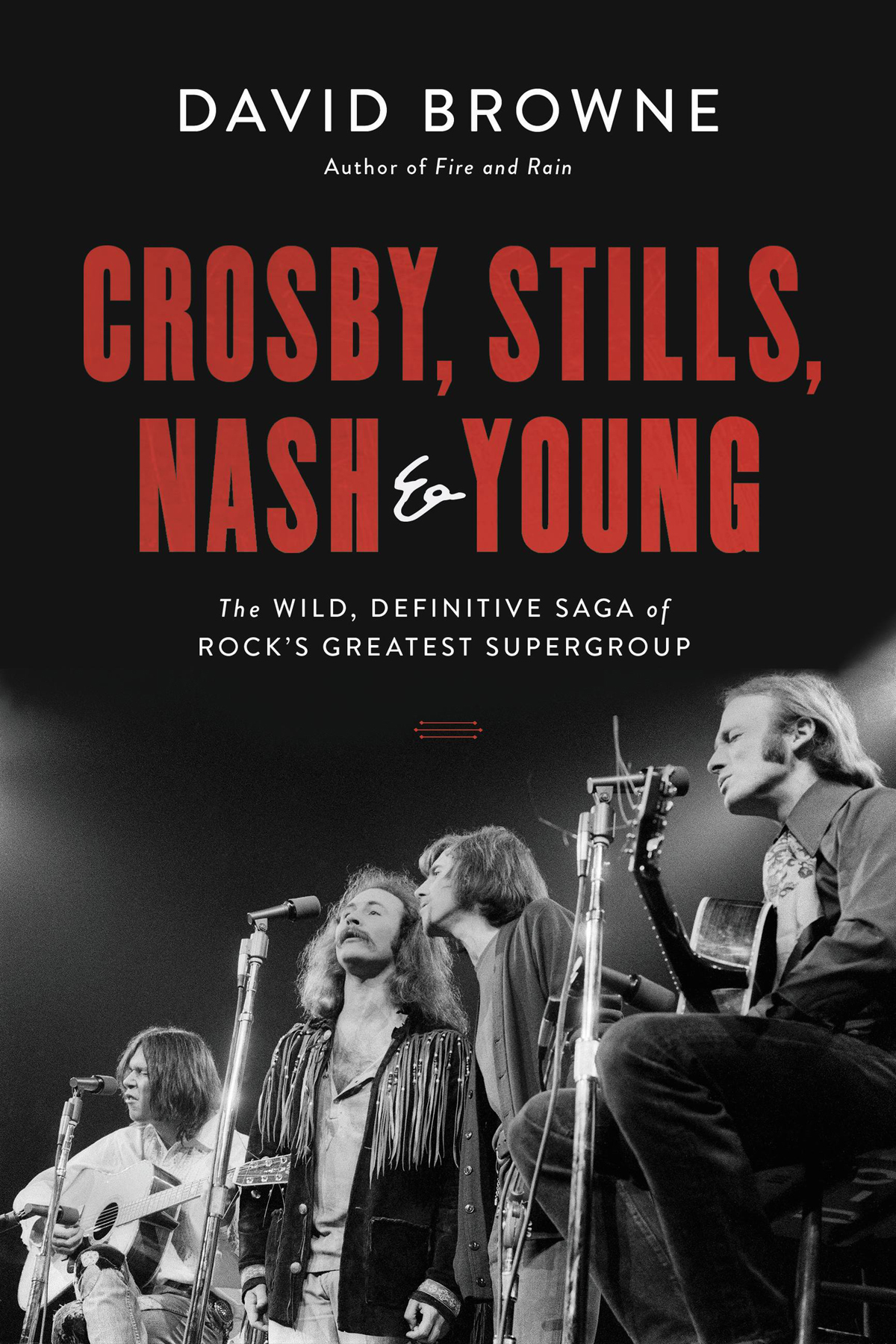

Copyright 2019 by David Browne

Cover design by Kerry Rubenstein

Cover image Ray Stevenson

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright.

The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Da Capo Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

dacapopress.com

@DaCapoPress, @DaCapoPR

First Edition: August 2019

Published by Da Capo Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Da Capo Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Editorial production by Christine Marra, Marrathon Production Services.

www.marrathoneditorial.org

Book design by Jane Raese

Set in 10-point Century ITC

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-0-306-90328-1 (hardcover), ISBN 978-0-306-92264-0 (ebook)

E3-20190213-JV-NF-ORI

So Many Roads: The Life and Times of the Grateful Dead

Fire and Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY, and the Lost Story of 1970

Dream Brother: The Lives and Music of Jeff and Tim Buckley

Goodbye 20th Century: A Biography of Sonic Youth

Amped: How Big Air, Big Dollars, and a New Generation Took Sports to the Extreme

The Spirit of 76: From Politics to Technology, the Year America Went Rock & Roll

To my father, Cliff, my mother, Raymonde, and my sister Linda Virginia, who were all with us when I discovered this music and who bought some of these records for me. I always think of you when I hear this music, and you are all deeply missed.

