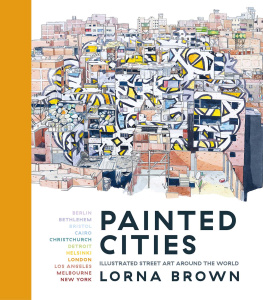

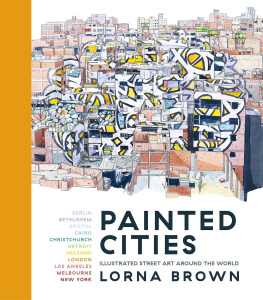

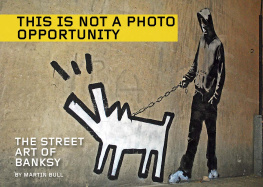

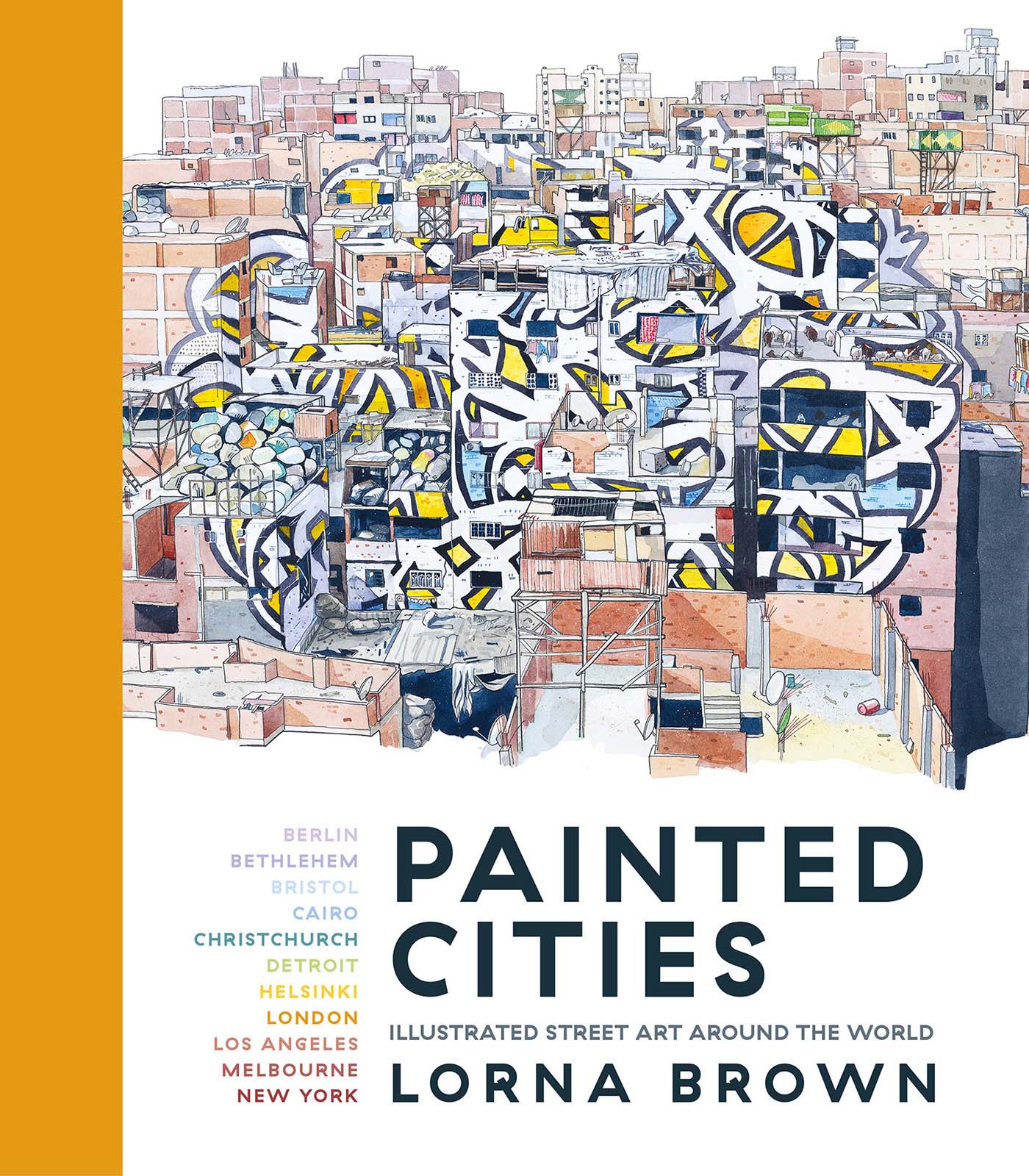

PAINTED CITIES

ILLUSTRATED STREET ART AROUND THE WORLD

Lorna Brown

www.readanima.com

Lorna Brown has travelled the world to produce this collection of paintings of street art in urban landscapes. Visiting London, Bristol, Helsinki, Berlin, Cairo, Bethlehem, New York, Los Angeles, Detroit, Christchurch and Melbourne, Painted Cities demonstrates how the architecture, either physical or social, shapes the unique street art in each city.

CONTENTS

I never intended to create a book about street art. Through painting buildings and architecture, street art had become an incidental motif within my work. The buildings I was drawn to and found visually appealing were the dusty ones, the dilapidated ones, the tired ones the exact same buildings in the same parts of town that welcomed the street artists. Yet, by replicating the street art on my version of painted walls, something strange and new happened: the art and the place became unified through the watercolour washes. No longer paint on brick, but the representation of paint on brick through paint on paint.

