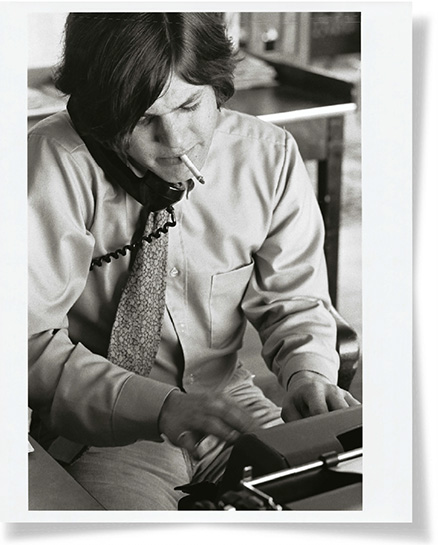

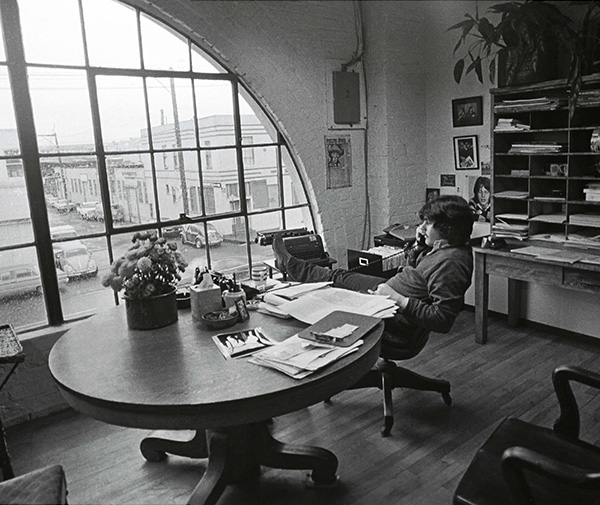

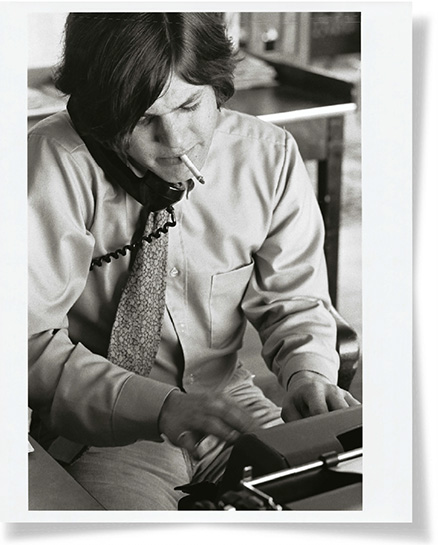

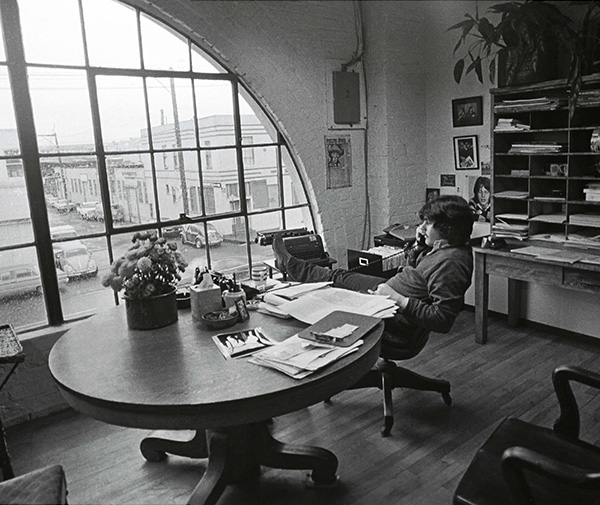

Jann S. Wenner, 1968.

DEDICATION

For the poets of rock & roll, the great singers, songwriters and performers who gave us a new American art, an understanding of ourselves and our world, and for me, a life of music, fun and inspiration.

For the many people colleagues and friends who have traveled and are still traveling the long and winding road. This was something that could not have been done alone.

And for my family, who have shared the ride with me at Rolling Stone. Love you all madly: Jane and Matt, Alex, Theo, Gus, Noah, India and Jude.

Introduction

By Jann S. Wenner

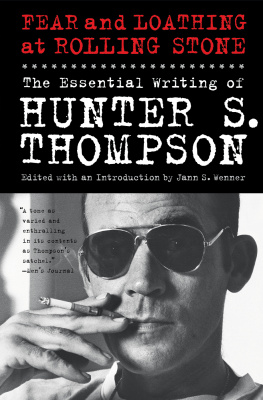

The idea for starting ROLLING STONE came when I was 21 years old and I couldnt find a full-time job. My brief run as the entertainment editor of a local alternative newspaper, Sunday Ramparts, had just ended when the paper folded. That gig had given me a perch in the small world of rock & roll in San Francisco, going to concerts, writing reviews and hanging out with the likes of the Grateful Dead, the Airplane, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison.

