Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC 29403

www.historypress.net

Copyright 2015 by John DeFerrari

All rights reserved

First published 2015

e-book edition 2015

ISBN 978.1.62585.619.7

Library of Congress Control Number: 2015945064

print edition ISBN 978.1.46711.883.5

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

This book, once again, is for Sue.

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

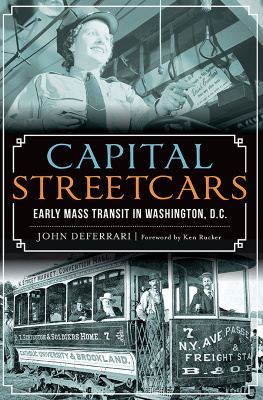

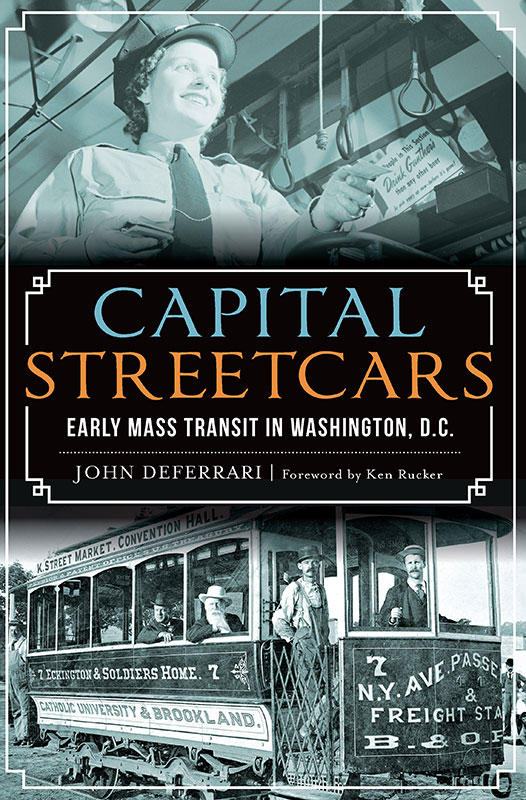

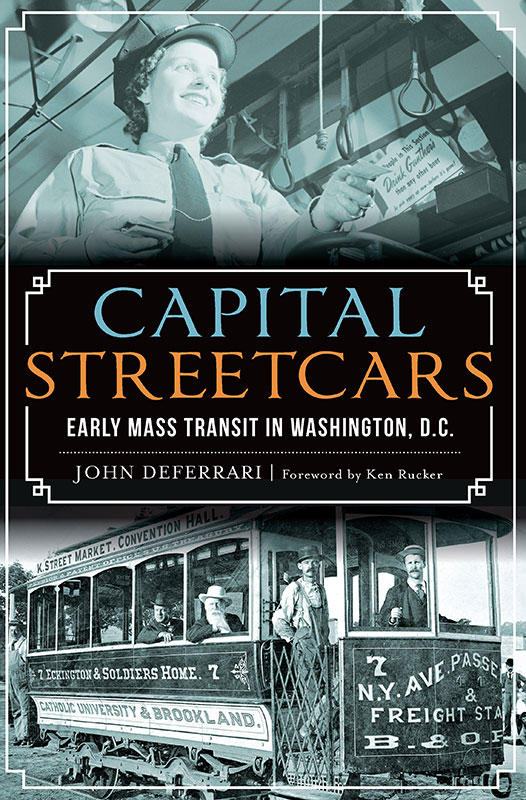

There was a time when folks rode the rails through the streets of Washington. Beginning during the Lincoln administration in 1862, streetcars carried people around the city. For one hundred years, from Lincoln to Kennedy, streetcars connected the communities of the federal city and enabled the development of communities in the county of Washington. First with horse traction, then cable traction and, lastly, electric traction, the streetcars provided what a 1902 census report called an imperative social need by spreading growing urban populations over a much wider area than would have been possible without ever-faster and cleaner street railways. By the 1930s, gasoline-powered buses were providing more flexible transit services, and the automobile beckoned commuters with private, on-demand transportation. After World War II, prosperity accelerated the abandonment of street railways and the expansion of the suburbs served by massive highway development. Sixty years on, many people are looking to urban areas for homes to relieve themselves from long commutes on crowded highways, and revitalization of older communities is welcoming the return of streetcars as symbols of urban renaissance.

