Also by Ben Wilson

Metropolis: A History of the City, Humankinds Greatest Invention

Heyday: The 1850s and the Dawn of the Global Age

Empire of the Deep: The Rise and Fall of the British Navy

What Price Liberty?: How Freedom Was Won and Is Being Lost

Decency & Disorder: The Age of Cant, 17891837

The Laughter of Triumph: William Hone and the Fight for the Free Press

Copyright 2023 by Ben Wilson

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto. Simultaneously published in hardcover in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape, an imprint of Vintage, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London. This edition published by arrangement with Jonathan Cape, a division of Penguin Random House Ltd., London.

www.doubleday.com

Doubleday and the portrayal of an anchor with a dolphin are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

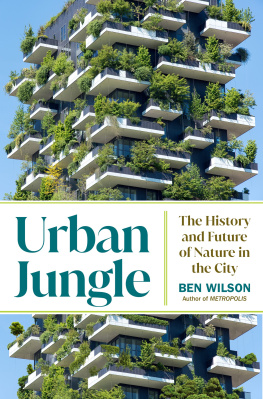

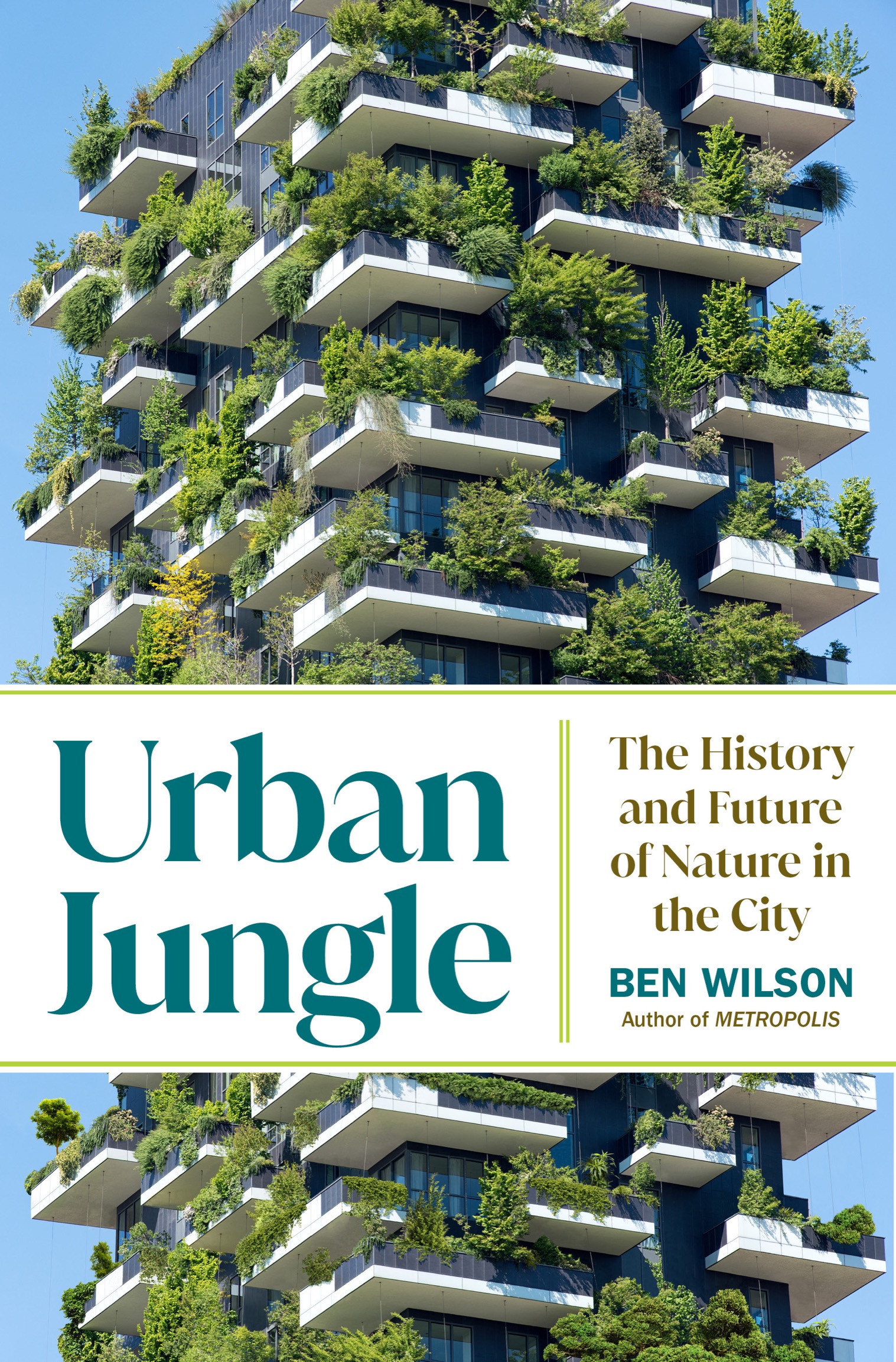

Cover photograph: The Milan Vertical Forest, 20072014, Milan, Italy by Boeri Studio. Typology: Architecture, Vertical forest. Design team: Stefano Boeri (founding partner); (executive architects) Davor Popovic, Francesco de Felice; (project architects) Phase 1Urban planning and preliminary project: Frederic de Smet (coordination), Daniele Barillari, Julien Boatyard, Matilde Cassani, Andrea Casetto, Francesca Cesa Bianchi, Inge Lengwenus, Corrado Longa, Eleanna Kotsikou, Matteo Marzi, Emanuela Messina, Andrea Sellanes. Phase 2Detail project: Gianni Bertoldi (coordination), Alessandro Agosti, Marco Brega, Andrea Casetto, Matteo Colognese, Angela Parrozzani, Stefano Onnis. Consultants: Arup Italia s.r.l. (structural engineering); Deerns Italia S.p.A. (facilities design); Tekne s.p.a. (detailed design); LAND s.r.l. (open space design); Alpina S.p.A. (infrastructure design); MI.PR.AV. s.r.l. (contract administration [DL]); Studio Emanuela Borio and Laura Gatti (landscape design)

