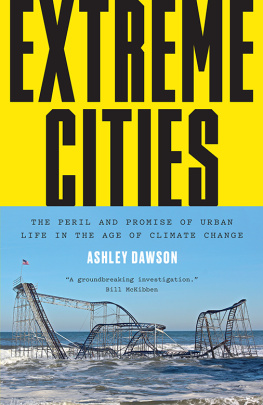

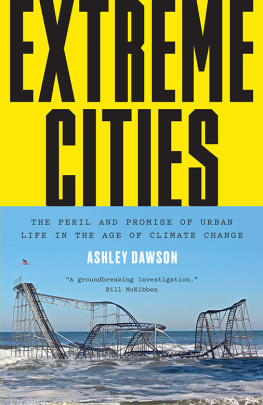

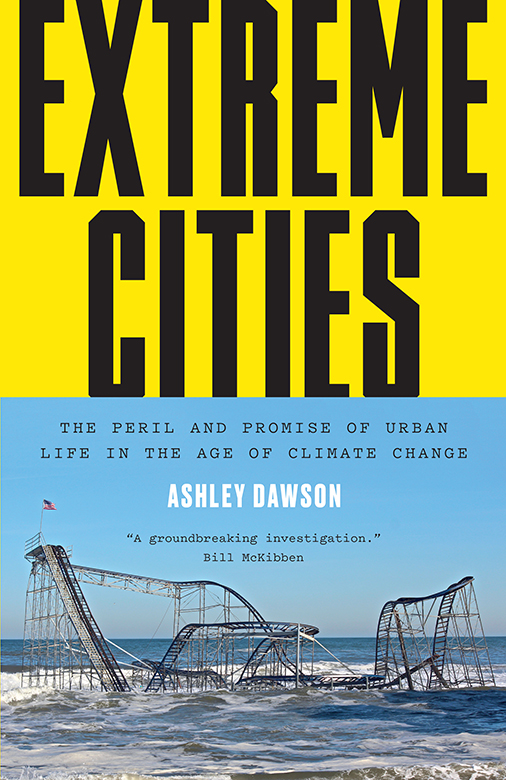

Extreme Cities

The Peril and Promise of Urban Life

in the Age of Climate Change

Ashley Dawson

This eBook is licensed to adam katzman, adamlkatzman@gmail.com on 11/27/2018

First published by Verso 2017

Ashley Dawson 2017

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-036-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-038-8 (UK EBK)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78478-037-1 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

Typeset in Sabon LT by Hewer Text UK Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed in the US by Maple Press

This eBook is licensed to adam katzman, adamlkatzman@gmail.com on 11/27/2018

Contents

This eBook is licensed to adam katzman, adamlkatzman@gmail.com on 11/27/2018

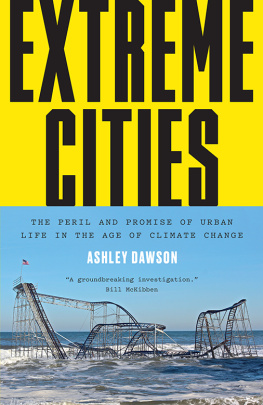

Jetstar Rollercoaster in Seaside Heights, New Jersey, after Hurricane Sandy. Photo by Hypnotica Studios Infinite, 2012.

I found a huge blister of water forming on my bedroom wall when the wind woke me in the middle of the night. Hurricane Sandy had been buffeting the city all day, and as nightfall approached I hunkered down in my apartment in Jackson Heights, Queens, hoping that my neighborhoods elevation would bring a degree of safety. The previous day New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg had ordered the evacuation of everyone living in flood Zone A, a total of 375,000 people, and by evening the city halted all subway service, marooning people without cars in their neighborhoods. There was little to do the following day, Monday, 29 October, other than to fill the bathtub with water, stock up on batteries, and watch the sky over the city ominously darken. When the full force of the storm hit that night, the intensifying winds drove rain into the bricks and mortar of my building, which age had rendered all too permeable to such a sustained onslaught, producing a threatening bulge in the paint of my bedroom wall. I prodded the blister gingerly and mopped, slept fitfully, and then was awoken by the winds raging outside to find the blister growing larger again, in what seemed like an endless cycle. By morning, I felt exhausted but fortunate to have escaped the hurricane relatively lightly. We still had power, and taxis and delivery trucks rolled through the streets.

