This book is dedicated to

Joan Barker

AUTHORS NOTE

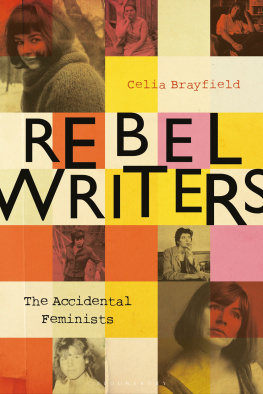

This biographical study focuses on writers whose work contributed to radical social changes more than two generations ago. They challenged many aspects of the world in which they grew up and to present their work accurately, it is also necessary to portray that world and their responses to it as they appeared at the time. Readers may be distressed by some of the events described, and the language the writers chose, particularly in Chapters 7 and 10.

Contents

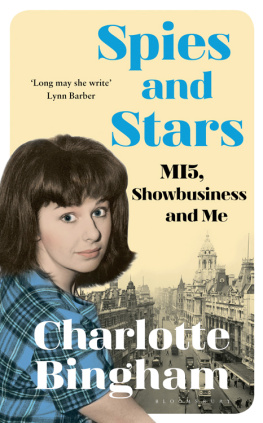

First of all, I would like to thank the Rebel Writers themselves, Lynne Reid Banks, Charlotte Bingham, Nell Dunn, Virginia Ironside and Edna OBrien for their help with this study, whether it was with patiently answered questions, kindly given permissions or, as with Charlotte and Virginia, generous amounts of time spent in delightful conversation. I would also like to thank Caitlin Davies for allowing me to consult archive material relating to her mother, Margaret Forster, and the literary agents Caroline Michel and Rachel Calder for handling my queries.

I am most grateful to the librarians archivists who helped me identify and consult the valuable resources in their charge, including Greg Buzzwell at the British Library, Kathy Shoemaker, Reference co-ordinator for the Stuart A Rose Manuscript Archives at Emory University in Georgia, USA; Eugene Roche at the James Joyce Library at University College Dublin; Danni Caulfield and Ceri Lumley at the Special Collections at the University of Reading; Kirby Smith at the Penguin Random House UK Archives in Rushden, Northamptonshire; Sam Maddra at the University of Glasgow where the MacGibbon & Kee files are; Matthew Geoghegan at the Irish Film Classification Office, which holds the records of the Censorship of Publications Board, and the great team at the Bodleian Library in Oxford. As ever, I am thankful for the encouragement and support of my agent, Jonathan Lloyd and the intrepid team of Curtis Brown.

In addition, Im indebted to two assiduous researchers, Nathan Blansett in Atlanta, Georgia who searched Edna OBriens papers for me and Daphne Power in London who helped with press coverage and picture research.

The help, in cash and kind, of Bath Spa University enabled me to extend my research much further than I would have otherwise been able to do, and also to carry out the substantial initial research needed to prepare this book as a proposal. I am particularly grateful to my colleagues Mark Loon, Richard Kerridge, Paul Meyer and Professor John Strachan and Katie Rickard for their support and to Professor Phil Tew of Brunel University London for his wise advice.

After developing the idea for this book over five years, it was a wonderful moment when Tatiana Wilde at I.B.Tauris responded so positively to my proposal and seemed to love the idea as much as I did. Im deeply appreciative of her enthusiasm and also of her care and thoroughness in editing the manuscript. When Bloomsbury Publishing took over the project I was thrilled with the flair and energy with which Jayne Parsons, non-fiction publishing director, moved the process to completion. I am also most grateful for expertise and vision of Jude Drake in publicising the book. My thanks are also due to our managing editor, Claire Browne, for her masterful command of the books creation.

In working on a book about writers, it has been marvellous to have the encouragement of so many fellow writers and bookish friends. I am particularly grateful for Helen Rappaport for her astute historians eye and kind advice, and to Julia Bell, Amanda Craig, Deborah Levy, Tanya Bruce-Lockhart, Daisy Parente, Professor Dame Marina Warner and Professor Fay Weldon among many others, for cheering me on. Chloe Brayfield has contributed her 20-20 judgment on many occasions, read endless drafts and inspired many a light-bulb moment. Finally, I am grateful for Joan Barker for her friendship and companionship along the way.