What a story, Graham Nash said to me, shaking his head, during an interview for this book. What a fucked-up foursome. It was late 2017, and at that moment, Crosby, Stills and Nashand sometimes Youngappeared to be shattered for good, the result of beefs and grievances that had been festering for years and had finally discharged. Even after nearly five decades of upheaval, you could only shake your own head at the disarray of it all.

But way back in more innocent times, it was the voices, not the drama, we noticed. On a family drive sometime in the early 70s, I can still recall turning on the AM radio on the dashboard and the inside of the car unexpectedly being engulfed in massive, densely packed harmonies, the lyrics saying something about returning to some sort of garden. Instantly drawn to the sound, I reached forward from the back seat to pump up the volume dial, probably to my parents annoyance. Afterward, the DJ informed us we had just heard a group called Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young.

As one of those kids who often walked around with a transistor radio and its white, one-ear bud, I must have heard some of the records each of them had been a part of before: the Byrds Mr. Tambourine Man or Turn! Turn! Turn!; the Hollies Bus Stop; Buffalo Springfields For What Its Worth. Id probably chanced upon Crosby, Stills and Nashs Marrakesh Express or the shortened version of Suite: Judy Blue Eyes on New Yorks biggest AM station. All I knew was that, from the singing to the grinding organ to the jabbing guitar solo midway through, Id never heard anything quite like Woodstock before. It made everything outside the window, especially the dreary car dealership on Route 35 in New Jersey where my mother worked, seem somehow more upliftingan early power-of-song moment.

Not long after, thanks to birthday-gift money and whatever allowance I could scrounge up in my entering-teen days, I joined the millions of people who had already bought copies of the evolving groups first two LPs, Crosby, Stills & Nash and Dj vu. The covers reflected their different moods. On the former, three guys, dressed hippie-casual in denim and boots and lounging on a tattered couch, stared directly at the camera; they looked like more charismatic versions of my friends older brothers. On the latter album, those three were joined by three more peopleand a dogin a duskier, Old West setting, none of them looking happy. Using the songwriting credits as my guide, I was struck by the way David Crosby, Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young each sang in a distinctive voice and had a songwriting style his own, yet still managed to create a unified sound together. The lyrics had an unguarded directness I wasnt accustomed to hearing in much rock at the time. Getting into Bob Dylans head on his records was a challenge, as was discerning his intention; with these people, their feelings of confusion, romantic anguish or anger were entirely out in the open. You never forget how eerily chill and singular a song like Guinnevere sounded or how Youngs voice on Helpless was so fragile, high and spooky.

I read what I could on them at the time, mostly in magazines like Rolling Stone and its scrappier music competitors Creem, Circus and Hit Parader. I learned that the group featured members of Buffalo Springfield, the Byrds and the Hollies. Some writers called them a supergroup, whatever that was. They were ubiquitous and mythological, and I also learned they were already defunct.

I spent the next few years buying everything else of theirs I could find. It was like entering the world of an extended musical family but with siblings who were all from different clans. How could the person who made a rattled and jittery record like Youngs Time Fades Away be in the same band with the guy who made Nashs far more crafted and precise Songs for Beginners? How could both harmonize with a guy like Stills, whose force-of-nature voice and musicianship almost swallowed up albums like Stephen Stills? And how could any of them bond with the indolently blissed-out hippie at the center of Crosbys If I Could Only Remember My Name? This was a band?

Well, it was and it wasnt, as many of us came to realize. Id read in 1974 that they were playing together again. To my eternal regret, I didnt go to the concert; my parents frowned on me venturing to nearby Jersey City, warning it was an awful place. Once that tour was over, we all awaited a new album from thembut it never came. Instead they went back to their separate worlds. I first saw them onstage in 1977, when Crosby, Stills and Nash, no Young, reformed for an album and tour. Even in the nosebleed seats where my friend Chris and I sat, it was pretty thrilling to behold them in person and watch Stills run around the parameters of the stage by way of a wireless guitar. (How did he do that, we thought?) But a year later theyd shattered again. And so it went: they would reform as a trio or a quartet (Young generally seemed to keep as much distance as possible), resurrect their songs and vocal interplay, make more money than most of us would in a lifetime, then burst into pieces and go about their own business before starting up the cycle again. One of their former employees told me theyd broken up eight times during his tenure with them.