This edition is published by Muriwai Books www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books muriwaibooks@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1961 under the same title.

Muriwai Books 2018, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

JASON

BY

HENRY TREECE

PROLOGUEThe Cretan

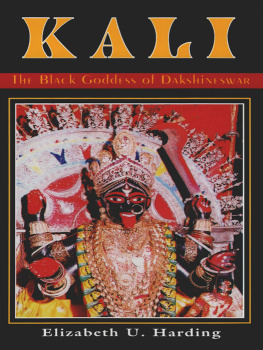

FOR three days the Minoan had crouched, small and dark and afraid, hidden in the fern-hung mouth of the cave. Sometimes he scraped lichen from the limestone rocks about him, stuffing his mouth with the pulpy mash to allay his maddening hunger, sometimes sucking at the little pebbles that lay on the floor of the cave and pretending they were the fine fat olives of his native Crete; the Crete he had known before the brown-haired Achaeans had stormed into the crumbling harbour and made him a slave. The great Crete of Minos, whose ships once fetched tribute from every port in the world, whose bulls snuffed proudly in the Labyrinth arena at each festival, whose round-breasted priestesses were tireless in sounding the praises of the Mother, the Womb of All Men in her many guisesDia, Aphrodite, Hera, Hecate. All one, all the Mother who would nourish her people; who asked in return only the blood of the sacred king.

But when the bearded Hellene barbarians had rushed up the shore that afternoon after the last earthquake, sacking the great palace at Cnossus, wantonly slaughtering the sacred bulls and raping the gold-decked priestesses, even making water on the shrines, the Mother who had promised so much raised no hand to stop the invaders, no finger to strike them blind or mad.

Why had she not saved her children, the Minoan wondered? Was it because old Minos had slackened in his devotions? Or because Ariadne, the princess-priestess, had sailed away from the sacred shrines with the unbeliever, Theseus?

The Minoan leaned against the rock-wall, almost witless with hunger. He had last eaten four days beforea crust of dry barley bread and a crumb of goat-cheese snatched from the hand of a little girl who sat singing fables among the wild thyme, watching the black-faced sheep.

Do not be afraid, little one, I shall not hurt you, he said to her. I am hungry, that is all. But perhaps it was his strange Cretan speech, or the old livid scars of the slave-masters whiplash across his thin brown body that frightened her; perhaps his long matted black hair, that hung halfway down his furrowed back...She ran away squealing, her flaxen hair flying in the wind. Then he had had to run too, eating as he went, in case her father or her brothers should come after him with their long bronze swords or throwing-spears.

Now, after his grim journey over the mountain, he was in the cave mouth, the culvert, hidden by newly-sprouting fern. At least he did not suffer from thirst here. Clear spring water, flowing down from Mount Pelion, gushed out of the mouth of the culvert, icy cold, almost knee-deep. Sometimes he was so weak that he could not balance astride the stream to keep dry and was forced to stand in it until he could regain his strength. His feet and legs were chilled to the bone then. Like his mind, his life itself, they hardly seemed to belong to him.

Once he had been a merchant-prince himself, master of many olive groves and of great cattle-herds. Now he was nothinga man old before his time by years of slavery in the low shafts of the goldmines in far northern Paeonia, or crouched coughing in the damp in the lead-shafts under Mount Ossa.

He drew the strip of goatskin about his waist, his only dress, tightening it with a hide thong. Once he had worn fine silks from Egypt, and had slaves of his own to smooth aromatic balms into his skin. Now his hands were rough and misshapen, his skin cracked and covered with sores. If he walked into Cnossus, they would not know him, his teeth broken, his hair matted and shaggy, the hide about his loins stinking. Yet he had once worn gold and amethyst beads, and had his own box at the bull-ring at Cnossus, where he watched the boys and girls from Athens, the frightened young bull-leapers who were to exercise themselves for the glory of the All-Mother and her son, Minos.

The Cretan stumbled to the mouth of the culvert and looked out. On the horizon, grey-blue in the late afternoon, stood the high snow-covered shoulder of Mount Pelion, noble and strong, but foreign, with its clusters of pine woods. Then came the rolling downs, where sheep were grazed and the sound of the shepherds pipes made mad the heat of the afternoon. Then, so close at hand that he could have struck them with a pebble, had he the strength to throw one, a small grove or garden, hedged round with clumps of oleander and laurel, and towering over them, three dark cypresses that bowed with every breath of wind from the sea. Aconites still grew in the shade.

The clear water from the culvert in which he stood flowed down to that little grove, into a square bath with marble sides, its floor paved with a rude mosaic of coloured stones, not like the fine patterns of Crete, but at least something to remind him that, here in Thessaly, there had once lived men who claimed kinship with Minos and made their regular yearly voyages to Cnossus for the great markets and feasts. Above the bath, in the rock, were carved a moon-sign and an axe: tokens of the Mother Goddess.

Suddenly the Minoan froze, his heart thumping with terror once more. He heard footsteps beyond that rock above the little grove. It could be a guard, leather-clad and bearded, coming to look for him, carrying the long bronze sword and the two spears that he feared. He had seen a runaway slave taken in Larissa less than a week before. The tall fair-haired Hellenes had used him for spear-practice, against the door of a barn. As the wretch shuddered, skewered like a frog with the bronze spears in him, the Hellenes had watched him for a while, sitting on their shaggy ponies, laughing. Then their captain had kicked his mount forward and leaning down, had ripped the mans stomach open with his long sword. The creature was still alive and screaming while his blood dripped to the dusty ground at his feet, steaming.

Men did not do this in Crete in the great days. A bull-leaper stupid enough to get gored was quickly finished by the Labyrinth servants. Two blows at the nape of the neck with the little moon-shaped stone axes, the goddesses weapon, and it was all over. No nastiness like this Hellene thing. No standing round and watching while a man lost his courage and his dignity. That was the right way, the way the Mother had ordained it, the way that men were forgetting, now that the Hellenes were coming southwards in their hordes to destroy the old world, the world that had lasted thousands of years.