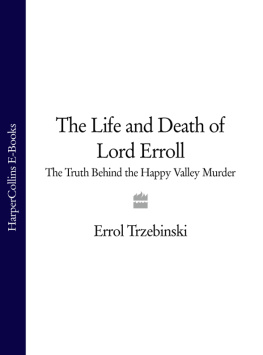

White Mischief

The Murder of Lord Erroll

James Fox

For Thomas

CONTENTS

NOTE

In earlier editions of this book I mistakenly wrote that Sir Iain Moncreiffe of that Ilk had inserted in Debretts the information that Lord Erroll had been mentioned in despatches for his part in the Eritrean operations when Italy entered the war. In fact, there is no such insertion in Debretts. Burkes, however, does link Errolls despatches with the Eritrean campaign, which took place in June and July 1940, at which time Erroll was a staff captain. But I believe that the mention in despatches (posthumously gazetted) was for Errolls work at East Africa Command in Nairobi and for his organising the troops for the subsequent Abyssinian campaign, which was launched on the day he was murdered.

February 1983 J.F.

INTRODUCTION

In the early hours of January 24th, 1941 when Britain was preoccupied with surviving the Blitz, the body of Josslyn Hay, Earl of Erroll, was discovered on the floor of his Buick at a road junction some miles outside Nairobi, with a bullet through the head. The two Africans who came upon the car, lying almost on its side in the grass beside the road, found its headlights blazing but no trace of an assailant.

Lord Erroll was the hereditary High Constable of Scotland and, by precedence, the first subject in Scotland after the Royal Family. At thirty-nine, he was a leading figure in Kenyas colonial community and had recently been appointed Military Secretary. He was notorious, locally, for his exploits with married women, and had been much praised, ever since he was at Eton, for his charm and his great good looks. It was only in the last five years that Erroll had devoted himself to anything more serious than the pursuit of pleasure. But already he was projected as the future leader of the white settlers.

There were many people in Kenya who had a motive for killing Erroll, and many who had the opportunity that night. Yet nobody was convicted of his murder, and the question of who killed him, who fired the gun at the junction, became a classic mystery. It was at the same time a scandal and a cause clbre which seemed to epitomise the extravagant way of life of an aristocratic section of the white community in Kenya at the moment of greatest danger for Britain and the West.

Erroll was killed on the very day that the campaign was launched in Nairobi to remove Mussolinis army from Abyssinia. It was Erroll, ironically, as Military Secretary, who had been responsible for gathering the European and African troops for that campaign. The Dunkirk evacuation in May and June 1940, and the bombing of Britains cities, weighed heavily on the conscience of the white community in Kenya, who were keenly aware of their isolation from the main war effort. The last thing they wanted was for Nairobis social elite to be paraded in court, making world headlines which competed on page one with news of the war itself. It was a source of acute embarrassment. One headline read: Passionate Peer Gets His.

