Wisteria sinensis , wisteria; see .

We all know about bees (and butterflies), and many of us live in countries where it is easily understood that some birds undertake pollination too. The first flowers, however, were probably pollinated by beetles, and since then many plants have evolved to aim their lures at flies, wasps, slugs, mice, bats, lizards and monkeys. It might even be argued that some plants in cultivation have evolved to be pollinated by us, in the form of breeders waving fine-point scissors and narrow brushes to transmit pollen carefully from one specifically chosen flower to another.

Flowers once cut are abstracted from the plant that grows them, to be put in a vase, strung on a thread to decorate a sacred image, or added to food; separated from the plant that bears them, they are inevitably temporary, transient, fleeting. However, cultures that learned to grow crops soon turned their hand to growing flowers, too; garden flowers will repeat (grow again) often for many years, or at least scatter their seed to ensure flowering the next year, making them a much more lasting proposition.

Prunus x yedoensis Somei-Yoshino, Japanese cherry; see .

The beauty of flowers is to some extent compromised by their transience we cannot enjoy them for long. Since the vast majority appear at a particular time of year, that transience is linked to an appreciation and celebration of the seasons. Many have, not surprisingly, become seasonal icons and symbols: among them tulips for spring, chrysanthemums for autumn and cyclamen for winter. Flowers themselves may come and go quickly, but in some species the specially evolved leaves around them last much longer, giving them a quality of longevity that has particularly recommended them to us. With bougainvilleas, arum lilies and poinsettias, for example, most of us are hardly aware of the flowers, only the large, colourful and durable bracts.

Flowers may have co-evolved with their pollinators, but humanity has introduced a very different set of criteria in the process of breeding. Double flowers dysfunctional freaks of nature, but selected and propagated by gardeners have often been a favourite, for millennia in the case of the rose. Nature often throws up other mutations, such as white flowers, or colours that are distinct and different from the normal run of the species. These colour breaks are one of the drivers of breeding for the cut-flower and nursery industry; we humans, it seems, want to have our flowers in all colours, hence blue roses and pink daffodils. Plants with flowers that are genetically malleable, that make themselves available in different shapes and colours, have proved particularly popular throughout history.

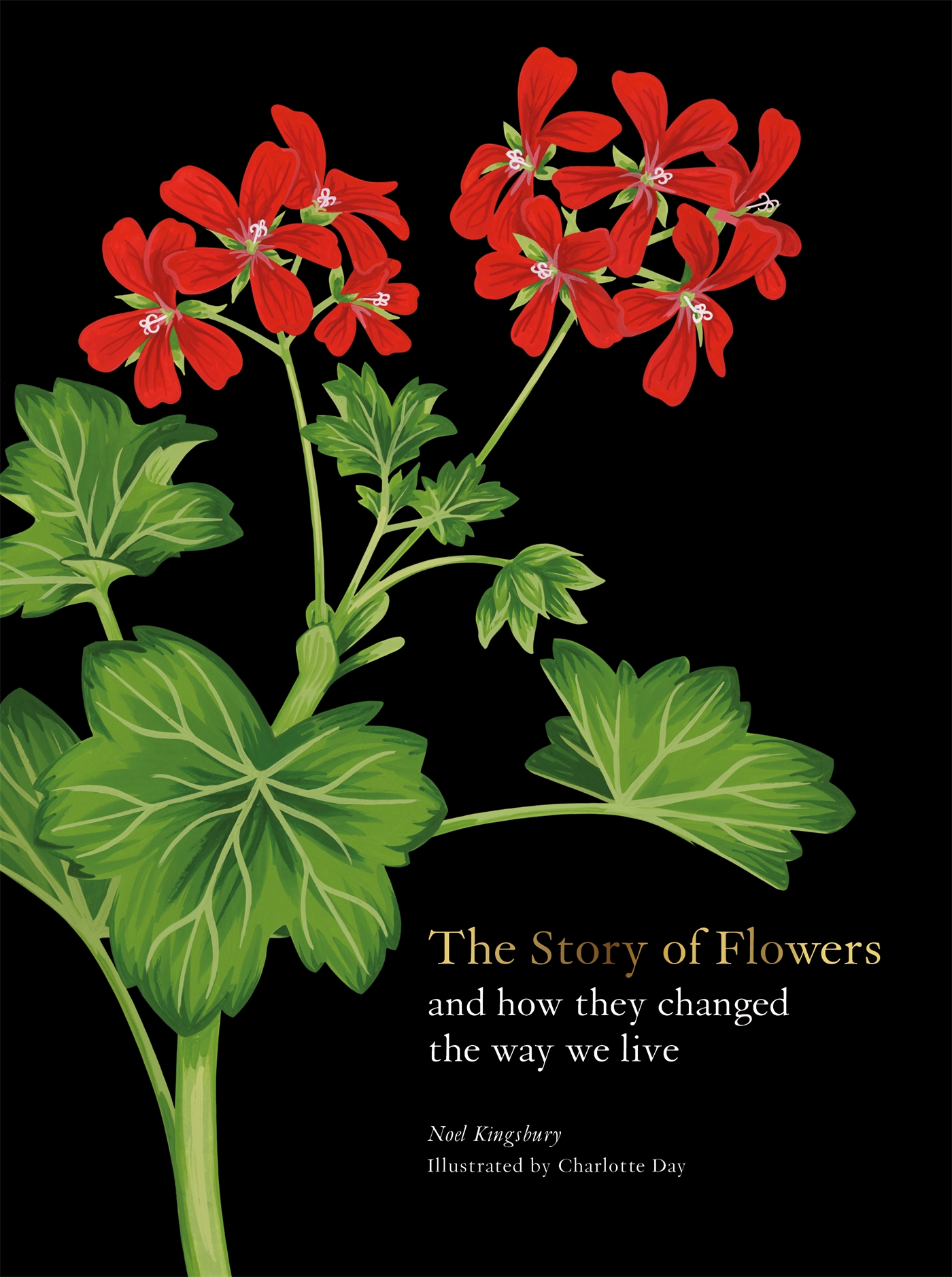

Our one hundred flowers appear here in a very approximate historical order, arranged alphabetically by Latin name within each period. We start with the classical world of ancient Greece and Rome, from which we have a considerable body of literature, many mentions of particular flowering plants, and even images of some preserved in Roman frescoes. We move on to the post-Roman world, including, crucially, Tang-dynasty China, one of the worlds great civilizational moments. Many of the favourite flowers of this period had been in cultivation for a long time before it, but records are sketchy; in the Tang, however, we see the creation of one of the worlds most influential garden traditions.

Our story then moves to the medieval period in Europe, a much maligned era when in fact real progress was made on many fronts, in gardening as much as anything else. This was also the era when the Islamic world developed a rich garden culture, which was increasingly shared with Europe. The centuries between the medieval era and the rapid changes of the nineteenth century were dominated horticulturally by the Edo period in Japan, an extraordinary time when the country turned inwards and gardening became an obsession for a relatively prosperous population. In the nineteenth century the Age of Empire an enormous range of plants were introduced to Europe and North America from all over the world, and gardening came of age as a mass-market hobby in the newly industrialized countries. We end in the twentieth century, when growing sophistication and consumer demand greatly increased the quantity and range of species grown.

Viola odorata , sweet violet; see .

It remains to be seen what new developments will transpire as the twenty-first century progresses. Perhaps varieties that are little thought of now will come to new prominence, not to mention the breakthroughs that will inevitably result from new developments in plant-breeding and genetic engineering. There is certainly always the appetite for flowers, both commercially and as something very close to most human hearts.