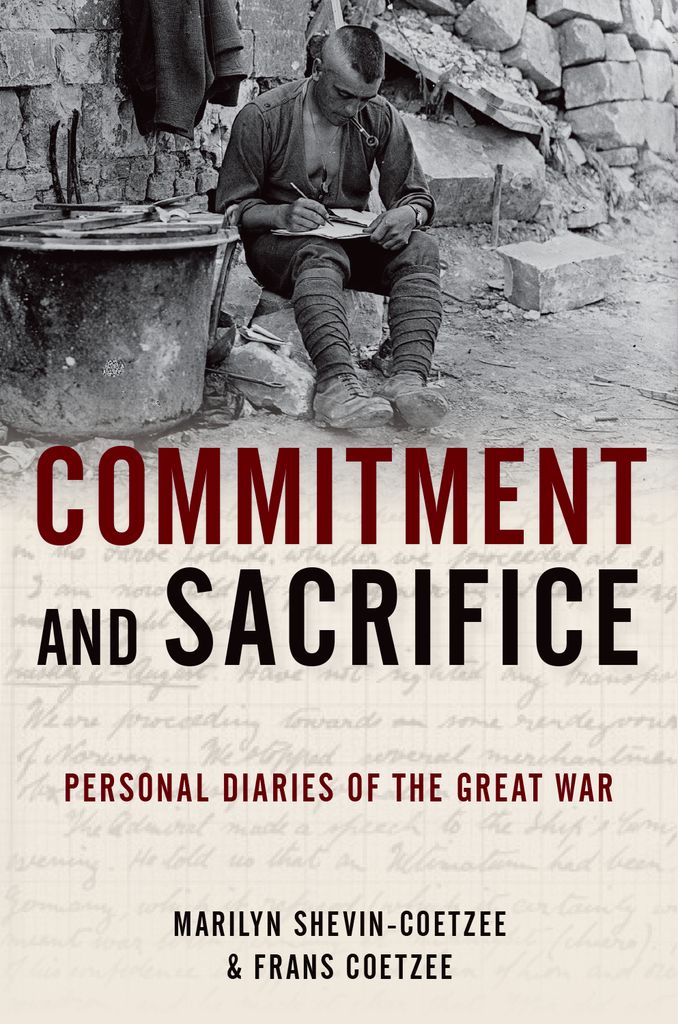

Commitment and Sacrifice

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

OxfordNew York

AucklandCape TownDar es SalaamHong KongKarachi

Kuala LumpurMadridMelbourneMexico CityNairobi

New DelhiShanghaiTaipeiToronto

With offices in

ArgentinaAustriaBrazilChileCzech RepublicFranceGreece

GuatemalaHungaryItalyJapanPolandPortugalSingapore

South KoreaSwitzerlandThailandTurkeyUkraineVietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Commitment and sacrifice : personal diaries from the Great War / Marilyn Shevin-Coetzee & Frans Coetzee.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199336074 (hardback : alk. paper)eISBN 97801993360981. World War, 19141918Personal narratives. 2. World War, 19141918Sources. 3. War diaries. I. Coetzee, Marilyn Shevin, 1955 II. Coetzee, Frans, 1955- D640.A2C65 2015

940.481dc23

2014041488

This book is dedicated to our daughter, Michelle.

CONTENTS

John French, British sapper

Phillip T. Cate, American ambulance driver

Willy Wolff, German internee in Britain

James D. Hutchison, ANZAC artilleryman

Henri Desagneaux, French infantry officer

Felix Kaufmann, German POW in France

Philip T. Catediary (RG1/007) courtesy of the Archives of the American Field Service and AFS Intercultural Programs.

Henri Desagneaux,A French Soldiers War Diary, 1914-1918. Edited by Jean Desagneaux, translated by Godfrey J. Adams. Morley, Yorkshire: Elmfield Press, 1975.

Sapper John T. French Diary. Redruth Old Cornwall Society Museum, Redruth, UK.

Sir James D.Hutchison Diaries, MS-Papers-4172. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.

Felix KaufmannDiary. ME 233. M44. Leo Baeck Institute, New York, New York.

