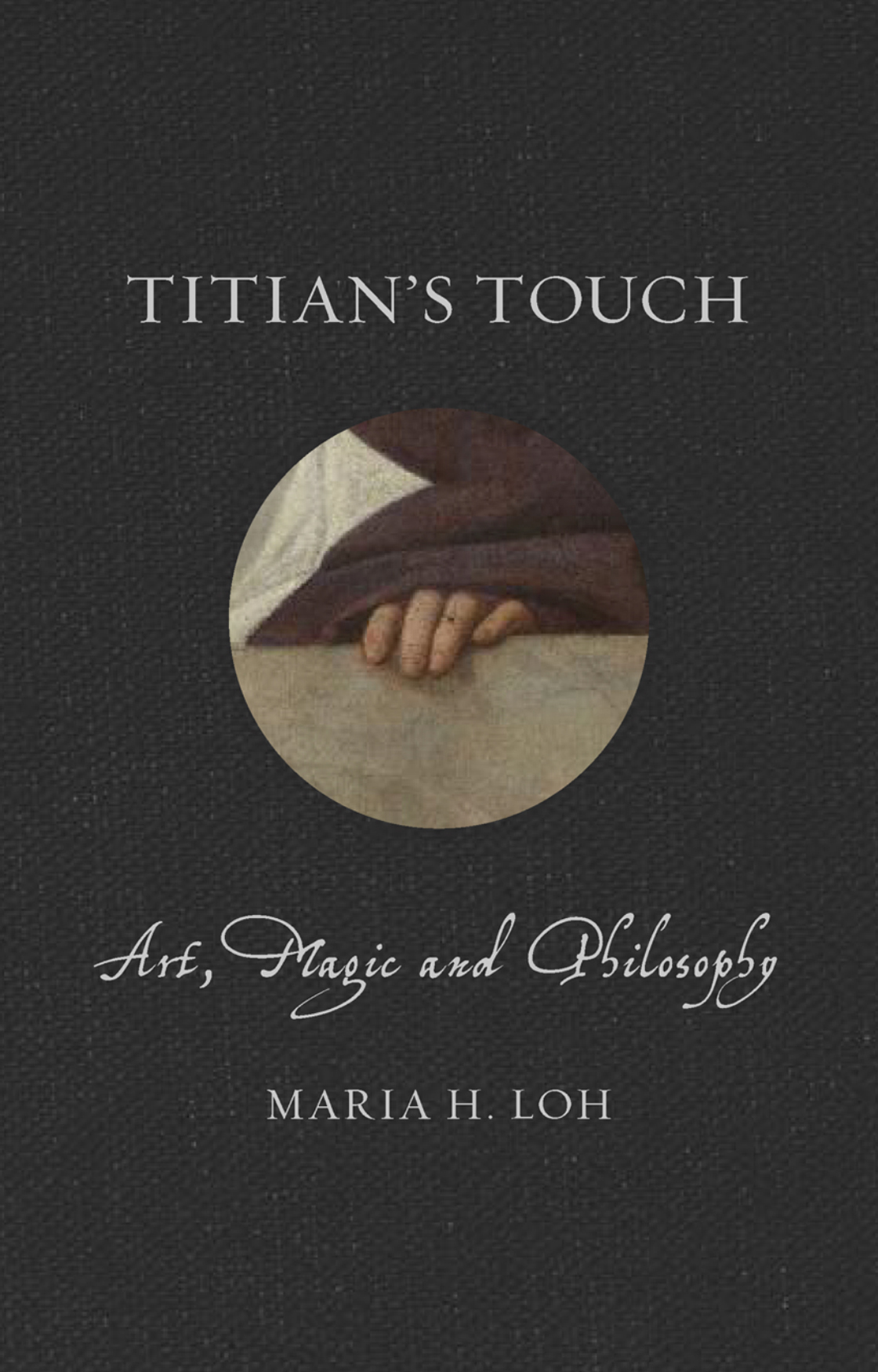

According to legend, the young boy made his first painting with the nectar from flowers derived from the woods around his hometown of Pieve di Cadore in the vertiginous slopes of the Dolomites ( Indeed, throughout Titians long, prolific career (c. 14901576), he was experimental, modern and forward-looking, but his visual practice did not entirely jettison the conventions and convictions that had been inherited from ancient and medieval authorities. In this regard, he was a painter of contradiction and a master of synthesis.

