Contents

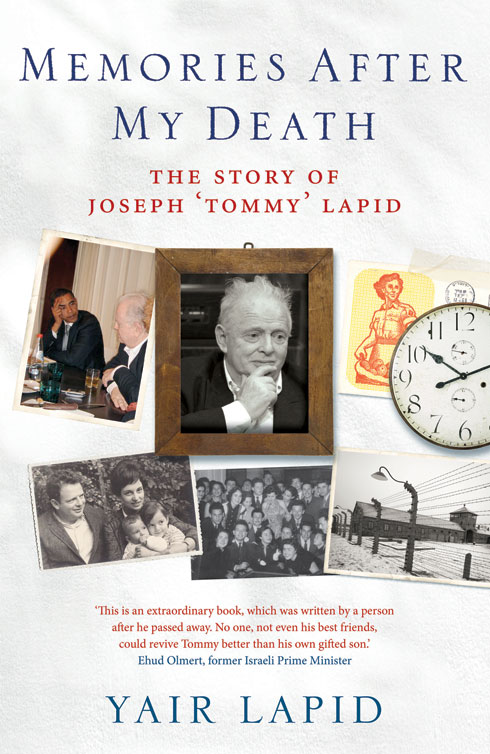

T ommy Lapid was my best friend.

It was a miracle that two people who had such a different personal background could find a common emotional language that created a bond of love and deep commitment.

As you'll find out reading Tommy's life story, he was a man with unparalleled devotion to the memories of himself, his family and his people, and an enormous power to emerge with great strength to be a dominant part of building a new and different future.

This is first of all a personal story of one's life of one person, of one family. But it is also a story of a generation that is disappearing.

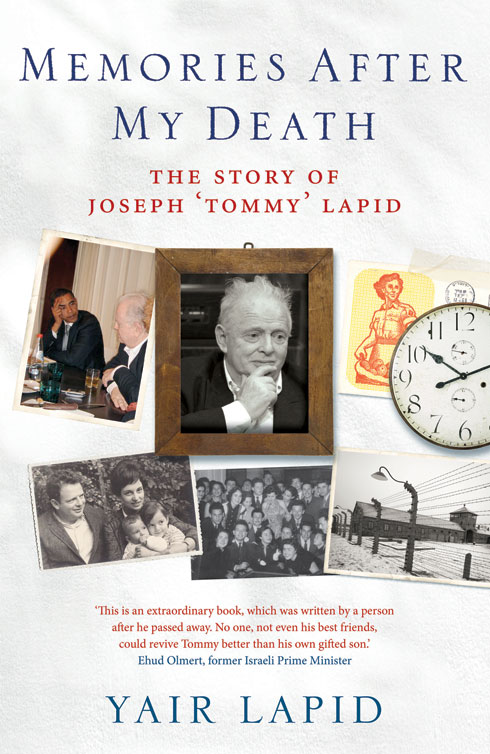

This is an extraordinary book, which was written by a person after he passed away, and will continue to be a source of endless pain and hope.

When one reads the story of Tommy Lapid he can't escape the inevitable feeling that the man who is not with us anymore is very much alive and keeps sharing with us all those observations about his life, the world and family that he lost, the family and new life he created and the love for his country which was a source of endless pride and hope that inspired him.

The voice is Tommy's, the spirit is his, but the writing is of Yair. No one, not even his best friends, could revive Tommy better than his own gifted son.

Ehud Olmert

(Ex-Prime Minister of Israel)

I am writing this book after my death. Most people write nothing after they die, but I am not most people.

Or maybe I am. My biography is so full of contradictions that sometimes I used to think and not only I that I contain everyone I ever knew. At birth I was named Joseph after a grandfather I never met and Tommy after a Hungarian prince from a long-forgotten dynasty, and I held on to both names throughout my life. I was the most famous atheist in Israel, the public and bitter enemy of Orthodoxy, but I represented (faithfully, I hope) the entirety of Jewish fate. I was despised, but remarkably popular, a polite and educated European intellectual and a red-cheeked defender of the rights of the people whose outbursts were legendary. A conservative chauvinist who knew how to appreciate the figure of a beautiful woman and loved Rembrandt, Mozart and Brecht, and a folksy speaker who could fire up a crowd with pithy one-liners. A leftist who supported partitioning Israel and a rightist whom Prime Minister Menahem Begin chose to run the countrys lone television station. I was an orphan who stepped off the boat with only the clothes on his body, and an affluent member of the upper-middle class who stained his neckties at the best restaurants across Europe.