Whenever I had seen photos of street art and graffiti in the past, they were so often cropped in tightly, placing all the emphasis on the art or writing itself, yet simultaneously missing what made the work different from paint on canvas. They were lacking context and environment a critical part of the story.

And so began my slow exploration of this context, through eleven cities around the world. I noticed the universal elements that tied painting on walls together, as well as identified some of the place-specific influences that directed the work. I gained a respect and understanding of graffiti writing over the months, even though it had been brightly coloured murals that gained my attention in the beginning.

Each trip to a new city would involve walking, skating or biking around, camera in hand, shooting reference photos and absorbing the place. I would talk to locals and go on art tours, drive around with graffiti writers and hear stories of each city. Occasionally, I would head out on a quest to find a specific piece, like a treasure hunt. Sometimes I would find what I was looking for, and sometimes I would not.

I had intended to include Belfast in this book, but life had other plans. My bag, containing most of my possessions, all of my handwritten research, my passport, vast quantities of reference photographs and all my essays, was stolen on the way to the airport to fly there. Belfast would have to take a back seat as I began the process of piecing the project back together from scraps.

I would then hole up somewhere in the world to paint from the reference I had gathered. For a while this was my studio in London, but the need to extract myself from life to finish the project dropped me in Malmo, Sweden where I painted, reflected, wrote and skated.

Henri Cartier-Bresson said, Photography is an immediate reaction, drawing is a meditation. My painting encapsulates both of these concepts. The collection of reference photography froze the moment in the life of the wall; the works that sat on it at that time and on that day; the state of decay of the building and how many windows were smashed. Then the slow process of construction lines, perspective grids, inking and painting allowed my mind to sit inside that moment for hours, meditating on its significance, holding on to it every corner explored with my eyes.

They say that the more you know about something, the more you know you dont know. This book is a collection of moments and meditations on these places, yet at the end of this set of travels I realized that I had barely scratched the surface and could probably spend a lifetime visiting a thousand cities to hear a thousand stories. This is, therefore, just the beginning. It is in no way comprehensive, but the first tentative step in trying to understand the world a little better by looking at the writing on the wall.

BETHLEHEM

PALESTINE

It all began in Palestine, in a small village outside of the city of Nablus, where I was volunteering for the skateboarding charity SkatePal in 2016. For the weeks I was living there, I used all my time outside of teaching the children how to skateboard, to travel around and experience as much of this unique place as possible. The buildings and structures of the occupation held particular interest for me: the concrete blocks surrounding bus stops, put in place to deter car-ramming attacks on Israeli settlers; watchtowers along all the major roads containing heavily armed soldiers of the Israel Defence Forces; tall wire fences surrounded Israeli settlement areas and, perhaps most famous of all, was the wall.

The separation wall was an imposing feature that cleaved the land in two. It stood nearly 8 metres (2.25 ft) high at points, constructed of solid concrete, and cast long shadows on to the land. Preventing free movement between the West Bank and Israel, the construction of the wall began after the Second Intifada of 2000, as a security measure following the subsequent wave of violence. It used the demarcation line known as the Green Line, drawn up in 1949 between Israel and its neighbours, as a guide. The Green Line was never intended to be an international boundary, which made the route the wall followed a complicated and controversial one. A 2009 report by the United Nations noted that the route the wall took annexed a total of 9.5 per cent of Palestinian land to the Israeli side. Separating farmers from their land, towns from their wells, and splitting communities, it has been condemned by the United Nations.

It was no surprise that, at points along the wall throughout Palestine, artists had been using it as a canvas to express themselves, to repurpose and subvert it, to retake ownership of the environment. I visited the wall at several points Tulkarm in the north; the enclave of Qalqilya where the wall wraps almost completely around the city leaving just a narrow entry point; and Bethlehem, located to the south of Jerusalem.

Of all the locations, it was Bethlehem where the drips of graffiti had turned into a tsunami. Street artists from around the world had travelled to the wall to paint artists whose work I would see in other cities on my journey following the story of painted cities: How and Nosm, Lushsux and, most famously of all, Banksy.

From my many conversations with Palestinians living in the West Bank, the predominant message was one of wanting to be heard by the world beyond the wall. There was a strong feeling of isolation, of being forgotten and ignored. Powerless. The internationally renowned artists choosing to shine a spotlight on the wall and the politics of the area, bringing the eyes of the world upon this place, had the ability to address this. The juxtaposition of world-famous works butting up next to the work of local artists, in addition to the messages left by visiting tourists, is striking part this is my story and part we hear you.

When I visited, it was estimated that street art tourism brought in more tourists than religious tourism to the city of Bethlehem. It was a tangible way in which the writing on the wall had given practical help to a community that had suffered under the image of it being too dangerous a place to visit. Multiple Official Banksy shops were sprinkled around, created by entrepreneurial locals. As we walked the streets, a young Palestinian boy was chasing and yelling at another boy, waving a broom in the air above his head as he did so. It turned out that the one being chased had burst all of the balloons outside of his Official Banksy shop. As we stepped inside, the young boy with the broom came back in to his tiny space, greeted us with a smile and gave us some biscuits. There was an original Banksy piece sprayed on the wall and protected with a sheet of Perspex, the shop erected around it selling snacks and drinks but also postcards and magnets featuring the more famous street art pieces of the city. I talked to him for a while, a little in Arabic and a little in English, bought a magnet and some postcards and left him to replacing the balloons.