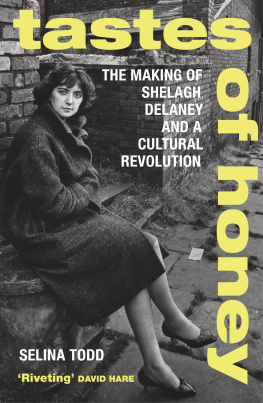

ALSO BY SELINA TODD

The People: The Rise and Fall of the Working Class

19102010

Young Women, Work and Family in England

19181950

Selina Todd

TASTES OF HONEY

The Making of Shelagh Delaney and a Cultural Revolution

VINTAGE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Vintage in 2021

First published in hardback by Chatto & Windus in 2019

Copyright Selina Todd 2019

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover photograph Arnold Newman/Getty Images

ISBN: 978-1-473-54509-0

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

For Charlotte Delaney

and Senia Paseta

1

Curtain Up

In April 1958, nineteen-year-old Sheila Delaney, the daughter of a Salford bus driver, sent a manuscript to Joan Littlewood, the director of Londons avant-garde Theatre Workshop. Her covering note explained to Miss Littlewood that this bundle of thin, closely typed sheets of paper was her first play A Taste of Honey. A fortnight ago I didnt know the theatre existed, she claimed. But then, a young man, anxious to improve my mind, took me to the Opera House in Manchester and I came away after the performance having suddenly realized that at last, after nineteen years of life, I had discovered something that meant more to me than myself. The next day she borrowed an unbelievable typewriter and set to and produced this little epic dont ask me why Im quite unqualified for anything like this.

The story Sheila Delaney told to Joan Littlewood was only partly true her letter was a typically shrewd attempt to appeal to her audience, in this case by presenting herself as a naive, northern ingnue. Even her signature was embellished. She called herself Shelagh Delaney the name she will be known by for the rest of this book in a deliberate rejection of the identity of plain Sheila from Salford and the future laid out for her. Shelagh Delaney was a young woman ambitious to escape the life shed been born into. But she was also determined to tell the stories of the women she left behind. A Taste of Honey was her first attempt, and arguably her best. Shelaghs play focuses on Jo, a working-class teenager who lives in Salford with her single mother, Helen, and who becomes a single mother herself as the result of a brief affair with a black sailor. Jo rages against her fate, but finds solace in her friendship with Geof, a gay art student, who is keen to make a home for her and the baby. The play ends when Helen returns from a brief, failed marriage to find Jos labour pains beginning.

A Taste of Honey grabbed Joan Littlewoods attention. Working-class people, if they appeared at all in books, films or plays in the fifties, were as the Listener magazine said comic or loyal, or more frequently both.

This situation was slowly changing. John Osbornes play Look Back in Anger, staged at the Royal Court in London in 1956, was the ripple that quickly turned into a new wave of novels, plays and films about a restless generation of young working-class upstarts. But the protagonists who wanted adventure Joe Lampton in John Braines novel Room at the Top (1957), or Arthur Seaton in Alan Sillitoes Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1958) were men. Women often held them back. One kiss and they were envisaging marriage; pregnancy turned them into dutiful replicas of their mothers. Their biology determined they could do nothing else.

Shelagh Delaney was the first post-war playwright to suggest that these women had minds and desires of their own, a radical proposal in the fifties. Motherhood is supposed to come natural to women, says Geof, voicing the standard medical opinion of the time pregnancy was meant to render women docile, maternity to fulfil them. Advertisers, educators, policymakers and psychologists told women that they were luckier than their mothers the post-war welfare state, and affluence brought about by full employment, rendered their lives both easier and more fulfilling. Clad in New Look dresses they could spend their lives making happy homes for their hard-working husbands and their healthy children the citizens of Britains brave new future. But this was a life that Shelagh showed was beyond thousands of women who, like Jo and Helen, continued to live in overcrowded slums. Even more radically, she suggested it was a life that they did not want. More than a decade before the Womens Liberation Movement emerged in Britain, Shelagh Delaney created characters who challenged the assumption that women found fulfilment in marriage and motherhood. Neither Jo nor Helen is satisfied by being a wife or mother. For Helen, motherhood and marriage present at least as many burdens as joys. Jo, meanwhile, rages against her body and her fate. In a world that told working-class women they should be grateful for anything they got, Jo and Helen openly longed for a taste of honey, craving love, creativity, adventure and escape.

In a telegram to her new protge, Joan Littlewood announced that her company would stage A Taste of Honey as their next production at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East. Shelagh was present for the premiere on 27 May 1958. Theatre Workshop had a reputation for courting controversy, but neither Joan nor Gerry Raffles, her theatre manager, had any idea how Shelaghs play would be received. Raffles warned Frances Cuka and Murray Melvin the actors playing Jo and Geof to be ready to run from the stage if the audience turned abusive when they took their curtain call.

When the curtain fell on that Tuesday evening, there was a moments stunned silence and then the audience roared their approval. Within days Honey was a hit and Shelagh the most famous teenager in Britain. Over the next three weeks, hundreds of people flocked to Stratford East to watch an extraordinary episode in British theatre history. A story of slums, sexual politics and race relations, A Taste of Honey caught Britain on the cusp of change. At a time when Conservative Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was claiming people had never had it so good, reactions to the play exposed a deep social chasm. Almost all the press condemned Honey as tasteless muck. Even those reviewers who enjoyed it betrayed their amazement that such apparently moronic people can be so moving, as Denis Constanduros, sent from the BBC drama department to see what all the fuss was about, put it.

Honey turned Shelagh into a celebrity. The burning question posed by journalists, fans and most of the arts establishment was how a working-class teenage girl from Salford could write such a shattering play. For Shelagh came from the place she wrote about, much to the horror and prurient fascination of her critics. The Spectator