I found a huge blister of water forming on my bedroom wall when the wind woke me in the middle of the night. Hurricane Sandy had been buffeting the city all day, and as nightfall approached I hunkered down in my apartment in Jackson Heights, Queens, hoping that my neighborhoods elevation would bring a degree of safety. The previous day New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg had ordered the evacuation of everyone living in flood Zone A, a total of 375,000 people, and by evening the city halted all subway service, marooning people without cars in their neighborhoods. There was little to do the following day, Monday, 29 October, other than to fill the bathtub with water, stock up on batteries, and watch the sky over the city ominously darken. When the full force of the storm hit that night, the intensifying winds drove rain into the bricks and mortar of my building, which age had rendered all too permeable to such a sustained onslaught, producing a threatening bulge in the paint of my bedroom wall. I prodded the blister gingerly and mopped, slept fitfully, and then was awoken by the winds raging outside to find the blister growing larger again, in what seemed like an endless cycle. By morning, I felt exhausted but fortunate to have escaped the hurricane relatively lightly. We still had power, and taxis and delivery trucks rolled through the streets.

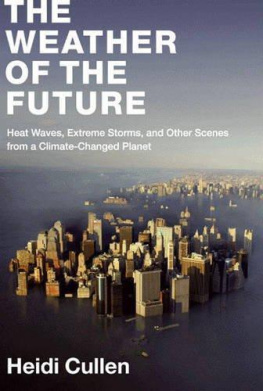

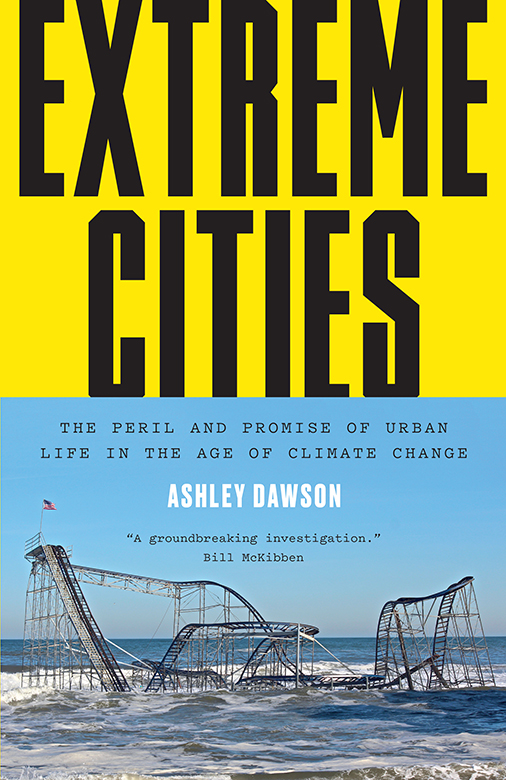

But other portions of the city had sustained major damage. The superstorm drove a wall of water into the financial district of Manhattan, capitalisms great citadel. Sandys fourteen-foot surge had flooded a power substation in Manhattans Lower East Side, causing a catastrophic short circuit that cut off electricity to all of Lower Manhattan. The surge had also inundated many low-lying areas: Red Hook, the Navy Yard, Brighton Beach, and Coney Island in Brooklyn; areas around Jamaica Bay in Queens, including the Rockaways, a barrier island where the community of Breezy Point was utterly destroyed by a fire started by short-circuiting electrical equipment. On Staten Island, a borough still mourning losses from 9/11, beachside communities like Ocean Breeze and Oakwood Beach had flooded catastrophically.

In the days following Sandys landfall, it became clear that it had been one of the most destructive storms ever to hit the United States. The storm killed 160 people in the New York metropolitan region and caused $65 billion in damage. New York City suffered cataclysmic breakdowns in basic infrastructure and services, including the flooding of the subway system and most major roads entering Manhattan; the destruction of hundreds of homes and a quarter million vehicles; and a power outage that plunged all of Manhattan below 14th Street into an eerie darkness for days. Hurricane Sandy accomplished what the Occupy Wall Street protests had been unable to do the previous autumn: it shut down the worlds preeminent financial hub, the New York Stock Exchange. The uncanny sight of downtown Manhattans spires plunged into darkness was an unmistakable signal that something had gone deeply awry.