But other portions of the city had sustained major damage. The superstorm drove a wall of water into the financial district of Manhattan, capitalisms great citadel. Sandys fourteen-foot surge had flooded a power substation in Manhattans Lower East Side, causing a catastrophic short circuit that cut off electricity to all of Lower Manhattan. The surge had also inundated many low-lying areas: Red Hook, the Navy Yard, Brighton Beach, and Coney Island in Brooklyn; areas around Jamaica Bay in Queens, including the Rockaways, a barrier island where the community of Breezy Point was utterly destroyed by a fire started by short-circuiting electrical equipment. On Staten Island, a borough still mourning losses from 9/11, beachside communities like Ocean Breeze and Oakwood Beach had flooded catastrophically.

In the days following Sandys landfall, it became clear that it had been one of the most destructive storms ever to hit the United States. The storm killed 160 people in the New York metropolitan region and caused $65 billion in damage. New York City suffered cataclysmic breakdowns in basic infrastructure and services, including the flooding of the subway system and most major roads entering Manhattan; the destruction of hundreds of homes and a quarter million vehicles; and a power outage that plunged all of Manhattan below 14th Street into an eerie darkness for days. Hurricane Sandy accomplished what the Occupy Wall Street protests had been unable to do the previous autumn: it shut down the worlds preeminent financial hub, the New York Stock Exchange. The uncanny sight of downtown Manhattans spires plunged into darkness was an unmistakable signal that something had gone deeply awry.

The prostration of New York left me with turbulent emotions. I felt fortunate (as I had on 9/11) that my neighborhood escaped almost totally unscathed, but the city itself suddenly seemed vulnerable: the sense of certainty that underlies quotidian urban life had been dramatically interrupted. I also felt disconnected from the rest of the city: the subways did not start running again for days; I couldnt reach friends who lived in downtown Manhattan, since their power was out and their cell phones werent working; and without a car, I didnt know what was being done to help people in the most damaged areas. The citys immense size, and its disconnected and disjointed character, became painfully evident as life unfolded in my neighborhood with striking placidity, while in some other neighborhoods, those who lived above the 5th floor had no access to drinking water.

I would later discover that people I knew had been displaced by the hurricane. My colleague Fred Kaufman, a resident of downtown Manhattan, had already spent years struggling with the disruption caused by 9/11: being forced to move out, then dealing with endless construction and associated pollution once he was able to move back in. Hurricane Sandy devastated the neighborhood afresh. Many of the small businesses Fred frequented were inundated by a fifteen-foot storm surge. Billions of dollars of property had been damaged. The FDR Tunnel, not far from Freds apartment, was completely filled with water, as were most basements in the area. The noise of diesel generators pumping that water out was constant, day and night. But when I asked Fred about the psychological impact of this experience, he seemed relatively resigned. The experience of Sandy was frightening, he said, but in many ways it is constantly frightening to live in downtown New York. When disaster strikes, no amount of money or advance preparation is going to save you; at the end of the day, you have to be able to walk out of the disaster zone on foot. What matters most is knowing how to get out and having friends who can support you once you do. Yet life returned to normal for him in a matter of days.

Just across the harbor, the people of Red Hook, Brooklyn, had a different experience. Sheryl Nash-Chisholm, a Red Hook resident, watched with trepidation as the water advanced up Columbia Street toward her home on Monday night. Scenes of people on rooftops after Hurricane Katrina were not far from her mind, but she put on a brave face for her family. Still, when the lights went out, they were all terrified. How far would the floodwaters rise? They lit some candles and huddled, sleepless, until dawn. Once the storm passed and they were able to leave home, her son discovered that his car, the pride of his life, was totally submerged, a complete write-off. Sheryl did her best to console him.