My first and deepest thanks must go to Vic Gatrell, whose special paper at Cambridge, The Politics of Laughter, inspired my love of visual culture and introduced me to William Hones trials and satires. Vics knowledge of satire is second to none, and his enthusiasm contagious: his classes were the only things that got me out of bed before 9 during four years at university. Thanks also to the Master and Fellows of Pembroke College, in particular Michael Kuczynski, Dr Jon Parry and the late Dr Mark Kaplanoff, whose long, long lunches kept my spirits up.

And to Rowan Pelling, who introduced me to Clare Conville, the very best of agents. Clares sharp mind, inexhaustible patience and great company kept me going during the writing of this book; thanks, Clare, for the bottles of champagne and lunches of lobster which, along with your friendship, encouraged me to write when I would otherwise have given up.

I would also like to thank, for many and different reasons, Hattie and Chris Pask, David Maxwell, James Rivett, Elisa Lodato, Patrick Walsh, Matthew Hook, Matthew Wilson and all friends and family who tolerated my absences. I am a Luddite when it comes to computers, so special thanks go to Andrew Singleton and Ross Monro for technical advice. The staff of the Rare Books Room of the British Library have been consistently helpful and cheery. I am indebted to Finbar McDonnel for help with the cartoons. Fred Hodder read an early draft and his suggestions were incorporated; for such original comments and peerless companionship all his friends miss him dearly.

I am grateful for the unfailing help from everyone at Faber, especially the people I worked with most closely, Lesley Felce and Lucy Owen. Walter Donohue has been the best of editors; his commitment to the book, generosity and insights contributed so much to the writing. He has made the process of writing what it should be: tremendous fun. I have enjoyed every moment working with him, especially when it coincided with lunch.

Public opinion can never exist as a power in the State, unless there exist also persons who expose to hatred and contempt those Ministers and those laws which they conceive to be detrimental to the interests of the community.

Yellow Dwarf, 1818

If I cannot do a thing in my own way, I never can do it at all.

William Hone, in a letter to Francis Place, 1824

In October 1842, Charles Dickens accompanied George Cruikshank to a funeral at Abney Park Cemetery, Stoke Newington, on a day he described as muddy, foggy, wet, dark, cold, and unutterably wretched in every possible respect. They were going to pay their respects to William Hone. Dickens had met Hone for the only time a few weeks before when he had travelled to the old mans home in Tottenham. The meeting had been arranged by their mutual friend George Cruikshank, the illustrator of books written by both Hone and Dickens.

God knows it was miserable enough, wrote Dickens, for the widow and children were crying bitterly in one corner, and the other mourners mere people of ceremony, who cared no more for the dead man than the hearse did were talking quite coolly and carelessly in another; and the contrast was as painful and distressing as anything I ever saw.

The novelist was moved and affected by the gloomy scene. But what made it worse was the dark comedy that often accompanies an awkward English funeral. Dickens found eccentric George Cruikshanks behaviour and appearance irrepressibly funny, especially in stark contrast to the sombre rituals of a nonconformist funeral. It was for Dickens, a scene of mingled comicality and seriousness which has choked me at dinner ever since.

Now, [Cruikshank] has enormous whiskers, which straggle all down his throat in such weather, and stick out in front of him, like a partially unravelled birds-nest; so that he looks queer enough at the best, but when he is very wet, and in a state between jollity (he is always very jolly with me) and the deepest gravity (going to a funeral, you know), it is utterly impossible to resist him, especially as he makes the strangest remarks the mind of man can conceive, without any intention of being funny, but rather meaning to be philosophical. I really cried with an irresistible sense of his comicality all the way

When Cruikshank was dressed in the black cloak and hat of chief mourner, Dickens almost had to leave the room because the sight was too much. It soon became obvious that, as early as his last rites, William Hone had slipped from the memories even of his closest friends; his obsequies quickly degenerated into farce and petty quarrels.

The mourners went into the parlour, where, as Dickens recalled, there was

an independent clergyman present, with his bands on, and a Bible under his arm, who, as soon as we were seated, addressed us thus in a loud voice:

Mr C, have you seen a paragraph respecting our departed friend, which has gone the round of the morning papers?

Yes, sir, says C, I have, looking very hard at me the while, for he had told me with some pride coming down that it was his composition.

Oh! said the clergyman, then you will agree with me, Mr C, that it is not only an insult to me, who am the servant of the Almighty, but an insult to the Almighty, whose servant I am.

How is that sir? said C.

It is stated, Mr C, in that paragraph, that when Mr H[one] failed in business as a bookseller, he was persuaded by me to try the pulpit, which is false, incorrect, unchristian, in a manner blasphemous, and in all respects contemptible. Let us pray. With which and in the same breath, he knelt down, as we all did, and began a very miserable jumble of an extemporary prayer.

At that instant Dickens was really penetrated with sorrow for the family and Cruikshank was upon his knees and sobbing for the loss of an old friend. But the moment of poignancy was ruined when George muttered through his tears that if it wasnt a clergyman, and it wasnt a funeral, hed have punched his head. I felt, poor Dickens had to admit, as if nothing but convulsions could possibly relieve me

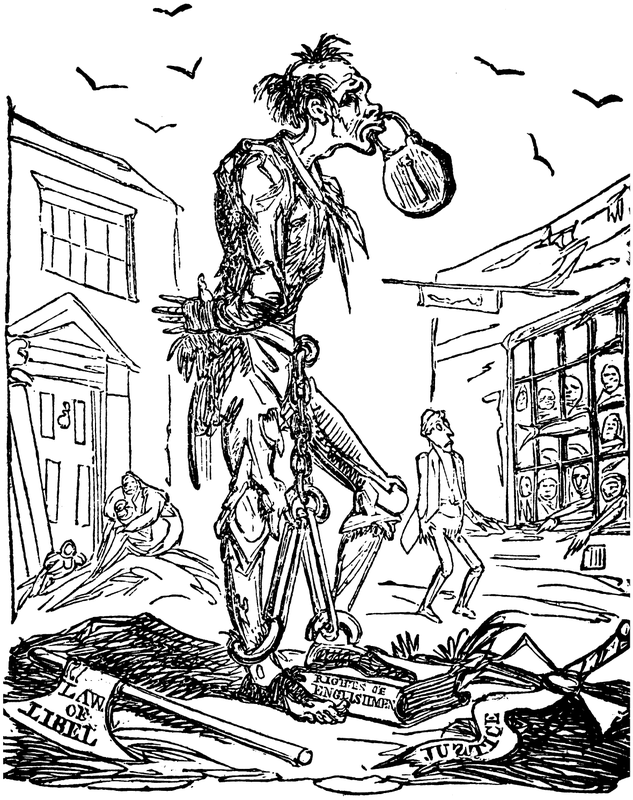

In 1842, Dickens was thirty years old, a former parliamentary reporter and author of five novels. By this time, the British press was one of the freest and most intrusive in the world, boasting a power over every act of government; in turn, it was flattered by politicians as the Fourth Estate. Many bemoaned its licentiousness, but few could deny its influence and constitutional liberties. Meeting the old man in Tottenham must have been a reminder to Dickens of how recent these things were. In 1809, when Hone began his career in journalism, Jeremy Bentham wrote that the freedom of the press existed in a sort of abortive embryo state.