Chapter 1

Equality

The ambition of the Lincolns

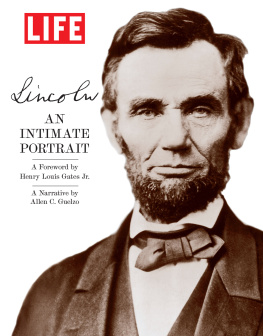

Abraham Lincolns forebears arrived in the New World in the 1630s, in the first great wave of English migration across the north Atlantic. The Lincolns had been a family of middling gentry in Norfolk, a county whose flat fenlands were a hotbed of Puritan religious dissent from the Church of England. But in the 1630s, official repression of Puritanism became increasingly violent, and the Puritans underground leadership finally turned to the desperate expedient of setting up a commercial corporation on the shores of the little-known Massachusetts Bay to serve as a cover for a mass Puritan exit from England. Among the Norfolk Puritans who signed up with the Massachusetts Bay Company were three of the Lincolns from the Norfolk town of Hingham. One of them, Samuel, an eighteen-year-old weavers apprentice, settled himself in a new Hingham, south of the principal Massachusetts settlement of Boston.

It is not certain that Samuel Lincoln was actually emigrating in pursuit of pure religion. Samuel Lincolns father, Edward, had been kicked down the social ladder in 1620 when his own father left him only a pittance of the Lincoln property in Norfolk, and Edwards sons were reduced to service as weavers apprentices. When the Puritan exodus to Massachusetts began a decade later, it represented as much an opportunity to recoup the lost Lincoln fortunes as it did to escape the inquisitorial curiosity of the established Church of England. Land was cheap in Massachusetts, unencumbered by entails and quit-rents, and required only a strong back to clear it. By 1649, the weavers apprentice from the old Hingham had acquired his own land-holding in the new Hingham, joined Hinghams reformed church, and married, thus securing at once advantages earthly and heavenly, which he could never have inherited in England.

There was something in Samuel Lincolns restless search for independence and prosperity that seemed to have stamped itself onto the Lincoln family character. Samuels fourth son, Mordecai, carved out a new Lincoln domain in neighboring Cohasset, which included three mills and an iron furnace, worth more than 3,000. Samuel Lincolns grandsons, Mordecai and Abraham, moved yet again, and by the 1730s acquired hundreds of acres in northern New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. Yet another generation brought the descendants of Samuel Lincoln to the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, where they contracted marriages into the first families of the valley and moved into the front rank of Shenandoah landowners. Finally in 1782, yet another Abraham Lincoln, deciding that his 260 acres of prime Shenandoah farmland was still inadequate to slake the Lincoln thirst, propelled himself over the Appalachians to stake out as many as 2,000 acres of virgin Kentucky forestland.

It was there, however, that the spectacular and acquisitive rise of the Lincolns came to a halt. Sometime in 1785 or 1786, while clearing ground near the settlement of Hughes Station, Abraham Lincoln was ambushed and killed by a party of marauding Shawnee Indians. The story of Abraham Lincolns murder was handed down vividly to every Lincoln thereafter: how Abraham had been shot down by a Shawnee while laying up fence rails, how the Shawnee marauder had snatched up Abrahams eight-year-old son Thomas as a prize, how Thomass fourteen-year-old brother Mordecai had picked up his fathers rifle and, taking aim at a Silver ornament or medal on the Indians chest, shot the Indian dead.

It was a heroic story. (In fact, more than just creating a story, it fostered a pathological hatred of Indians in Mordecai Lincoln, who in later years was rumored to have indulged more than a little revenge-killing, for the Indians had killed his father and he was determined to have satisfaction.) But heroism aside, the death of Abraham Lincoln was the most serious setback for any of the Lincolns since the disinheritance of Edward Lincoln a century and a half before, and not only for the loss of the head of the household. Kentucky, in the 1780s, was still a province of the state of Virginia, and governed by Virginias laws of inheritance. The bulk of the property left over after sales and taxes went to young Mordecai; nothing went to Thomas Lincoln or his two siblings. So instead of the Kentucky migration opening up a new chapter in the expanding story of the Lincoln family, young Thomas Lincoln found himself at age sixteen right back where his ancestor Samuel had been in 1637, an apprentice, this time as a cabinet maker.