The prostration of New York left me with turbulent emotions. I felt fortunate (as I had on 9/11) that my neighborhood escaped almost totally unscathed, but the city itself suddenly seemed vulnerable: the sense of certainty that underlies quotidian urban life had been dramatically interrupted.werent working; and without a car, I didnt know what was being done to help people in the most damaged areas. The citys immense size, and its disconnected and disjointed character, became painfully evident as life unfolded in my neighborhood with striking placidity, while in some other neighborhoods, those who lived above the 5th floor had no access to drinking water.

I would later discover that people I knew had been displaced by the hurricane. My colleague Fred Kaufman, a resident of downtown Manhattan, had already spent years struggling with the disruption caused by 9/11: being forced to move out, then dealing with endless construction and associated pollution once he was able to move back in. Hurricane Sandy devastated the neighborhood afresh. Many of the small businesses Fred frequented were inundated by a fifteen-foot storm surge. Billions of dollars of property had been damaged. The FDR Tunnel, not far from Freds apartment, was completely filled with water, as were most basements in the area. The noise of diesel generators pumping that water out was constant, day and night. But when I asked Fred about the psychological impact of this experience, he seemed relatively resigned. The experience of Sandy was frightening, he said, but in many ways it is constantly frightening to live in downtown New York. When disaster strikes, no amount of money or advance preparation is going to save you; at the end of the day, you have to be able to walk out of the disaster zone on foot. What matters most is knowing how to get out and having friends who can support you once you do. Yet life returned to normal for him in a matter of days.

Just across the harbor, the people of Red Hook, Brooklyn, had a different experience. Sheryl Nash-Chisholm, a Red Hook resident, watched with trepidation as the water advanced up Columbia Street toward her home on Monday night.home, her son discovered that his car, the pride of his life, was totally submerged, a complete write-off. Sheryl did her best to console him.

The devastation in Red Hook was vast. When Hurricane Sandy struck, the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) had shut down elevators, boilers, and electrical systems in public housing complexes across the city, including those in Zone A neighborhoods like Red Hook. With roughly 8,000 residents, NYCHAs Red Hook Houses complex is the largest public housing development in Brooklyn. When the power went down, the heat turned off and the water stopped running, leaving the residents of Red Hook Houses in life-threatening conditions.

The morning after the storm, Sheryl headed over to the Red Hook Initiative (RHI), a community organization dedicated to empowering the youth of the neighborhood. She is one of their key organizers. The building, unlike many others in Red Hook, was largely spared flooding during the storm and had also kept its power supply, so after failing to reach the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) on the phone, Sheryl began coordinating with residents of Red Hook Houses to turn RHI into a hub for the community. Within hours, RHI was providing power for charging cell phones, so that community members could let family members elsewhere know that they were okay. The building also provided a warm space, where residents of the chilly public housing complex could escape hypothermia. By the end of the day, hundreds of volunteers with what would become known as Occupy Sandy had arrived at RHI on bicycles, bringing much needed donations of batteries, candles, blankets, and canned food. A colleague of Sheryls organized medical delegations to Red Hook Houses to check on elderly residents who needed medical attention, fresh medical supplies, and even basic needs like drinking water and food. For the next three days, RHI was the principal center for organizing the community, gathering donations from around the city and delivering food and other supplies to needy people living in public housing and other parts of Red Hook. For Sheryl, it was an exhausting but exhilarating sequence of days, a time in which her personal energies were strained but her faith in the solidarity of her community was reaffirmed. The federal government and relief agencies like the Red Cross would not arrive in the neighborhood with supplies for many days.