It was 1967, the Summer of Love. What a time to be 21 and footloose in a beautiful city bursting with music. The counterculture was thriving in neighborhoods all over town, and there was a very liberal attitude toward drugs. I didnt live in, nor much visit, the Haight-Ashbury. But I went to the Monterey Pop festival, heard the Who and Jimi Hendrix for the first time, met great musicians and slept on the floor at the Blue Cheer house. That summer, Sgt. Peppers was released. I got an advance tape and was commissioned to review it by High Fidelity magazine. My piece was rejected for being too hyperbolic. So much for freelancing.

The man who had gotten me the job at Ramparts, a terrifically smart and passionate music fan, was the San Francisco Chronicles jazz/pop critic, Ralph J. Gleason. Just turning 50, he was, to me, the voice of wisdom. He had a big droopy mustache, a trenchcoat and a Sherlock Holmes hat, and was always smoking a pipe. He had been my friend and mentor since I was a student at UC Berkeley, so I went to him with some thoughts on what I could do to earn a living.

The idea that clicked was a rock & roll newspaper.

Ralph had written a long essay for The American Scholar, a kind of personal manifesto and philosophical survey of the cultural and popular-music landscape the beatniks, anti-war politics, Bob Dylan, the Beatles, campus protest in short, the flowering of what we now call the Sixties. The piece laid out the intellectual framework for what I was thinking about it explained the passion I had found in the music and myself, and the kinds of things I was discovering about the world I was growing up in.

Ralphs essay was titled Like a Rolling Stone, which, of course, came from Dylans song, and thats how we got the name. And in choosing that name, there was also an explicit nod to the Rolling Stones, who, with Bob and the Beatles, were my heroes.

I thought rock & roll needed a voice a journalistic voice, a critical voice, an insiders voice, an evangelical voice to represent how serious and important the music and musical culture had become, in addition to all its manifest entertainment value; a place where fans and musicians could talk to one another, get praise, advice, feedback; someplace we could shout, Hail, hail rock & roll, deliver us from the days of old.

Founder Jann S. Wenner at his desk in ROLLING STONES original offices, at 746 Brannan St. in San Francisco.

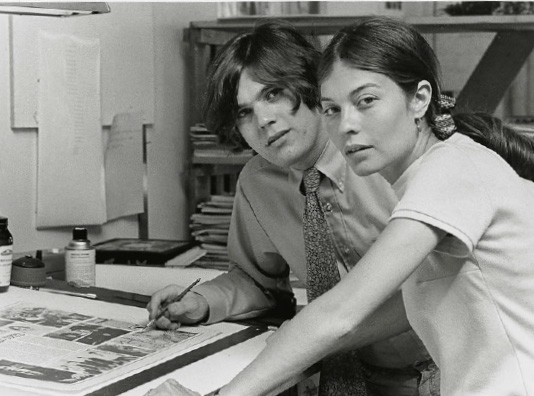

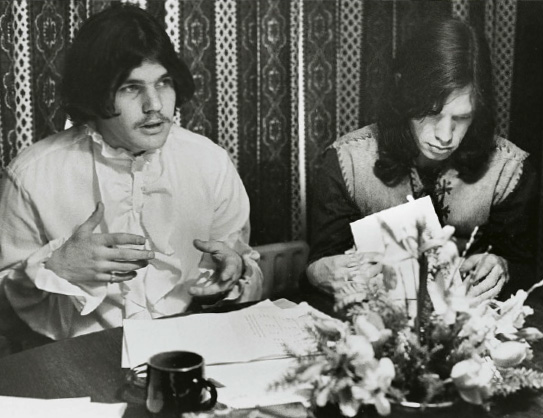

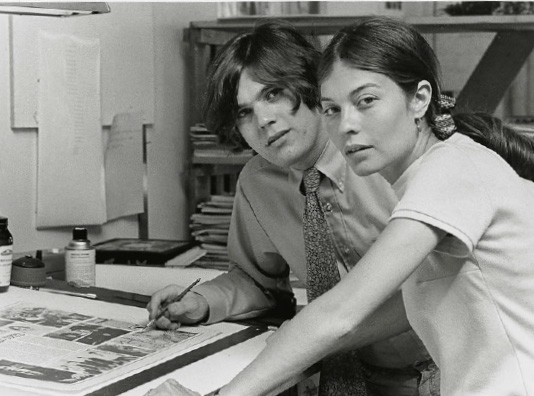

Wenner and Jane Schindelheim working on an early issue at the first ROLLING STONE office in San Francisco. They married less than a year after the magazine was launched.