Willie Wolffdiary, 19141919, Willie Wolff Papers, Louisiana Research Collection

Tulane University. Translated from the German by Marilyn Shevin-Coetzee.

This book brings to light the previously unpublished diaries of five participants in the First World War and restores to publication much of the diary of a sixth that has long been out of print. The six diarists are a diverse group with varied experiences. John French was a Cornish tin miner who served as a sapper in the British Army, tunneling underground toward German lines in Belgium and northern France to place explosives from January 1916 onward. Philip T. Cate was an idealistic American volunteer who went abroad not to fight but to heal, driving ambulances in the mountainous Vosges sector of eastern France in 191516. Willy Wolff, a German-born cotton broker in the Manchester office of a Rhenish textile firm, was arrested in October 1914 by the British and interned as an enemy alien until his release in 1919. New Zealand artilleryman James Douglas Hutchison, having volunteered in the first week of the war only to be rejected as too young, reapplied and formed part of the famous ANZAC contingent dispatched to Gallipoli in 1915. Invalided home, he returned to active service in 1918 on the western front. Henri Desagneaux, whose diary appeared briefly in print after his death in 1969, was a French infantry officer frequently in the thick of the bloodiest fighting whose experiences spanned the rush to the colors of August 1914 to eventual demobilization in 1919. Felix Kaufmann, who served as a machine-gunner in a German infantry unit, was captured in 1917 and endured confinement as a French prisoner of war until 1920.

The diaries that these six men found the opportunity, the will, and the necessary materials to write illuminate what might be called the intimate history of the war. Initially, it was the great collections of diplomatic documents, reports of stirring speeches, and the partisan memoirs of the leading participants that shaped analysis of the conflict. Grundys prediction was apt, even if it has taken somewhat longer than he anticipated for the social and cultural history of the conflict to displace scholars initial focus upon the wars diplomatic and strategic outlines. Yet now, a century later, shedding a more intimate light on 191418 by emphasizing the experiences of ordinary individuals is at the forefront of historians approaches to the Great War.

Intimate histories of the war have taken several forms. First, there are the broad overviews. Svetlana Palmers and Sarah Williss The authors desire to achieve comprehensive coverage, however, necessitates a reliance on brief quotations and frequent, rapid shifts from one source to another. In achieving breadth, they almost inevitably sacrifice depth.

A second approach is to focus on single combatants, reproducing either their diaries or their correspondence from the front. These sorts of publications are staggering in quantity, though highly variable in quality. Perhaps the most remarkable recent addition to this individual-soldier genre is Martha Hannas sensitive exploration of the voluminous correspondence (perhaps 2,000 letters over four years) between a French soldier, Paul Pireaud, and his wife, Marie, who sought to cope with the demands of an infant son and the family farm in the Dordogne. She illustrates, as few historians have, the importance of regular correspondence in sustaining personal relationships under the severe wartime strain of enforced separation and omnipresent danger. The written word, Hanna reminds us, underwrote the French war effort, as the nations perhaps first fully literate generation produced some 4 million letters per day and several billion over the course of the conflict.as the Duke of Wellington is alleged to have intimated, the Battle of Waterloo had been won on the aristocratic playing fields of Eton, then a case might be made that Verdun and the Marne (twice) had been won (or those campaigns sustained) in the republican classrooms of French primary schools.

Nonetheless, collections of wartime letters, however revealing, raise issues as historical sources. In many cases it may be difficult to ascertain how complete a run of correspondence might be. Not only are individual letters easily weeded from a collection, but the sheer difficulty involved in delivering so much mail, from soldiers often on the move or in precarious circumstances, suggests that what correspondence survives is often fragmentary. More significantly, the military authoritiesand not just in Franceimposed censorship on military correspondence. Postal censors were employed to comb selected samples to ensure that soldiers did not unwittingly divulge military secrets (such as their location, operational plans, or casualties) or openly prejudice the war effort (by relating criticisms of officers, instances of defeatism, poor morale, or sympathy with the enemy). Soldiers knew that their letters home might be intercepted and read, so it is not unlikely that on occasion correspondents exercised self-censorship, avoiding either the specific details or controversial opinions that might run afoul of the censors.