David Park, Painter

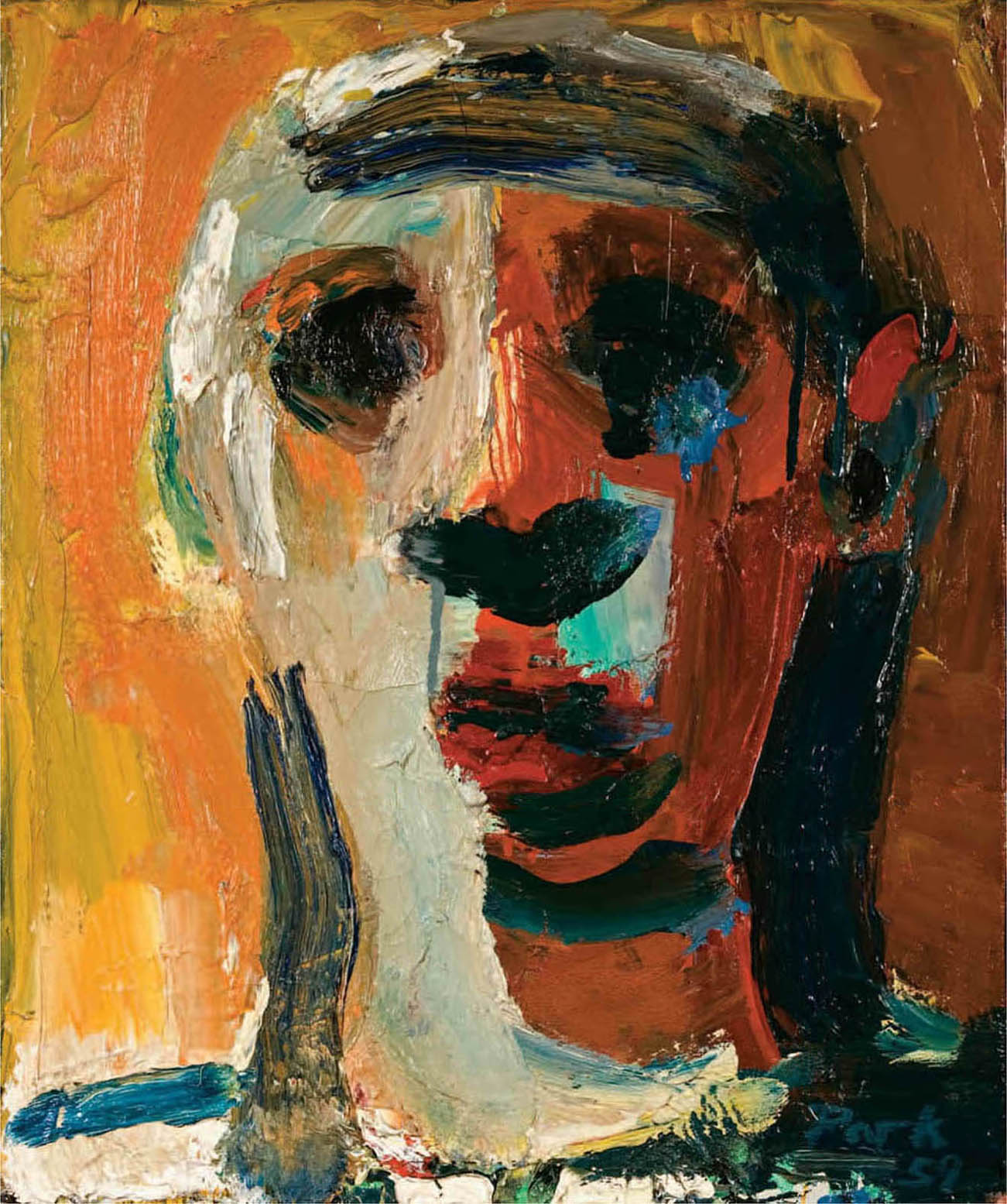

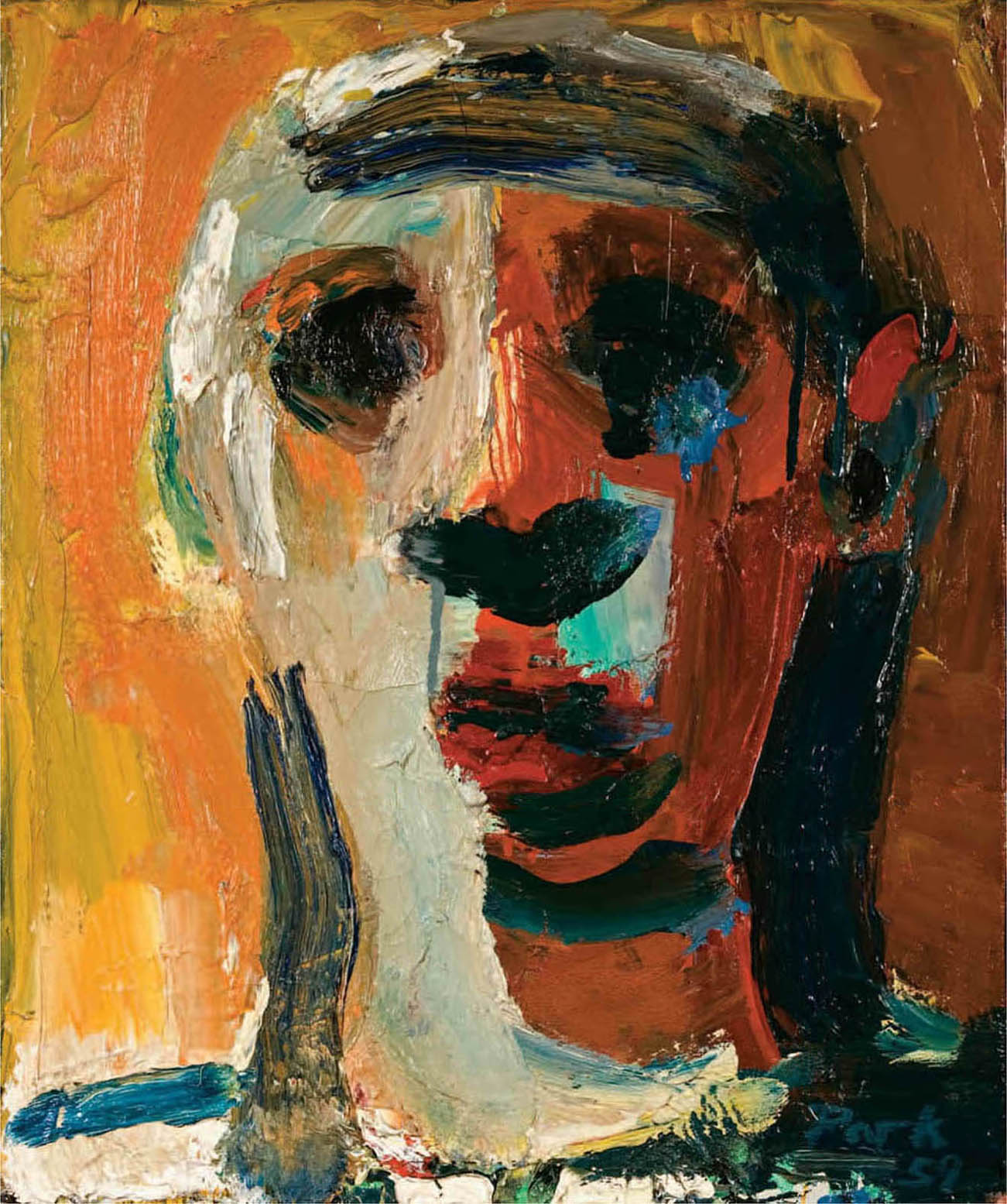

Head, 1959 Oil on canvas, 19 16in. (43.8 40.6 cm.) Collection of Ken and Barbara Oshman

For all of my family, and especially for my sister, Natalie Park Schutz

Copyright 2009 Helen Park Bigelow

All images by David Park The Estate of David Park

First published by Hudson Hills Press LLC 2009

First Counterpoint edition 2015

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Previously published material, adapted for this book and used with permission, has appeared in The Monthly: The East Bays Premier Magazine of Culture and Commerce, June 1998; The San Francisco Examiner Magazine, September 21, 1997; House Beautiful Magazine, March 1994; The Palo Alto Cultural Center Members Newsletter, Winter 1994; and The Museum of California Magazine, JulyAugust 1989.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bigelow, Helen Park.

David Park, painter: nothing held back / Helen Park Bigelow; foreword by Richard Armstrong. 1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Park, David, 1911-1960. 2. PaintersUnited StatesBiography. I. Park, David, 1911-1960. II. Title. III. Title: Nothing held back.

ND237.P24B54 2009

759.13dc22

[B]

2009013963

Design: David Skolkin: Skolkin + Chickey, Santa Fe, NM

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

e-book ISBN 978-1-61902-671-1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Guide

CONTENTS

by Richard Armstrong

W E VORACIOUS VIEWERS, COLLECTORS, and partisans of art too often forget that before we encounter a museums taxonomic and chronologically precise display of paintings and sculpture, those works of art existed in the studio as messy, complicated, sometimes contradictory extensions of one personthe artist. Who better knows that person than his or her family? In these poignant and illuminating recollections of her father, painter David Park, Helen Park Bigelow gives us multiple views of a man and his evolving work. David Parks brief but intense production as a mature artist adds urgency to her mission to recall and reflect on the progenitor of what came to be known as Bay Area Figurative painting.