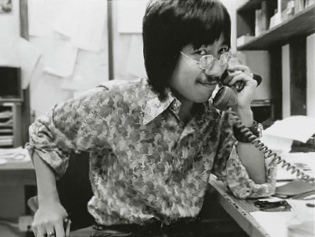

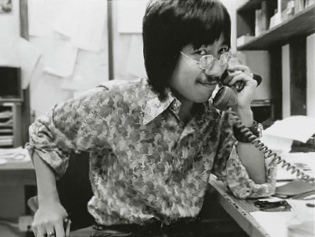

Ben Fong-Torres, senior editor from 1969 to 1981, wrote features on Marvin Gaye, Linda Ronstadt and more.

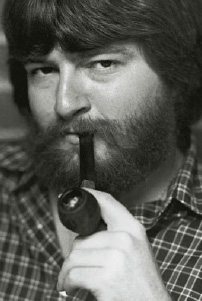

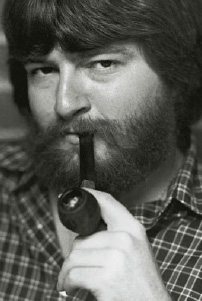

Joe Eszterhas, who wrote landmark investigative pieces before moving on to screenplays, including Basic Instinct.

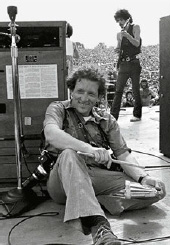

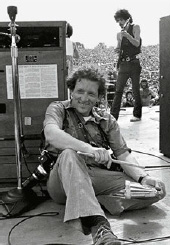

Former chief photographer Baron Wolman shooting Santana at Woodstock.

John Lennon and ROLLING STONE co-founder Ralph Gleason at the Beatles final show, at Candlestick Park in 1966.

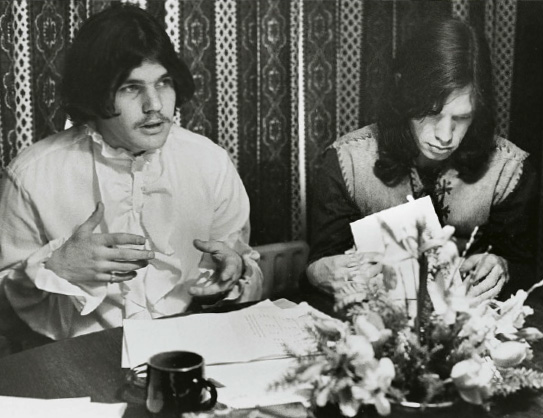

Wenner and Mick Jagger announcing their partnership for the British edition of ROLLING STONE in London, 1969. Jagger was the subject of one of Rolling Stones first long-form interviews.

Music was the glue holding a new generation together. Rock & roll was the tribal telegraph, and the only places you could get it were on the radio, in a record store or on the jukeboxes. It wasnt just great music, great songs and great singers; rock & roll was also cultural and political upheaval, freedom from drug and sexual and social repression. It was the post-World War II baby boom coming of age and determined to have its way... and then came Rolling Stone, the little biweekly newspaper from San Francisco.

In the editors note for the first issue, I wrote, We have begun a new publication reflecting what we see are the changes in rock and roll and the changes related to rock and roll.... We hope that we have something here for the artists and the industry and every person who believes in the magic that can set you free. Rolling Stone is not just about music but also about the things and attitudes that the music embraces.

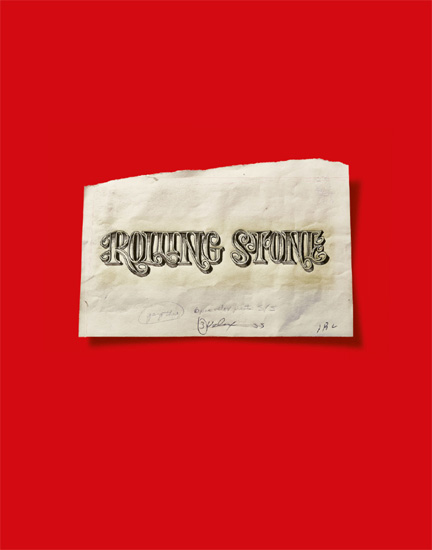

I got together $7,500 from a few friends, arranged for free office space in the warehouse of our first printer, and scored some used filing cabinets and typewriters. Our logo was hand-drawn by my favorite poster artist, Rick Griffin. And with a few friends from my Berkeley days, and my then-girlfriend, Janie Schindelheim, and her sister all volunteering we got that first issue rolling off the tiny rotary press that had once printed Sunday Ramparts and The Peoples Weekly World.

We opened champagne as we watched the first issues being printed. The next day, we began sending copies to every musician we could get an address for and to all of Ralphs friends in the music business in hopes of advertising support (Ralph stayed deeply involved with us until he died in 1975). And we got it $100 for a full-page ad for a Captain Beefheart record. And then came letters of appreciation from musicians the very first from Rolling Stones drummer Charlie Watts.

Next page