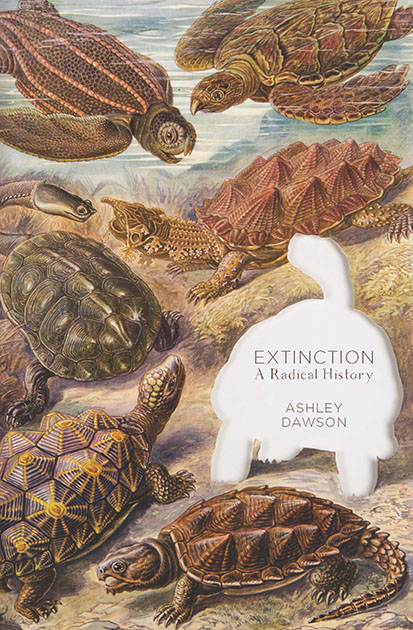

2016 Ashley Dawson

Published by OR Books, New York and London

Visit our website at www.orbooks.com

All rights information:

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher, except brief passages for review purposes.

First printing 2016

Cataloging-in-Publication data is available from the Library of Congress.

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-68219-040-1 paperback

ISBN 978-1-68219-041-8 e-book

Text design by Under|Over. Typeset by AarkMany Media, Chennai, India.

1: INTRODUCTION

His face was hacked off. Left prostrate in the red dust, to be preyed on by vultures, his body remained intact except for the obscene hole where his magnificent six foot long tusks used to be. Satao was a so-called tusker, an African elephant with a rare genetic strain that produced tusks so long that they dangled to the ground, making him a prime attraction in Kenyas Tsavo East National Park.

These beautiful tusks also made him particularly valuable to ivory poachers, who felled him with poison arrows, carved off his face to get at his tusks, and left his carcass for the flies. The grisly death of Satao, one of Africas largest elephants, is part of a violent wave of poaching that is sweeping the continent today. In 2011, twenty-five thousand African elephants were slaughtered for their ivory. An additional forty-five thousand have been killed since that time. If the present rate of slaughter continues, one of the two species of African elephants, the forest elephant, whose numbers have declined by 60 percent since 2002, is likely to be gone from Africa within a decade.

The image of Satao lying faceless in the dust is a haunting one. While the elephant as a species will probably not go extinct (since some individuals are likely to be kept alive in game reserves and zoos), the decimation of their numbers in the wild reminds us of a broader tide of extinction, the sixth mass extinction Earth has witnessed. Only tens of thousands of years ago, during the Pleistocene epoch, Earth was home to an immense variety of spectacular, large animals. From wooly mammoths to saber-toothed cats to lesser-known but equally exotic animals like giant ground sloths and car-sized glyptodonts, megafauna roamed the world freely. Today, almost all of these large animals are extinct: killed, most of the evidence suggests, by human beings.

But it is not just charismatic megafauna like elephants, rhinos, tigers, and pandas that are being pushed to the brink of extinction. Humanity lives amid, and is the cause of, a massive decimation of global biodiversity. From humble invertebrates like beetles and butterflies to various terrestrial vertebrate populations like bats and birds, species are going extinct in record numbers. For example, since 1500, 322 species of land-based vertebrates have disappeared, and the remaining populations show an average 25 percent decline in abundance around the world. This mass extinction is thus an under-acknowledged formand causeof the contemporary environmental crisis.

Although this wave of mass extinction is global, the vast majority of species destruction is concentrated in a small number of geographical hotspots. This is because biodiversity is unevenly distributed. On land, tropical rainforests are the primary nursery of biodiversity. Although they cover only 6 percent of the Earths surface, their terrestrial and aquatic habitats harbor more than half the known species on the planet. From the great Amazon basin, to the rainforests of West and Central Africa, to the jungles of Indonesia, Malaysia, and other parts of Southeast Asia, human beings are eliminating the homes of millions of species. In doing so, we are not only condemning vast numbers of species (the great majority of them still unidentified) to extinction, but we are also imperiling our own tenure on this planet.

With the publication of accessible works of science journalism such as Elizabeth Kolberts The Sixth Extinction, the word has begun to get out about the dire plight of the planets flora and fauna. Kolberts book takes readers on a terrifying tour, interviewing botanists who follow the tree line as it vaults up the side of mountains in the Andes and marine botanists who track the acidification of the oceans. The current wave of extinction, she explains, follows five previous mass extinction events that have devastated the planet over the last half billion years. This wave is predicted to be the worst catastrophe for life on Earth since the asteroid impact that destroyed the dinosaurs. Reflecting on this melancholy reality, humanities scholars have begun to write about cultures of extinction.

All too often, however, initiatives such as Obamas result in a war on poachers that ignores the underlying structural causes that are driving habitat destruction and overharvesting of animals. In the planets tropical latitudes, Parenti identifies a catastrophic convergence, a supremely destructive alignment of three factors: 1) militarization and ethnic fragmentation related to the legacy of the Cold War in postcolonial nations; 2) state failure and civil discord linked to the structural adjustment policies imposed on the global South by institutions like the World Bank in the name of debt repayment since the 1980s; and 3) climate change-fueled environmental stresses such as desertification. Parenti writes at length on the impact of this catastrophic convergence on postcolonial people and states, but the picture he provides of the stresses affecting the global South is incomplete without a consideration of the relations between humanity and the natural world in its fullest sense. We cannot understand the catastrophic convergence, that is, without discussing the decimation of biodiversity currently unfolding in the global South. Nor, conversely, can we understand extinction without an analysis of the exploitation and violence to which postcolonial nations have been subjected.

Extinction is the product of a global attack on the commons: the great trove of air, water, plants, and collectively created cultural forms such as language that have been traditionally regarded as the inheritance of humanity as a whole. Nature, the wonderfully abundant and diverse wild life of the world, is essentially a free pool of goods and labor that capital can draw on. As critics such as Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have argued, aggressive policies of trade liberalization in recent decades have been predicated on privatizing the commonstransforming ideas, information, species of plants and animals, and even DNA into private property.

Capital must expand at an ever-increasing rate or go into crisis, generating declining asset values for the owners of stocks and property, as well as factory closures, mass unemployment, and political unrest. And yet capital of course depends on continuous commodification of this environment to sustain its growth. The catastrophic rate of extinction today and the broader decline of biodiversity thus represent a direct threat to the reproduction of capital. Indeed, there is no clearer example of the tendency of capital accumulation to destroy its own conditions of reproduction than the sixth extinction. As the rate of speciationthe evolution of new speciesdrops further and further behind the rate of extinction, the specter of capitals depletion and even annihilation of the biological foundation on which it depends becomes increasingly apparent.

Next page