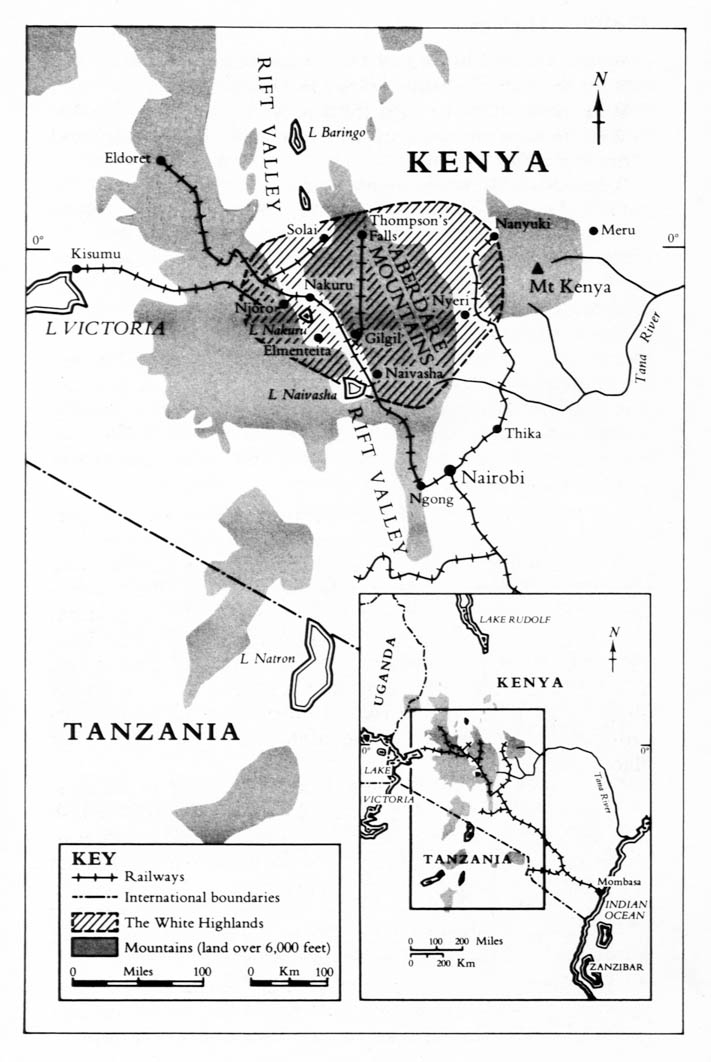

The story confirmed the licentious image of the Colony in the popular imagination in Britain and America, and revived the legend of Happy Valley, an area in the White Highlands which had been notorious since the 1920s as a playground for aristocratic fugitives of all kinds.

Happy Valley originated with Erroll himself and with Lady Idina Gordon, who later became his wife, and who set up house there in 1924. Friends from England brought home tales of glorious entertainment in an exhilarating landscape, surrounded by titled guests and many, many servants.

In New York and London the legend grew up of a set of socialites in the Aberdares whose existence was a permanent feast of dissipation and sensuous pleasure. Happy Valley was the byword for this way of life. Rumours circulated about endless orgies, of wife swapping, drinking and stripping, often embellished in the heat of gossip. The Wanjohi River was said to run with cocktails and there was that joke, quickly worn to death by its own success: are you married or do you live in Kenya? To have gone anywhere near Happy Valley was to have lost all innocence, to have submitted to the most vicious passions.

With Errolls murder and the scandal that followed, the spirit of Happy Valley was broken for ever. For the whites in Kenya it signalled the end of a way of life which stretched back three decades. The spell was broken, the ruling confidence that underpinned their unique occupation was gone, and it was never to be the same again.

Yet the mystery of who killed Lord Erroll survived and flourished, and continues to exert a strange power over all who come into contact with it. In Kenyas remaining white community, it is still talked about as if it had happened yesterday. The virus of speculation has become endemic, and even today the place is alive with experts. One is told of many different people who alone hold the key to it all, but who will never be persuaded to tell. Others, including a former Governor of Kenya, achieved local fame by promising to leave the solution in written testimony in their willsbut the executors have always been left empty-handed. Much of this oral history is encrusted with distortion and incestuous folklore, each version fiercely held to be the trutha warning to anyone broaching the subject in the Muthaiga Country Club.

So compelling was the mystery that throughout the 1960s it dominated the thoughts of a man of letters as distinguished as Cyril Connolly. In the spring of 1969, twenty-eight years after the event, Connolly and I decided to investigate the story for the Sunday Times Magazine, where I worked as a staff writer.

We discovered that everything written on the subjectincluding the only bookdepended on the public record of the trial, adding nothing new, and came no closer to a solution than the Nairobi High Court in 1941. To our surprise, no one had returned to the original sources, or had gathered and sifted the popular wisdom, or had filled in the glaring empty spaces in the evidence collected by the Nairobi C.I.D. in the weeks after the murder.

Our article, which we called Christmas at Karen, turned out to be the prelude to a much longer quest. It generated an unexpected response, awakening memories and producing a mass of new evidence in its wake. The trail led us on. And Connolly, the literary critic par excellence, did not take his obsessions lightly. The volumes of notes that he left me in his will testify to that. My own fascination with the story, shared with Connolly as I played Watson to his Holmes in that year when we worked closely together, was revived when I opened the notebooks again, soon after his death in 1974. I decided to pursue the trail that we had embarked upon together.

Our joint obsession was primarily with the enigma, which Connolly approached like a novelist, believing in a solution through the study of character. But the story also touched off his social phobias and his curiosity about the beau monde of the 1930s, about the titled aristocracy and their dense network of kinship. He swotted up Debretts with scholarly reverence, as if it were the Old Testament itself.

One aspect that particularly appealed to Connolly was that several of the male characters in the story, including Lord Erroll, had been contemporaries of his at Etonthe Eton he described in