Table of Contents

FROM THE PAGES OF

THE GREAT ESCAPES

It is not for a single generation alone, numbering three millionssublime as would be that effortthat we are working. It is for Humanity, the wide world over, not only now, but for all coming time, and all future generations.

(from Narrative of William W. Brown, page 9)

During the last night that I served in slavery I did not close my eyes a single moment. When not thinking of the future, my mind dwelt on the past. The love of a dear mother, a dear sister, and three dear brothers, yet living, caused me to shed many tears.

(from Narrative of William W. Brown, page 52)

Let us declare through the public journals of our country, that the question of slavery is not and shall not be open for discussion: that the system is too deep-rooted among us, and must remain forever; that the very moment any private individual attempts to lecture us upon its evils and immorality, and the necessity of putting means in operation to secure us from them, in the same moment his tongue shall be cut out and cast upon the dunghill.Columbia (S. C.) Telescope.

(from Narrative of William W. Brown, page 74)

My book will represent, if possible, the beautiful side of the picture of slavery. (from Narrative of Henry Box Brown, page 100)

A cold sweat now covered me from head to foot. Death seemed my inevitable fate, and every moment I expected to feel the blood flowing over me, which had burst from my veins.

(from Narrative of Henry Box Brown, page 136)

I happened to be in the City of PhiladelphiaI have told the story to the convention already, but I will tell it againin the midst of an excitement that was caused by the arrival of a man in a box. I measured it myself; three feet one inch long, two feet wide, and two feet six inches deep. In that box a man was entombed for twenty seven hours.

(from Narrative of Henry Box Brown, page 158)

I have since learned that it was the famous Nat Turners insurrection. Many slaves were whipped, hung, and cut down with the swords in the streets; and some that were found away from their quarters after dark, were shot; the whole city was in the utmost excitement, and the whites seemed terrified beyond measure, so true it is that the wicked flee when no man pursueth.

(from Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, page 185)

Thus passed my child from my presenceit was my own childI loved it with all the fondness of a father; but things were so ordered that I could only say, farewell, and leave it to pass in its chains while I looked for the approach of another gang in which my wife was also loaded with chains.

(from Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown, pages 203204)

It may be remembered that slavery in America is not at all confined to persons of any particular complexion; there are a very large number of slaves as white as any one.

(from Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, page 225)

Under these circumstances, it is the almost unanimous opinion of their best friends, that they should quit America as speedily as possible, and seek an asylum in England! Oh! shame, shame upon us, that Americans, whose fathers fought against Great Britain, in order to be free, should have to acknowledge this disgraceful fact!

(from Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, page 274)

In short, it is well known in England, if not all over the world, that the Americans, as a people, are notoriously mean and cruel towards all coloured persons, whether they are bond or free.

(from Running a Thousand Miles for Freedom, page 286)

