Introduction

The symbolism of boxing does not allow for ambiguity; it is, as amateur middleweight Albert Camus put it, utterly Manichean. The rites of boxing simplify everything. Good and evil, the winner and the loser.

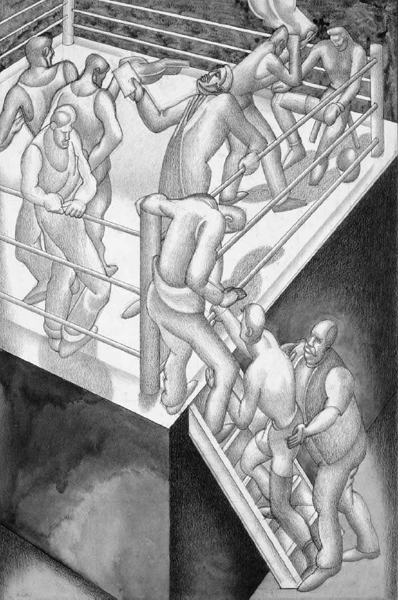

Boxing, it seems, has been around forever. The first evidence of the sport can be found in Mesopotamian stone reliefs from the end of the fourth millennium BC. Since then there has hardly been a time in which young men, and sometimes women, did not raise their gloved or ungloved fists to one other. William Robertss 1914 watercolour The Boxing Match, Novices conveys the relentless succession of contenders, champions and palookas that makes up the history of boxing. Throughout this history, potters, painters, poets, novelists, cartoonists, song-writers, photographers and film-makers have been there to record and make sense of the bruising, bloody confrontation. For some reason, sportswriter Gary Wills remarked, people dont want fighters just to be fighters.

Writing about boxing is often nostalgic, evoking a golden age long since departed. Today the period most keenly remembered is that of the late 1960s and early 70s, a time dominated by Muhammad Ali, a time, as a recent documentary would have it, when we were kings.

Although this book is about boxing in its modern form, myths about the golden ages of classical and Regency boxing have had such a lasting impact on ways of thinking about the sport that I begin with them. The first two chapters chart the early history of boxing and the establishment of ideas about courage and honour, ritual and spectatorship, beauty and the grotesque that are still in use today. The third chapter explores what pugilistic style meant to Regency painters and writers.

The golden age of English boxing was over by 1830. Nevertheless, the sport continued to hold sway over the popular imagination throughout the nineteenth century. Chapter Four considers the divide between (dangerous, illegal) prize fighting and (honourable, muscular Christian) sparring in the Victorian era, and the appeal of each to writers as different as George Eliot and Arthur Conan Doyle. The fin de sicle rise of professional boxing (and its association with the development of mass media such as journalism and cinema in America) is the subject of Chapter Five. Women (welcome participants in the eighteenth century) now re-entered the arenas as spectators. Chapter Six shifts the focus to questions of race and ethnicity, investigating the ways in which boxing was associated with assimilation for young Jewish immigrants and the ways in which black American boxers struggled against the early twentieth-century colour line. The career and enormous cultural impact of Jack Johnson, the first of the twentieth-centurys great black heavyweights, is explored in some detail. Another iconic presence, Jack Dempsey, dominates Chapter Seven. The chapter considers the sports-mad twenties and argues that many of modernisms styles were self-consciously pugilistic.

The final two chapters take us to the end of the twentieth century. Chapter Eight discusses mid-century representations of boxing and the ways in which the sport now featured largely as a metaphor for corruption and endurance that is, until a young fighter called Joe Louis emerged on the scene. Finally, Chapter Nine examines the era of Muhammad Ali, television, Black Power, and further compensatory white hopes. The conclusion brings the story up to date, taking into account, among other matters, Mike Tyson and hip hop, conceptual arts glove fetishism and the enduring appeal of sweaty gyms.

1

The Classical Golden Age

Looking back nostalgically from the third century AD to the glorious athletic past of Classical Greece, Philostratus claimed that the Spartans invented boxing. In both cases, the boxers adopt an attitude similar to that found in Greek vase paintings 1,000 years later. The earliest of Greek literary works, the Iliad and the Odyssey, written in the eighth century BC, describe athletic games held at the time of the Trojan war, traditionally dated around 1200 BC.

The funeral games for Patroclus in the Iliad (c. 750 BC) include the first report of a prize fight in literature.

| 2 Two boxers on a fragment of a Mycenaean pot from Cyprus, c. 13001200 BC. |

The games described in the penultimate book of the Iliad certainly do more than simply provide more entertaining fight scenes. Most commentators read the funeral games for Patroclus as one of the poems representative moments; that is, they encapsulate the issues of honour and reward that the poem usually dramatizes on the battlefield. Prize-giving the nature and function of reward forms the topic of much debate. The boxing contest is preceded by Achilles giving Nestor a two-handled bowl simply as a gift, for now old age has its cruel hold upon him. He accepts it, acknowledging that now it is for younger men to face these trials. The prizes for the boxing match are then set forth: the winner will receive a hard-working mule, signifying endurance, the loser a two-handled cup. Prefiguring the boasts of Muhammad Ali, Epeios claims the prize before any competitor has even stepped forward:

I say I am the greatest... It will certainly be done as I say I will smash right through the mans skin and shatter his bones. And his friends had better gather here ready for his funeral, to carry him away when my fists have broken him.

Finally someone steps forward, Euryalos, another godlike man of noble lineage, though we hear little about him. It seems to be an even match, but Homer presents it in very general terms a flurry of heavy hands meeting, a fearful crunching of jaws, followed by a knockout blow to Euryaloss collarbone. All that matters is that Epeioss boasts are justified he is the greatest (after all, he is also the man who designed the wooden horse). Godlike, he is also described as great-hearted because, despite his threats, he does not kill his opponent, but lifts him to his feet. Symbolic conflict acts as the transition between combat with consequences and combat with none, between narrative complication and closure. It quarantines real violence (the crunching of jaws) by enfolding it between two layers of symbolic violence (the bloodthirsty boast, the raising of the vanquished). Boxing, here, is the ultimate deep play.