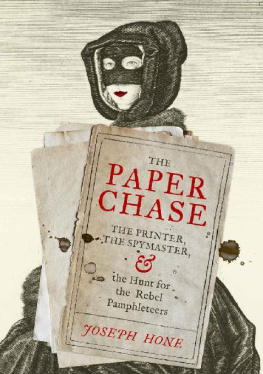

Joseph Hone

THE PAPER CHASE

The Printer, the Spymaster, and the Hunt for the Rebel Pamphleteers

Contents

About the Author

Dr Joseph Hone is a writer and academic based at Newcastle University, where he researches and teaches the literature of the long eighteenth century. He was educated at Oxford and has held fellowships at Cambridge, Harvard, Yale, and the Institute of English Studies in London. His first book, Literature and Party Politics at the Accession of Queen Anne (2017) was shortlisted for the University English Book Prize. He is currently preparing the early verse of Alexander Pope for a major new edition.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Literature and Party Politics at the Accession of Queen Anne

To my parents

Authors Note

The story told in this book occurred in an age before uniform standards of spelling, grammar, and typography had been established. While original orthography does help preserve some of the texture of the age, archaic spelling can also be disorienting for readers unaccustomed to the distinctive patterns of early modern writing. I have adopted a compromise. In the service of clarity, I have standardised quotations from primary sources. Most idiosyncrasies of spelling and some unusual formatting features are preserved, but I regularise the alphabet, some confusing punctuation, and most quirks of typography, such as the capitalisation of nouns and italicisation of names, which was routine in this period but can be distracting to the modern eye. Italics for emphasis or which have some effect on meaning have been preserved. Contracted and dashed words and names have silently been expanded, superscripted letters silently lowered, and ampersands routinely standardised to and. The old method of denoting pounds by an l has been replaced by the modern symbol . Underlined text in handwritten letters has been italicised, as have the titles of books. In the spirit of authenticity, all reported speech is quoted verbatim from contemporary documents. Unless otherwise stated, all dates are given in the old-style Julian calendar used in England until 1752, but with the new year beginning on 1 January and not 25 March.

Prologue

The Woman in the Vizard Mask

The summer of 1705 had been blisteringly hot. Farmland all across Englands southern pastures was slowly succumbing to drought. At Greenwich, on the southern banks of the Thames, the ageing polymath John Evelyn noted in his diary that all the country was burnt up. By the middle of June it had not rained in London for over a month. There was no wind. He could not remember having experienced such exceedingly dry and hot weather for many years. The city streets reeked from the drying ooze of human waste and sweat.

A woman walked down Fetter Lane, in the busy legal district of Holborn. Through the dust and crowds she cut a striking figure. Observers described her as a shapely woman, something taller than average and pretty burley,

It was like entering a different city. The dome of Christopher Wrens new cathedral at St Pauls loomed only half a mile to the east, still clad in scaffolding and ladders; but the woman could not have seen it. This warren of small alleys and courtyards had narrowly escaped the fire which had consumed much of the city some forty years earlier. The buildings here were hundreds of years old, jutting out into the street in a ramshackle mishmash of gnarled wood and plaster. The shade was welcome. Before long, though, her eyes adjusted and the grime of the place became visible. The woman had learned from her previous visits not to let this bother her. She marched over to an innocuous-looking building, pulled a vizard mask of black velvet out of her bag, covered her face, and knocked on the door.

A robust Welshman answered, his hands blackened with ink. His name was David Edwards, a skilled printer with more than twenty years experience in the trade. On her previous two visits the woman had found only his wife, Mary, and promised to return another day. In turn, Mary had warned her husband to expect a suspicious-looking customer. Edwards dealt with plenty of shady types in his business and was a keen reader of people. Although the womans face was covered, he was struck by her voice, the melody of which he claimed to recall a full year later. The womans request was quite simple. She came with copy to be printed,

While Edwards sat reading the first five or six pages of the manuscript, his visitor explained that this essay had been approved by some powerful men and was for the advantage of the church. Later, under very different circumstances, he claimed to have been shocked by what he read. Certainly the book would sell; but in the present climate it was simply too dangerous for him to print such a vicious polemic. Eyes were everywhere. Turning back to the woman, and noticing that she had not removed her mask, he scrupled the doing of it and told her he had had a great deal of trouble already. He mentioned George Sawbridge, over at the sign of the three fleur-de-lis in Little Britain. Why didnt she take it to him? he asked, shuffling the woman towards the door. Sawbridge was Edwardss go-to business partner when dealing with controversial texts. He would put his name on the covers of books that Edwards manufactured, keeping the printer out of the limelight.

By no means, she replied, sidestepping the printer and taking a seat: he had been spoke of for it, but not approved. If Edwards wanted to sell the book, he would have to do all the work himself. Eventually, after some persuasion and many arguments, he agreed to take on the job. The woman assured him that there was no harm in it and that this could even be the making of him. She would not reveal the identity of the author or authors of the manuscript when he asked, but alluded cryptically to men in high places who would stand by him if necessary. Edwards would never meet them or know their names, she explained, but nor would he be entirely without allies. The printer would not forget this promise.

Having agreed in principle to print the book, Edwards now moved on to the terms of the deal. To have maximum impact the pamphlet would need to be printed and ready for sale within the fortnight. This would be pushing Edwards and his young press team to the limit; but with some extra labour they could manage it. In exchange for the rights to print the book, the masked woman demanded two hundred and fifty copies of the finished product. Edwards was free to keep any and all profits from the remainder of the print run and from any further editions of the text. The terms being settled, the woman passed over one half of an indented paper as a token for the delivery. This sheet had been cut in two along a jagged line. Edwards was only to hand over the books when a courier arrived bearing the corresponding half of the paper. Until then, the masked woman urged, Edwards was to keep this job secret. Nobody beyond his inner circle could know. With those words still ringing in Edwardss ears, she stood, turned, and disappeared into the street.

Within days of printing The Memorial of the Church of England, Edwards was on the run, chased by government agents acting on the orders of the most important spymaster in the land. His wife, Mary, had already been taken into custody. I woud have burnt the book before I had concernd my self with it, the printer later explained in a letter to his pursuers, had I understood their drift. And yet why should Edwards regret not condemning a manuscript to the flames? Why should he need to flee his home and leave his business in tatters? After all, was this not the burgeoning age of enlightenment and liberty? Of ruthless satirists such as Jonathan Swift and of great thinkers such as John Locke and Isaac Newton?

Next page