BLOOMING FLOWERS

Copyright 2020 Kasia Boddy

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publishers.

For information about this and other Yale University Press publications, please contact:

U.S. Office:

Europe Office:

Set in Adobe Garamond Pro by IDSUK (DataConnection) Ltd

Printed in Great Britain by Gomer Press Ltd, Llandysul, Ceredigion, Wales

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020932727

ISBN 978-0-300-24333-8

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Adele Wirszubska Boddy

and remembering Francis Andrew Boddy

This is a world where there are flowers.

Henry David Thoreau

Contents

Gathering Flowers

In 2012, the North American Journal of Psychology reported that male hitchhikers who carried flowers were more likely to be offered a lift. That makes sense to me. If a man has murder on his mind, he doesnt stop to pick up peonies first. But the researchers thought that something more was at stake, something more positive: we invite people bearing blooms into our cars, they said, because flowers are an inducer of powerful emotions. This book is about those powerful emotions.

Sometimes its a particular combination of colour and form that catches the eye: the dark blue of an agapanthus, the symmetry of a sunflower, the perfect globe of an allium, the elegant spike of a foxglove. Flowers provide us with a continuing aesthetic education, but we also look at them from the vantage point of the education weve already had. Daffodils made D.H. Lawrence think of ruffled birds on their perches; yellow cabs reminded Frederick Seidel of daffodils. John Ruskin brought a fine-tuned sensibility to bear when declaring a bunch of anemones marvellous in their exquisitely nervous trembling and veining of colour violin playing in scarlet on a white ground. James Schuyler, a curator at New Yorks Museum of Modern Art as well as a poet, couldnt get over the beauty that met him at five oclock on the day before March first, 1954, when he saw the green leaves and pink flowers of the tulips on his desk against the backdrop of a setting Manhattan sun.

But its not all looks. Sometimes, its the fragrance: what Francis Bacon called the breath of flowers. A fugitive whiff of jasmine creeping over a neighbours fence; a sudden hit of thyme when we brush against the plant with bare summer feet; the heady inhalation of a musk rose. Sadly, an alluring fragrance is low down on most plant breeders lists. Cultivated flowers are selected for size, colour, and, most of all, durability and suitability as freight. Nevertheless, florists report that the first thing customers do when they enter a store is bend over the blooms in search of scent.

Beyond the sensory hits, we also love flowers because of the density of associations that have grown up around them over the centuries, and that have been passed down to us in legends, histories, proverbs, poems, paintings, and wallpaper prints. Flowers live in our cultures as well as in nature. Girls are named for Lily, Saffron, Poppy, Rose and Daisy, but we also like to joke about a flowers botanical Latin nomenclature. The novelist Eudora Welty belonged to a club of night-blooming-cacti fanciers whose motto was Dont take it cereus, lifes too mysterious.

Flowering plants mark birth, death and almost every significant occasion in between. Its not surprising then that they inhabit our earliest and deepest memories: making daisy chains in the park; being told off for picking next doors tulips; planting sunflower seeds then watching them grow, it seemed, as high as the sky. And the flowers dont even have to be real. For Virginia Woolf, it was anemones, red and purple flowers on a black ground my mothers dress; and she was sitting either in a train or in an omnibus, and I was on her lap. I therefore saw the flowers she was wearing very close; and can still see purple and red and blue, I think, against the black.

Perfumes offer to recreate these kinds of moments, even if the flowers they evoke smell completely different. Creating a perfume called Daisy, Marc Jacobs wanted to evoke a friendly flower, not precious, not exotic but, since daisies dont have much scent, he used jasmine. And jasmine is also an ingredient, along with bergamot and pink pepper, in Acqua di Parmas Sakura, designed to evoke the spectacle (if not the scent) of blossoming cherry trees.