Cover photograph by Andrea/EyeEm

Cover design by John Fontana

Library of Congress Control Number: 2022950934

ISBN9780385548113

Ebook ISBN9780385548120

a_prh_6.0_142818108_c0_r0

Contents

_142818108_

List of Illustrations

>, via Wikimedia Commons)

George Cruikshank, London going out of Town or The March of Bricks and Mortar, 1829. (Authors collection)

The Mughal Emperor Babur receives the envoys Uzbeg and Rauput in the garden at Agra, 18 December 1528. (Bridgeman Images)

A couple examining wildflowers growing on a bombsite in Gresham Street in the City of London in July 1943. (Popperfoto / Getty Images)

Protest against further development of the banks of the Spree River in Kreuzberg. (Bjrn Kietzmann / ImageBROKER / Alamy Stock Photo)

)

)

A crop of marijuana is cut down by sanitation workers in the shadow of Brooklyn Federal Building, New York City, 1951. (Brooklyn Daily Eagle photographs, Brooklyn Public Library, Center for Brooklyn History)

>, via Wikimedia Commons)

Ashrama Gardens, Bangalore. (Nataraja Upadhya)

Marsh grass high around the broken porch of a home destroyed by Superstorm Sandy, 2013. (REUTERS / Alamy Stock Photo)

Hunters Point South Wetlands, New York City. (NYC Economic Development Corporation)

Jardins potagers near le pont Mirabeau, Paris, 1918. (Auguste Lon, Muse Albert Kahn)

Otters, Singapore, 2022. (Suhaimi Abdullah / NurPhoto via Getty Images)

)

Introduction

Their thick roots twist around masonry in a mesmerising, tangled mass that is at once beautiful and terrifying. They smash roads and rip through concrete. Mighty banyans are the slayers of cities. Their seeds, carried on the wind or dropped by birds, settle in tiny crevices in the structures built by humans. The roots push outwards and downwards seeking nutrients, enveloping the stone, concrete or asphalt in a mesh until they can exploit a crack in which to find sustenance. Banyans are perfectly suited to the dry, hard, urban environment. There is no barrier they cant overcome. They clamp defenceless walls and buildings with roots coiling like the tentacles of a mythic sea monster, strangling its prey in a crushing embrace of death.

What chance does a city have against such power? The site of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, with its helpless temples in the talons of the banyan, reveals what happens when they run amok.

Yet banyans, for all their city-shredding potential, are a quintessential urban tree across south-east Asia. Guangzhou has an astonishing 276,200. Walk along Forbes Street in Hong Kong and you can see the majestic power of banyan trees as twenty-two grip on to a section of wall, their canopies shading the street below. No one planted them, but they thrive here nonetheless. Like any true urbanite, they can adapt to a hostile environment. Hong Kongs Tree Professor Jim Chi-yung has counted 1,275 epiphytes tropical trees that can begin life on almost any surface growing against the odds out of 505 humanmade structures in the city. The most common is Ficus microcarpa, the Chinese banyan, and some specimens have grown to twenty metres. They do not occupy significant ground space, he explains, and grow spontaneously with little human intervention or carethey present a special habitat with a rich complement of flora, adding significantly to the otherwise treeless streetscape.

Hong Kong is known for its skyscrapers and density; but look at it another way, and it is a city of gravity-defying banyans, natures skyscrapers, a hanging forest that amalgamates human culture and wild nature. The Forbes Street banyans recall an ancient form of Asian urbanism. Trees such as the banyan found a place in the cityscape, despite their enormous size and destructive powers, because they were sacred. They also offered environmental services, being providers of cooling shade. When Europeans reached the Indian Ocean, the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea in the wake of Portuguese colonial expansion from the late fifteenth century CE, they encountered cities quite unlike the compact, tree-starved metropolises of Europe. A French Jesuit described the great Sumatran port city of Aceh in the seventeenth century: Imagine a forest of coconut trees, bamboos, pineapples and bananasput into this forest an incredible number of housesdivide [the] various quarters by meadows and woods; spread throughout this forest as many people as you see in your towns, when they are well populated; [and] you will form a pretty accurate idea of AcehEverything is neglected and natural, rustic and even a little wild. When one is at anchor one sees not a single vestige or appearance of a city, because the great trees along the shore hide all its houses.

Neglected, natural, rustic and wild: this is city and nature entwined in ways we have been trained to overlook or disregard. This ruralopolis might have been characteristic of the tropics and Mesoamerica, but in cities in almost all latitudes, the veneer of civilisation is paper-thin. Scratch at the carapace and you discover a world teeming with wildlife.

In writing Urban Jungle, I set myself the task of exploring the wild side of cities the parts of urban life that long fell outside the purview of the historian: the middens and rubbish dumps, the abandoned sites and empty rooftops, the strips of land behind chain-link fences and alongside railway lines. For much of history, wild patches in cities, with their diverse flora and fauna, provided food for the pot, fuel for the fire, ingredients for medicines, and places for play and recreation. The dividing line between city and countryside was blurry. Only comparatively recently did we break from those traditions.