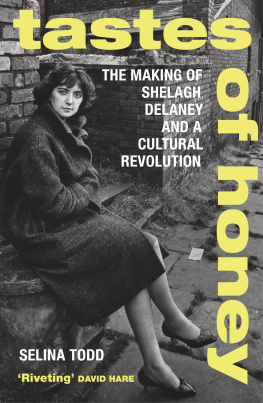

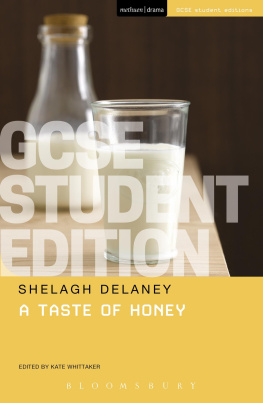

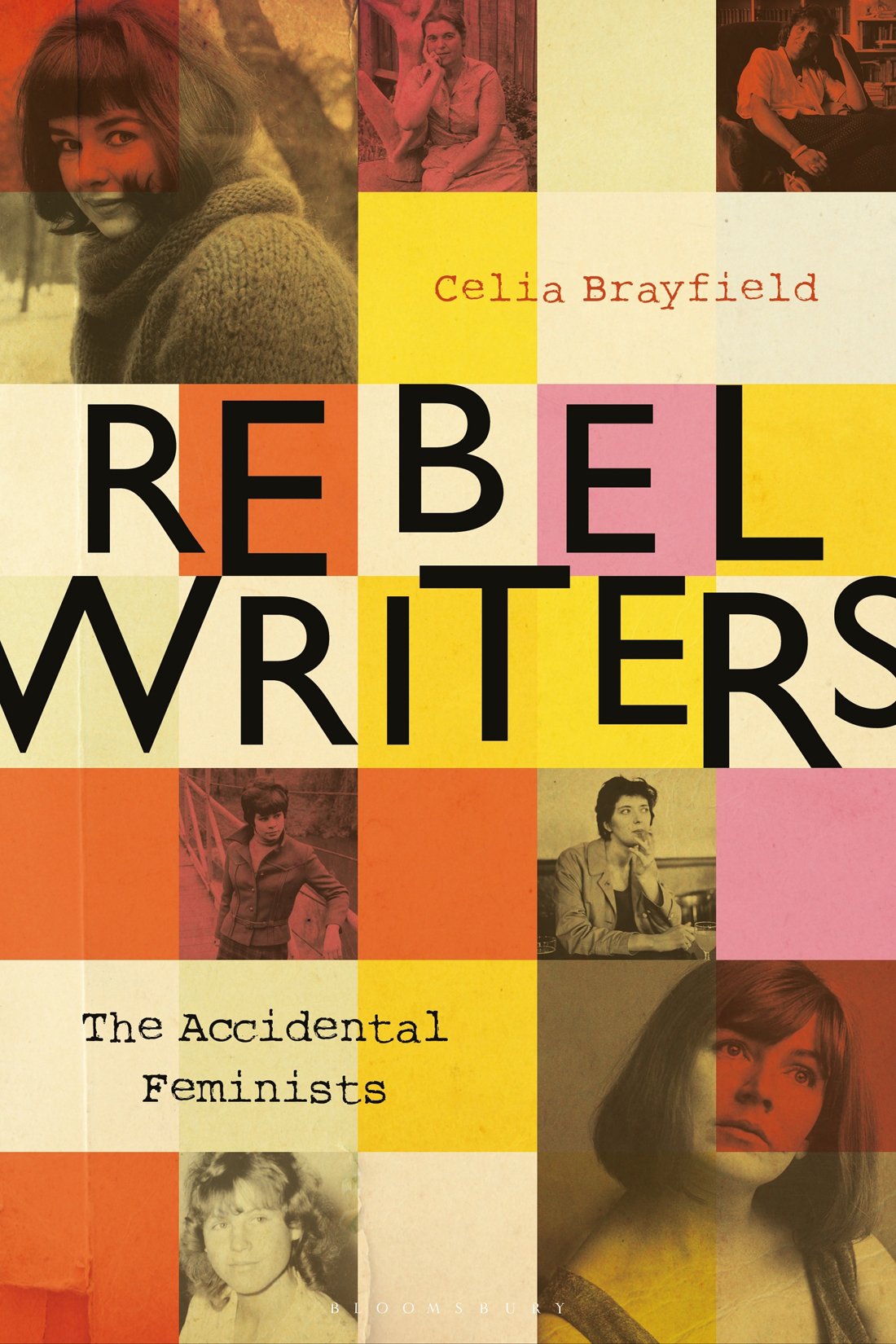

In London in 1958 a play written by a 19-year-old redefined womens writing in Britain. It also began a movement that would change womens lives. The play was A Taste of Honey and the author, Shelagh Delaney, was the first of a succession of very young women who wrote about their lives with an honesty that dazzled the world. Some of their work is shocking, even today, because much about their lives was shocking in reality. They rebelled against sexism, inequality and prejudice and in doing so also rejected masculine definitions of what writing and a writer should be. After Delaney came Edna OBrien, Lynne Reid Banks, Charlotte Bingham, Nell Dunn, Virginia Ironside and Margaret Forster to challenge traditional concepts of womanhood in their novels, films, television, essays and journalism.

Not since the Bronts had a group of writers been united by such a burning need to tell the truth about what it was like to be a girl. These authors were astonishingly young, some still teenagers when they started to write. Equally astonishing is that they wrote about the same things but could hardly have come from more different backgrounds. The pampered daughter of a multi-millionaire had the same yearning for a different way of life as a girl from a rat-infested Northern slum. A high-achieving Oxford graduate and a failed actress shared the same sense of being motherless and resolved to find a better way of creating a family. An ex-debutante and a sophisticated art student felt the same feeling of abandonment as they drifted from party to party, wondering what love might be while fighting off predatory males. Their characters all feel the instinct to revolt against their destiny as the narrator of Nell Dunns Poor Cow,