And a cabinet maker he might easily have remained, for there was something in the ancestral passion of the Lincolns for self-improvement that never seemed to have fired in Thomas Lincoln. His neighbors remembered him as lazy & worthless... an excellent specimen of poor white trash who could barely read and write, a piddler who was always doing but doing nothing great. Years later, one of Lincolns friends, Ward Hill Lamon, would characterize Thomas Lincoln as apparently the most shiftless of men, an unskilled carpenter, a careless farmer, a wanderer over the face of the earth, but, wherever he went, taking with him his proverbial bad luck. It was not that Thomas Lincoln was entirely immune to his forebears restless pursuit of greener, or at least more plentiful, pastures. As early as 1803 (and probably with help from his brother Mordecai), he purchased a small plot of land north of Elizabethtown, Kentucky. In 1806 he married Nancy Hanks, and in February of 1807, the Lincolns first child, a daughter, Sarah, was born. Thomas evidently decided to let cabinet making be a sideline after her birth and moved the family to small farm on Nolin Creek, near Hodgenville, Kentucky, to take up farming where his father had left off fourteen years before. And it was there, on February 12, 1809, that a son was born. And perhaps with consciousness that he was trying to pick up the threads of a livelihood that the Indians had cut short with his own fathers death, Thomas Lincoln named the boy for his grandfather, Abraham Lincoln.

But try as he might, Thomas Lincoln was spectacularly unsuccessful in reconnecting to the ambitions of his Lincoln ancestors. White settlement of Kentucky had been originally managed by a land speculation outfit, the Transylvania Company, which undertook a haphazard series of land surveys in order to begin selling prime acreage to land-hungry Virginians like the Lincolns. (In the four miles surrounding the new settlement of Harrodsburg, hasty surveying created parcels of land in every imaginable shape known to Euclidean geometry.) By the time Thomass son was born, Kentucky land titles were riddled with enough cross-claims and defective titles to keep a stateful of lawyers in business. Among those defective titles was Thomas Lincolns. The Hodgenville farm turned out to have a lien against it from an earlier owner, and Thomas lost the property; he bought a smaller farm on Knob Creek, in the same county, but in 1815 a neighboring landowner claimed to title to the Lincoln property, and Thomas found himself embroiled in another suit to protect his land.

He eventually won that suit, but the winning seemed scarcely worth it. The Knob Creek farm was difficult land to make a living from. Half a century later, Abraham Lincoln would remember that this farm lay in a valley surrounded by high hills and deep gorges, and on one occasion, after planting corn and pumpkins, a big rain in the hills flooded the valley and washed ground, corn, pumpkin seeds and all clear off the field. It did not help, either, that Kentucky farming was increasingly becoming dominated by large-scale plantations that used the labor of black slaves to raise crops. Against big-time competition like that, a small farmer like Thomas Lincoln stood little chance for carving out any lasting commercial success.

Thomas Lincolns solution to his problems was the classic Lincoln gambit: move again, this time to Indiana, where the federal government, under the terms of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, had not only laid out secure land surveys that guaranteed secure titles but also banned the import of slave labor. In 1816 Thomas Lincoln gathered up his small family again and migrated north, across the Ohio River, to the thick forests of southwestern Indiana, where he had filed claim to a 160-acre quarter-section of Congress land, for which he made a down payment of sixteen dollars. But even this time-tried resolution for the Lincolns troubles seemed not to work for Thomas Lincoln. A second son, named Thomas for his father, was born but died within three days. In October 1818, Nancy Hanks Lincoln developed the milk sickness, from drinking the milk of cows that had grazed on the poison white-snakeroot plant, and died. Thomas remarried in December, 1819, and it was his one stroke of good fortune that his new wife, a widow named Sarah Bush Johnston. with three children of her own, turned into the perfect nurturer for the two motherless Lincoln children. She was a woman of great energy, of remarkable good sense, very industrious, wrote her grandson-in-law, August Chapman, She took an especial liking to young Abe. Her love for him was warmly returned & continued to the day of his death.... Few children loved their parents as he loved this Step Mother.