THE GREAT ESCAPES

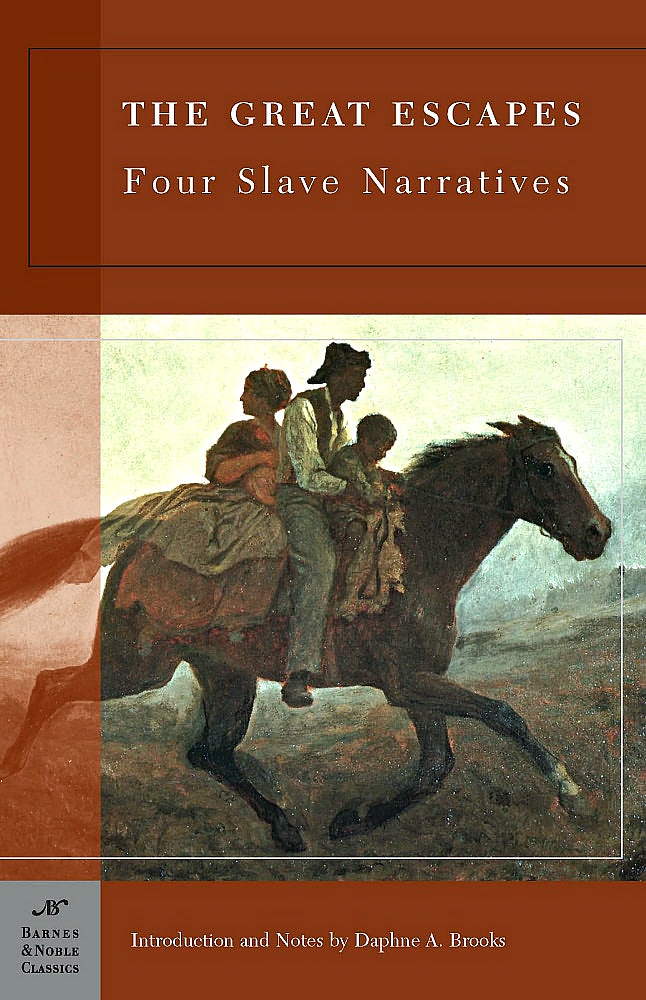

The personal histories of slaves in the preCivil War American South offer the modern reader a unique portrait of the African-American slave and of a nation divided over slavery, the central moral issue of the time. Slave narratives played an important role in the antislavery movement, individualizing the slaves and providing a window onto their lives for skeptics and galvanizing white sympathizers to action. Four remarkable examples are narratives by William Wells Brown, Henry Box Brown, and William and Ellen Craft.

William Wells Brown was born in 1814 in Lexington, Kentucky. His mother, Elizabeth, was a slave, and his father, George Higgins, was a white relative of Browns owner. Browns owners hired him out in different capacities; he was employed on a riverboat and as a field slave, a house slave, a typesetter for a printer, and even an assistant to a slave-trader. In 1834 Brown escaped his owner and made his way North, where he worked on a Lake Erie steamboat and conducted runaway slaves to Canada as part of the Underground Railroad; his intelligence and gift for oratory made him a sought-after lecturer for the anti-slavery movement. In 1847 he moved to Boston, where he published Narrative of William W. Brown, A Fugitive Slave, Written by Himself. The popular autobiography described the institution of slavery in vivid yet dispassionate detail.

Brown embarked on a lecture tour of Europe in 1849 and did not return to the United States for five years, partly to avoid the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. His time abroad inspired Three Years in Europe; or, Places I Have Seen and People I Have Met (1852); he also published Clotel (1853), the first novel by an African American. Like Frederick Douglass, Brown served the abolition movement through his speeches and published writings; he wrote major works on black history, including The Black Man (1863) and The Negro in the American Revolution (1867). William Wells Brown spent the last decades of his life in Boston, he died in Chelsea, Massachusetts, on November 6, 1884.

Henry Box Brown was born around 1815 in Louisa County, Virginia. At age fifteen, he was separated from his family and sent to work in a Richmond tobacco factory. In Richmond, Brown married Nancy, a slave washerwoman, and the two had three children. When his wife and children were sold to a distant slaveholder, Brown, devastated, resolved to escape his bondage and in 1848 had himself mailed in a tiny wooden crate to the Anti-Slavery Society of Philadelphia. With only a jug of water, Brown survived the 300-mile, twenty-seven-hour journey. He set down his story in two booksNarrative of Henry Box Brown, Who Escaped from Slavery Enclosed in a Box 3 Feet Long and 2 Wide (1849) and Narrative of the Life of Henry Box Brown (1851)and, in illustrated form, as a scrolling panorama called Mirror of Slavery (1850). For a time, Brown told his story in the service of the anti-slavery movement and proved a popular speaker. When the Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850, he fled to England; by 1878 he had dropped out of public view.

William and Ellen Craft were slaves in Macon County, Georgia. William was a skilled cabinetmaker, while Ellen worked as a house slave. Neither endured the brutal physical circumstances of many slaves in the American South, yet as the property of separate slaveholders, they lived in fear of separation and longed for their freedom. In 1848 they determined to escape. Ellen, whose skin was so fair she was often mistaken for a white woman, disguised herself as an invalid, wrapping herself in bandages, while William pretended to be his masters faithful slave. The ruse worked, and the two escaped to Philadelphia and then to Boston. There they joined the anti-slavery movement, recounting their escape before rapt audiences.

Next page