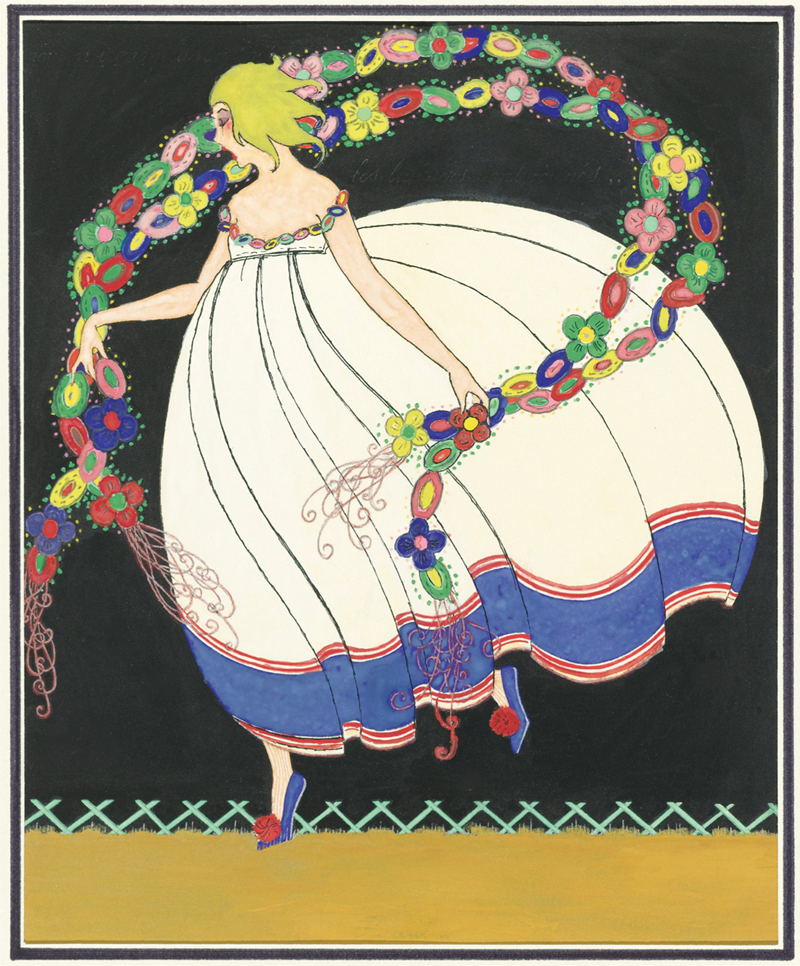

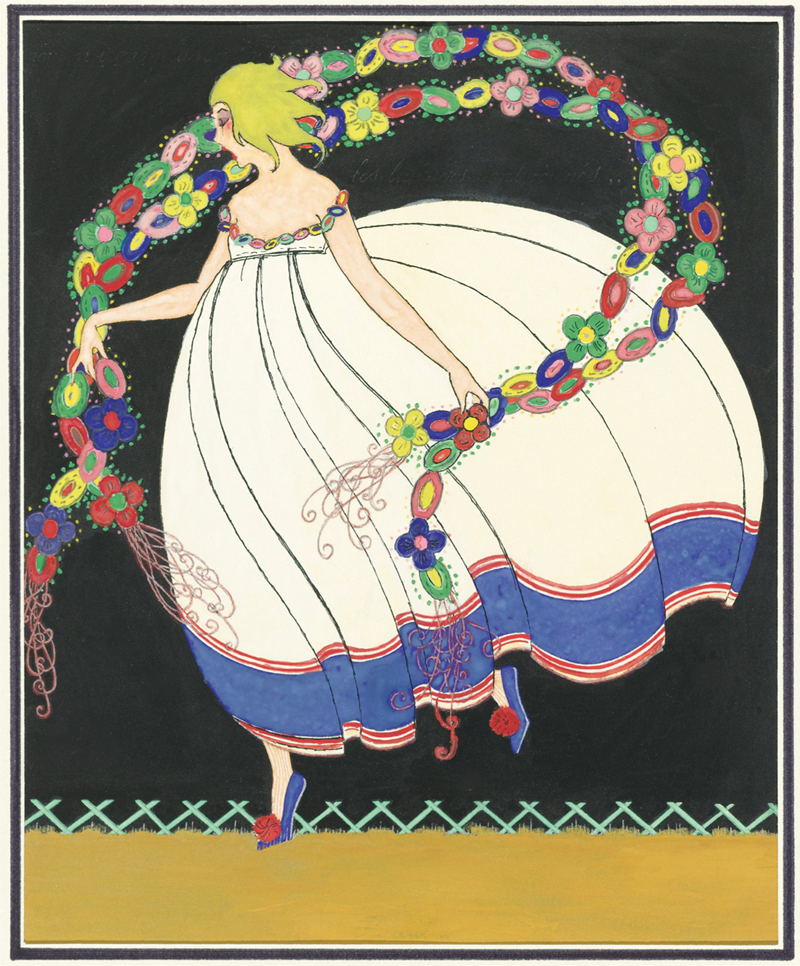

Woman with a garland of flowers, c. 191020.

One reason we love flowers is because they help us talk to each other about the big and small questions of life: about love, death, class, fashion, the weather, art, disease, an allegiance to a nation, religion or political cause, the challenges of space and the passage of time. Flowers are one of the most ancient of mediums through which we communicate. We send them, or their representations, to announce romantic intentions, convey condolences or proffer apologies. Flowers play a part in public health campaigns and in the remembrance of, and opposition to, war. Laura Dowling recently wrote a memoir of conducting floral diplomacy for the Obama administration. Beyond the White House, the carnation has spoken of revolution in Russia and Portugal, while saffron now tells the tale of Hindu nationalism in India. Protestants and Catholics in Ireland each have their own lily. In China, the sunflower generation is still coming to terms with Maos legacy. All of these stories feature here.

A book about people and plants is also a book about greetings cards, badges, proverbs, lamps, songs, photographs, medicine, movies, politics, religion and food. Its about painting and plays, poetry and novels for these are places where the myriad meanings of flowers are explored, challenged and reworked. And the metaphorical traffic is two-way. Almost since books were invented, they have been compared to walled gardens, garlands and bouquets, especially when they bring together disparate material. The word anthology, which originally meant a gathering (legein) of flowers (anthos), highlighted the fact that what was offered was a particular, even an artful, selection.

Blooming Flowers follows in this tradition, gathering together sixteen very different plants garden and florists favourites alongside agricultural crops. There are annuals and perennials, shrubs and trees. I have not tried to represent a different genus with each plant, in fact a quarter of the book explores members of the large Asteraceae (daisy) family, or even to highlight flowers of different colours theres a lot of yellow in here! But variety enters in different ways. Some are wild flowers with ancient associations; other plants rose to prominence with the spread of empire, or are the products of recent industrial floriculture. The result is what the florists call a mixed bunch. My sixteen would struggle to inhabit the same vase the saffron crocus is only inches high and almond blossom grows on trees but in a book (and this is one of the great advantages of books), they can sit side by side. And while I cant promise that my prose will be as colourful and fragrant (as flowery) as the average bouquet, I hope it will last a little longer.

Next page