Prior histories have chronicled the era of street railways in the nations capital for the traction or railway fan. Now, Capital Streetcars: Early Mass Transit in Washington, D.C. addresses a larger audience as it explores the economic and social needs met by these railways as well. With vignettes establishing the social and political contexts influencing the actions of the characters who made the development decisions, as well as carefully selected images, this work expands the scholarship available beyond the nuts and bolts of railway construction and management to include the social fabric of life in Washington through the streetcar era.

KEN RUCKER

President, National Capital Trolley Museum

May 2015

PREFACE

The streetcar decided where we could live and where we would shop. It gave shape to the city.

Jack Eisen, Washington Post, January 28, 1962

Streetcars had a powerful hold on Washingtonians during their one-hundred-year reign, profoundly shaping the patterns of our lives and the city around us. Where the streetcar went, so went the citys residents. Along with them came the neighborhood groceries, the dress shops and hardware stores, the mom and pop cafs and restaurantsall the fixtures of our urban existence, strung out along the lengths of their routes. And it was on the streetcars that so many lives intersected. In their heyday, virtually everyone rode them. From day laborers to Supreme Court justices, the cars brought Washingtonians together like nothing else ever had.

At times, they could be tremendous fun. Several generations of small boys delighted in stealing rides downtown or in causing mischief by setting blasting caps on the rails or jamming the slot rail in the center of the tracks. As one of the capital citys cheapest forms of entertainment, the much-loved open-air cars of the early twentieth century took thousands of riders on airy jaunts to see baseball games at Griffith Stadium or out across the countryside of Maryland and upper Northwest D.C. To this day, many Washingtonians recall with special fondness riding the Cabin John streetcar out to Glen Echo Park on pleasant summer weekends. Those were experiences of a time and place that will never return.

Most of the time streetcar rides were far from thrilling. For thousands of commuters, they were merely a practical means of getting from point A to point B. They were often crowded, poorly timed and frustratingly slow. Although integrated by federal law since 1864, streetcars were also a flashpoint in the struggle against discrimination in the early twentieth century. During the dark days of the 1919 riots, African Americans, who depended on the streetcars for transportation as much as everyone else, might have feared for their very lives when stepping aboard.

The cars had an impact on almost everyones life, and much of the drama of their story comes from all the change they brought. In the mid-nineteenth century, when streetcars were first proposed, many older Washingtonians were upset at the idea of laying railroad tracks down the middle of Pennsylvania Avenue, splitting the north half of the street from the south. It seemed an outrage. More angst came with the arrival of cars powered by overhead trolley wires, a technology so offensive that it was banned in the downtown part of the city. And not long after that controversy was finally settled, the whole concept of a railed streetcar system was questioned again when automobiles and buses arrived. Technological change fed constant upheaval.

And yet the transportation wants and needs of most people changed little during this time. They wanted streetcars to be easy to access from their homes, to run on convenient schedules, to be reasonably comfortable to ride, to take passengers to their destinations quickly and efficiently and to be inexpensive to use on a daily basis. In many ways, the history of Washingtons mass transit system, like that of others across the country, is the story of an unending struggle to achieve these confounding, elusive goals. It is also the story of the owners and operators, a long line of local transit barons who were all convinced that they could wring profits from the system one way or another. Few of them ever fully succeeded.

The trials and tribulations of streetcars, and the joys and frustrations of riding them, were part of everyday life for hometown Washingtonians of the past. My hope is that this book can help readers paint for themselves a fuller picture of that past life.

WHAT THIS BOOK ISNT

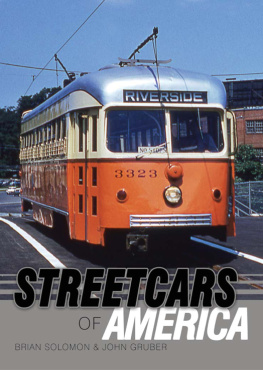

Capital Streetcars is not the first book about the history of streetcars in the District of Columbia. Two impressive, lavishly illustrated books on the same subject have previously been published: LeRoy O. Kings Jr.s 100 Years of Capital Traction: The Story of Streetcars in the Nations Capital (1972) and Peter C. Kohlers Capital Transit: Washingtons Street Cars: The Final Era, 19331962 (2001). These two encyclopedic reference works provide a wealth of detail about the citys vast streetcar infrastructure and how it was managed and operated, including precise route locations, schedules and the numbers and types of rolling stock that served them. King, whose father worked for the Capital Traction Company, amassed an extraordinary collection of images and documentation that detailed the operations of the citys many historic streetcar companies. Kohlers book offers an extensive year-by-year review of all the important events that occurred in the Capital Transit Companys history, from its inception in 1933 to the last streetcar trip in 1962. I highly recommend both books and certainly do not aim to compete with either.

Next page