Table of Contents

For my family

Acknowledgments

When I started to research the Black and White Ball, I imagined that unearthing material from the 1960s would be easier than excavating the 1880s, as I did in my previous book. I was surprised to discover that recent history can be more elusive than the distant past. Consequently, I am extremely grateful to the many eyewitnesses whose vivid memories helped to bring this extraordinary moment in 1966 to life. Special thanks to the delightful Elizabeth Hylton and Susan Payson Burke for their invaluable assistance, sage advice, and constant good humor. Thanks as well to Adolfo Sardia, Don Bachardy, Ann Birstein, Bill Berkson, Kenneth Paul Block, Joanne Carson, Peter Duchin, Joe Evangelista, Tom Fallon, Kitty Carlisle Hart, Ashton Hawkins, Kenneth Jay Lane, Robert Launey, Wendy Lehman, Karen Lerner, Al Maysles, Kay Meehan, Arthur Schlesinger, Jean Harvey Vanderbilt, Kay Wells, and Richard Winston.

I am indebted to biographer Gerald Clarke for his magnificent books about Truman Capote and for his generosity. My thanks to Alan U. Schwartz and the Truman Capote Literary Trust; George J. Gillespie III and the Katharine Graham Estate; William Stingone, Wayne Furman, and Tom Lisanti of the New York Public Library; Phyllis Magidson of the Museum of the City of New York; Phyllis Collazo, Marilyn Cevino, and CJ Satterwhite of the New York Times; Eric Russ of Fairchild Publications; and Caroline Graham, Jay Cantor, Amy Fine Collins, Jean Palmieri, Michael Stier, Renee Zulueta, and Curt Gathje, who graciously shared his impressive knowledge of the Plaza Hotel.

At Wiley, my deepest appreciation to my extraordinary editor, Tom Miller, and his able assistant, Juliet Grames. At the Harvey Klinger Agency, my thanks to Harvey and to my dear friend Wendy Silbert. Finally, at home, where all good things happen and wishes come true every day, I am grateful to my husband, Mark Urman; my mother, Jean Gatto; and my children, Oliver and Cleo, for their love, faith, patience, and support.

Introduction

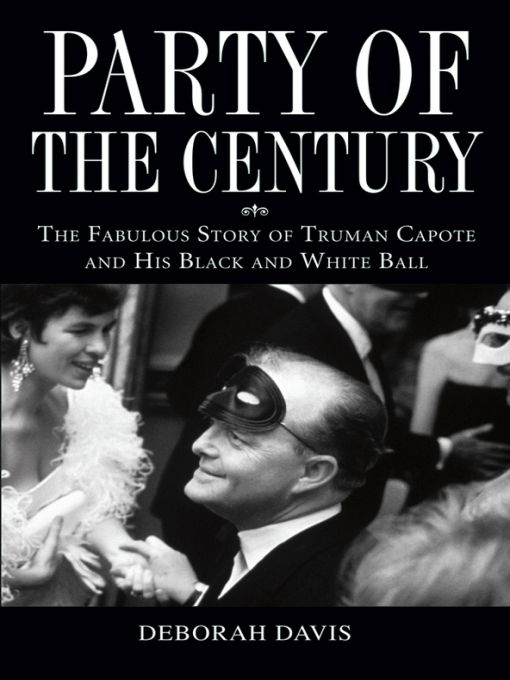

I WAS A TEENAGER IN PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND, WHEN I FIRST heard of Truman Capotes Black and White Ball. On Monday, November 28, 1966, the day of the party, I listened to a radio announcer deliver an animated account of the sudden frenzy that had taken over New York City. Capotes guests were arriving from all over the world to attend his highly anticipated masked ball at the Plaza Hotel. Limousines carried socialites and celebrities to last-minute appointments, clogging the streets. Hairdressers fashioned elaborate coiffures for hundreds of clients whose heads were filled with thoughts of the festivities to come. Designers placed finishing touches on gowns and masks that had been weeks in the making. Even though the party was still hours away and the weather was wet and punishing, spectators crowded outside the Plaza to be among the first to see the guests arrive.

I wished, Cinderella-like, for one of those coveted invitations to the ball. The night came and went, along with my fantasy. Yet the memory stayed with me until one day I asked myself the questions that transformed an adolescents reminiscence into a journalistic pursuit. How did an event hosted by a writer, as opposed to a movie star, a political leader, or a member of a royal family, command the kind of attention usually associated with premieres, inaugurations, and coronations? What compelled the gueststhe most famous, talented, and sophisticated people in the worldto throw themselves into their pre-party preparations with the enthusiasm of children getting ready for their first Halloween? And why, at the age of fourteen, did I even know about a party that was milesworldsaway, and that had not yet happened?

I learned that 1966 was the year of Truman Capote. In January, Random House had published In Cold Blood, Capotes revolutionary nonfiction novel about the murder of the Clutter family in Kansas. The extraordinary success of this book, combined with Capotes unequaled talent for self-promotion, propelled him to the front and center of the cultural scene. He was a serious writer and had been for many years, but he was also a celebrity. A bal masqu, Capote decided, would be the perfect way to celebrate his good fortune. He composed his guest list in a black-and-white school composition book, deliberating over who would be included and who would be denied entry, and he refused to reveal who was on the list and who was not. Prospective guests prayed that they would be among the chosen. The more exclusive the evening became, the more important it was to be there.

Movie stars, politicians, intellectuals, journalists, socialites, literary lions, millionaires, royalty, and even ordinary folks like Capotes doorman from the U.N. Plaza and his eleven In Cold Blood friends from Kansas were invited to rub elbows in the same place at the same time. Traditionally, Hollywood, Washington, and New York rarely intersected. Capotes party changed all that, and not just for one night.

The lucky invitees who made the cut were given seven weeks to prepare. Caught up in Capote fever, they scrambled to find appropriate outfits and perfect masks, preferably ones that were stunning or witty or made some sort of fashion statement. If they cared about making an entranceand most of them didtheir preparations had to be exhaustive.

Because of this mania, the Black and White Ball was headline news long before the first invitation went out, the first masked guest entered the Plaza, or the first photograph was snapped. Gossip columnists smelled a hot story the moment Capote announced his intention to host a masked ball for his nearest and dearest friends. In their pre-party coverage, they wrote about the guest list, the dcor, the menu, and the masks, offering insider information to all those outsiders who were not among Capotes intimates, the select 540 names on the list.

When the night finally arrived, the party was a great success. The details were reported faithfully by newspapers, magazines, and television and radio broadcasts the world over. If the Black and White Ball was famous even before it happened, it became legend in the decades that followed. Throughout the 1960s, the 70s, the 80s, and the 90s, magazines such as Vogue, Esquire, and Vanity Fair continued to run stories about this extraordinary night, searching for reasons why the event was a cultural and sociological benchmark. With every description and photograph, the partys significance increased. Pundits analyzed it, and fashion layouts celebrated it.

The ball was also a window into a bright and beckoning world. The 1960s, a decade often defined by images of Jackie Kennedys sunglasses, James Bonds martinis, Andy Warhols soup cans, and Mary Quants miniskirt, were a time of high style and high expectations. Life seemed more glamorous thensex was sexier, success more attainable. Even the moon, as the space program promised, was within reach for the very first time.

Yet many issues in this era were more serious than the rising and falling of hemlines or rockets. The war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement, womens liberation, and the unprecedented coming-of-age of seventy million teenagers, many of whom were eager for a revolution, created an atmosphere of discontent and instability. The night of the party, there was a great contrast between the glittering and carefully ordered world inside the ballroom and the simmering social and political revolution outside.