One of the few stylistic alternatives to 1950s Abstract Expressionism, Parks heritage of figuration has remained influential in the decades since his death in 1960. Less explored but of comparable import is an explanation of how a provincial artists work came to center stage and remained there, how his transformation from a transplanted Yankee who came of age in Social Realist San Francisco to a world-class painter could and did transpire. How that happened, at what price, and why, are mesmerizingly suggested in Bigelows moving vignettes and important observations.

Our ignorance of the studio process is frequently abetted by ignorance of most artists origins, circumstances, character, and social set. Park was an uncommon but by no means unique example of an American artist who, despite limited access to the work of his days avant-garde, nonetheless lived in the shadow of the likes of Picasso. As a figurative painter, Park in particular was obliged to confront and surmount these protean forebears of his chosen imagery. Ironically, he could do so only after falling under the spell of such abstract masters as Clyfford Still and Robert Motherwell. Their work of the late 1940s defined the parameters of ambitious painting in the San Francisco area, and for a few short years after World War II Park produced his version of Abstract Expressionism. But in 1949 he precipitously abandoned that style and destroyed most of his work of the previous three years. From late 1949 onwards to his death eleven years later, Park pushed representational painting in his quest to capture and enhance his chosen realities. Not long after his turn from abstraction, he wrote about his nonrepresentational work for a small San Francisco-based periodical:

During that time I was concerned with the big ideals like vitality, energy, profundity, warmth. They became my gods. They still are. I disciplined myself rigidly to work in ways I hoped might symbolize those ideals. I still hold to those ideals today, but I realize that those paintings practically never, even vaguely, approximated any achievement of my aims. Quite the opposite: what the paintings told me was I was a hard-working guy who was trying to be important. (The Artists View, no. 6, September 1953)

Typical of his skepticism and congenital inability to be grand, Parks words are poignant. His path epitomizes the ferocious struggle of all gifted American artistsall provincials until the late 1940sto establish an identity. Parks labors had to be especially fierce because of the accidents of his personal geography: going from Boston to San Francisco at a time when neither place had a community of advanced artists. It is a measure of Parks talent and his fundamental certitude that within a short time of moving to San Francisco in 1929 he was at home in the company of the citys best artists, including the visiting Diego Rivera. His luck in colleagues and friends only grew, and Helen Park Bigelow captures many of them in sharp focus, underscoring the crucial importance of life-sustaining camaraderie between like-minded friends and family, as well as its fragility. By the time of his death in 1960, Park and his work were at the forefront of a group of immensely gifted painters, Richard Diebenkorn and Elmer Bischoff not least among them.

Writing about Park in the Whitney Museum of American Arts catalogue for his 1989 retrospective there, I subtitled my piece A Pilgrims Progress. David Parks transformation from his conventional Back Bay origins to becoming one of the standouts of twentieth-century American art is little less than astonishing. Equally astonishing is Americas transformation from its modest artistic heritage to its position today. The penetrating views Helen Park Bigelow offers in this story of her fathers life, times, mores, and values are especially valuable as we persist in seeking to make real and human the commanding artistic figures, now mostly gone, who propelled this American transformation.

RICHARD ARMSTRONG

Director

Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

New York

I MAGINE A BIG, SQUARE, WELL-LIGHTED, MESSY STUDIO with cigarette smoke hanging in the air and blending with the smell of oil paint and turpentine. A window is open to the crisp Berkeley day, and large and small canvases are stacked along the floor against the walls, some with their backs facing you, some three and four deep, one on the easel, a couple hanging on walls, and one propped on an old bookcase. Imagine them all, Daphne and Couple and Four Women and Head and Women in a Landscape and Red Bather (). Paintings like that, those very paintings, paintings all over, and there I am, one of the painters daughters, twenty-six, looking.

Stunned, speechless, heavy, blunted, dazed, as uncomfortable as Id ever been, all my life wanting and trying to feel what my eyes saw, wanting to have words even just for myself, words for sorting it out and saving it. That this was my fathers work. That he did it all and it came from inside of him and it said who he wasthis reality was stunning and left me speechless. Then that the paintings themselves existed and looked the way they did and had the power and depth andwhat was it, magnificence?that they had, making it unimportant who painted them so long as they existedthis was the other reality.