There are many connections between these women but founding a literary movement was the last thing on their minds, which makes it all the more remarkable that they spoke with one voice. They shared an inner place, the territory of girlhood, rather than such traditional literary landscapes as Paris cafs or Oxford common rooms. Their work is full of joy and humour but is not afraid to confront the darker aspects of their lives, the violence, tragedy and injustice they experienced. And it is constructive, in that their characters are all looking for better ways to live, all proposing new roles for women, new family structures, new ways to express love.

These writers did not create a literary movement consciously. They were isolated young women who shared values and perceptions but lacked the self-regard to see themselves as cultural crusaders. Nor was that role bestowed on them by the media, as it was on their contemporaries, the Angry Young Men, although this book argues that their work was far more influential. They were beneficiaries of a genre created by the publishing industry which gave them platforms without understanding quite how subversive their work would prove to be. It is delicious to reflect that the men who thought they were merely exploiting a passing trend in publishing were unknowingly laying the foundations of second-wave feminism.

There were some links between the Rebel Writers. The two youngest of this group, Charlotte Bingham and Virginia Ironside, had lived in the same area of London, on the edge of Chelsea since childhood. Some formed relationships after their start of their writing careers. Edna OBrien and Nell Dunn moved into the same street in a riverside inner-suburb of London and sat out in their gardens on summer evenings talking about writing. They became friends and were still meeting for lunch, sometimes with Margaret Drabble, at the time this book was written. So something of the shape of a traditional literary movement can be made out in this story, although the Rebel Writers never met together over years to share their writing and define a creative stance as did The Inklings in pre-war Oxford or the Beat Generation in 1950s America