I entertained SS officers at the train station in the city of my birth, smuggled frozen horsemeat into a cellar in the ghetto, was sent at the age of seventeen to serve in the army of a country I was not familiar with under the command of officers who spoke a language I understood not a word of. In the service of said country, I was invited to the White House, 10 Downing Street, the lyse Palace, Beijings Forbidden City and Rashtrapati Bhavan in New Delhi. I lunched with Barack Obama, drank coffee with Yassir Arafat, raised a glass with Nicolas Sarkozy, marched in Winston Churchills funeral procession, toured the Third World with David Ben Gurion, and yet my mother thought I had not amounted to much.

I lived my life with guilt-free passion the way only a person who has been spared certain death can. Long-legged girls shook their shapely bottoms for me from the Lido in Paris to the Mirage in Las Vegas. Louis Armstrong played for me, Ella Fitzgerald and Israeli singer Rita Yahan-Farouz sang for me, I presented an award at the German Oscars along with a dead-drunk Jack Nicholson, Danny Kaye was an usher at my wedding, I helped Jackie Mason with his gas mask during a rocket attack on Tel Aviv at the height of the Gulf War. I was an auto mechanic, a lawyer, a journalist, a businessman, a politician and once again a journalist. I wrote successful books of humour and travel guides, my collected essays were bestsellers just like my cookbook, and my comedies were big hits in the national theatre, though everyone including me agreed that my wife was a better writer than me.

I disappointed Menahem Begin, I had a complex father-son relationship with Ariel Sharon, I shouted at Ehud Barak, Binyamin Netanyahu claims to this very day that without me he would not have been able to carry out the financial revolution that saved the country, and Ehud Olmert one of my two best friends in the world sat at my bedside and watched me die. Watched and bawled.

And I ate endlessly: Hungarian sausages, flaky French baguettes fresh from the boulangerie oven, pungent Dutch cheeses, steaming bowls of hummus with beans in Abu Ghosh, thick beef stews in North America, cream cakes in Vienna, wieners as thick as the arms of whichever Gretchen made them in Berlin, sushi in Japan, chicken tikka in Bombay; once I drank a frightful wine in Burma only to discover, too late, that it had been fermented in pitchers in which monkey foetuses had been placed in order to improve the taste. I ate everything, I ate more than everyone, and I always remained hungry.

But still I need to explain this strange act by no means the strangest thing I have ever been involved in that allows a man to write his autobiography after his death. Carlo Goldoni, the eighteenth-century Italian playwright whose most famous work is Servant of Two Masters, once wrote, He only half dies who leaves an image of himself in his sons.

I am writing now through my son, Yair, but my voice has commandeered his own, just as it did more than once during my lifetime. Is this unfair to him, an injustice? I suppose so. But it is not the first injustice I have committed on him and yet he still loves me in that unswerving and occasionally undiscerning way of children who are willing to accept the image we have created for them.

Without his knowing it, I had been preparing Yair for this moment from the day he was born. I told him the story of my life again and again. As with every good storyteller (and what Hungarian Jew is not a good storyteller?) I studded my stories with anecdotes, ridiculous characters, good guys and bad guys, eternal winners and losers, vistas and flavours and scents, and clever and sometimes cruel observations about human nature and its weaknesses.

And Yair always listened. He was a sad and serious boy, nearly friendless, and I filled the emptiness in his life with exhilaration without ever asking myself whether I was the one who had created that emptiness in the first place. I can picture a scene, toward the end of the 1960s, when we had returned to Israel from London with a new record collection and I sat in my small study in Yad Eliyahu listening to Mozarts Magic Flute and enthusiastically conducting my battered stereo system with my chubby, white fingers (a part of my body I always hated). It took me a few minutes to notice that he was there, sitting on the floor and imitating me, conducting a piece he had never heard with the fingers of a child. At that moment I suspected and continued to suspect for years that that imitation would perpetuate itself and, like many children of successful people, he would become the Sancho Panza of my memories without bothering to develop an identity of his own. I was wrong, of course, but let it be said to my credit that I was happy to be wrong.

Death is a very centring moment. It places before you only the most important matters: parenting, family, love. When I look back on these all I have no regrets. Regret is not circumstantial, it is a character trait, and I admit that it does not exist in me. Time and again I said to my kids, The proof of the cooking is in the pudding. If the pudding does not turn out well, no amount of talking about it is going to improve it. And if it does turn out well then the chef deserves an ovation. I had three successful children, and two of them have outlived me. Something was apparently working well in my kitchen.

Next page