Titian was an extraordinarily gifted storyteller, but he was also a formidable historian. His works preserve within them some trace of the anxieties, concerns, dreams and hopes of early modern Venice. This is not to say that the artists images functioned merely as a mirror of his times. Rather than a direct imitation of the natural world that he saw around him, Titians exploration into the very nature of things was a form of visual philosophy that resonated with the cutting-edge investigations taking place in the nearby university town of Padua as well as the new technologies and trade secrets being developed in the ship yards, apothecaries and silk and gemstone industries in the city. He was a man fully embedded in the world, at once a painter, a philosopher and a sorcerer. His brush, like a magicians wand, possessed the uncanny power to change oil, dust and threads into immortal objects of desire. His contemporaries claimed that everything he touched was inspirited and came to life, and his friend Pietro Aretino raved: Titian held the sense of things in his brush.

The difficulty in writing a monograph focused on an artist as famous and as beloved as Titian is to tell a compelling story without rehashing the same old tales. Writing in the long shadow of Joseph Archer Crowe and Giovanni Battista Cavalcaselles unsurpassed biography of the artist (1877) and Harold E. Wetheys formidable catalogue raisonn (196975), subsequent scholars have approached Titian and his art either from the text-based interests of the iconographer concerned with meaning or from the perspective of the social historian who asks questions about gender, the status of patrons, and the cultural, commercial and political world in which the artist operated. Following an essay by David Rosand on The Eloquence of Titians Brush (1981), some of the most innovative scholarship in recent decades has focused on the artists painterly exploration of materiality, the body and the senses. Drawing from this rich arsenal, I would like to demonstrate further that these fleshy, earth-bound conditions embrace profoundly philosophical concerns as well.

What can Titians paintings tell us about his world? This is essentially a historical question, to which a philosophical one can be added: how do we think with Titians paintings? This double-sided proposition might be restated in the following manner: how is the world engendered in an image, but how, too, does the visual explore and interrogate the world? To respond to these questions and by way of introduction to Titians pictorial intelligence, I offer an extended consideration of two of his most profound works. The first presents an unidentified female sitter from around 1511; the second portrays a falsely accused archbishop twice painted in the 1550s.

This book, in contrast, will show the reader how to look at works for a long time. The process will be accumulative: we begin with a few in-depth studies and expand to a larger repertoire of thematic considerations. With paintings of the distant past, modern viewers are often daunted by the sheer amount of contextual knowledge that seems to be required in order to decipher the identity of this or that saint, goddess, historical personage or locale. Without easy access to this data, one can feel at a loss as to where to begin. A good painting, however, can and should communicate so much more, and Titian it cannot be denied was a painter of some very good paintings. A secondary aim of this book, therefore, is to demonstrate to the non-specialist how to look a painting in the eye, so to say. The following chapters will take up this task moving roughly chronologically, but above all thematically through some of Titians most startling paintings. Relevant historical details and summaries of previous interpretations will be provided when necessary to help guide the unfamiliar reader, and some new (and often provisional) theories will be presented for consideration. At the centre of the story, however, will be the conceptual, material and magical work of the paintings themselves, images at once ambivalent and ambiguous, presenting the viewer with the sensible realities of nature through the abstract perfection of art, blurring the distinction between reality and fiction. The aesthetic force of Titians art, as we shall discover, resided precisely in this nebulous in-between, which was simultaneously too real and too ideal, too concrete and too abstract, too sensory and too conceptual.

IGMENTS, SPICES, SCHOLARS and slaves. Pilgrims, Protestants, gossip and gold. Venice had always been a city of flow. In the sixteenth century, it stood at once upon the old world of commerce and trade with its relentless movement of goods and upon the new worlds that were being opened up to the literate citizen by printed books. This confluence of things and thoughts brought the imaginary and faraway both delightfully and dangerously close for inspection. From luxury commodities to heretical beliefs, from translations of ancient classics to new, exotic species of plants and animals, the pleasure of variety, difference and possession in this circulatory world in flux is evident in Titians art.

IGMENTS, SPICES, SCHOLARS and slaves. Pilgrims, Protestants, gossip and gold. Venice had always been a city of flow. In the sixteenth century, it stood at once upon the old world of commerce and trade with its relentless movement of goods and upon the new worlds that were being opened up to the literate citizen by printed books. This confluence of things and thoughts brought the imaginary and faraway both delightfully and dangerously close for inspection. From luxury commodities to heretical beliefs, from translations of ancient classics to new, exotic species of plants and animals, the pleasure of variety, difference and possession in this circulatory world in flux is evident in Titians art.