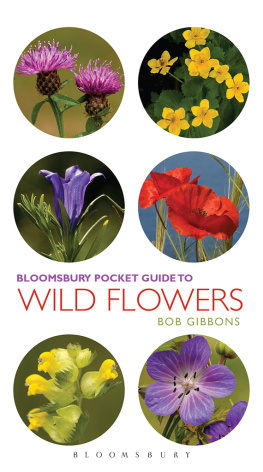

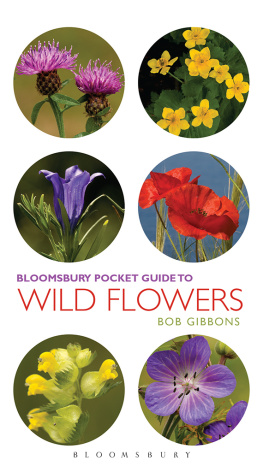

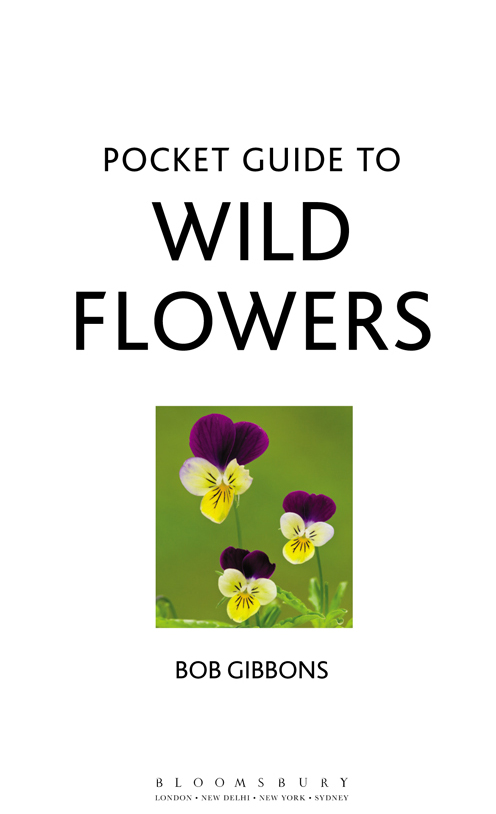

This book is intended as a handy guide that can readily be taken out into the countryside and used to identify some of the most attractive, abundant and conspicuous flowers of Britain and adjacent parts of Europe. It does not, of course, cover all the flowers of this area, and the selected species are ones that you are generally most likely to see. Where appropriate, a selection of similar species is included with the main species.

The order of species within the book follows the most widely used taxonomic system. At present, botanical naming is in a state of considerable flux because of the vast amounts of new information arising from DNA analysis of plants. The process is by no means complete but has already led to much reclassifying and renaming of species. This book follows the nomenclature of the New Flora of the British Isles, third edition, by C. Stace (see ); older names are also given where they are still widely used.

The species are described in a standardised way, comprising a simple description of the plant, its flowering time, usual habitat preferences and broad distribution within the British Isles including Eire. What is included in the description varies the salient points that distinguish each species are covered. For example, in the mulleins there is a description of the colour of the hairs on the filaments of the stamens because this feature is important for identifying mulleins, but this characteristic is not described elsewhere. The flowering time indicated is the main period of flowering, but plants are likely to flower latest further north and at high altitudes, and flowering periods vary from year to year. In addition, small numbers of flowers may be found well outside the normal period of flowering, so the dates given should be treated as a guide only. The habitat preferences given are the most frequent ones and may not cover all the situations in which a plant occurs, and plants may grow in different habitats in different countries.

Following the description of the main species on the page, a number of similar or closely related species may be described. The descriptions are short, simply outlining the key differences from the main species.

The book is intended primarily as an accessible visual guide, with the photographs giving the primary clue to each flowers identity, to be confirmed by study of the more detailed descriptions and similar species where applicable.

Foxglove flowers Digitalis purpurea

THE STRUCTURE OF FLOWERS

Flowers vary hugely in their form and colour, depending on how they are pollinated, where they grow and how they have evolved. It is not possible here to describe and explain the whole range of flower structures, but there are some simple, general rules that can be followed.

Flowers consist of several whorls of parts that may or may not be symmetrically arranged. The outermost whorl (which is often, but not necessarily, green) is known as the calyx. This is made up of individual sepals that may be separate or fused into a tube with just the tips free, indicating the number of sepals making up the tube. The primary function of the calyx is to protect the bud, though in many species the sepals are adapted to be part of the pollination mechanism. In some species the calyx may be missing or adapted to be similar to the petals for example in anemones, where there is no obvious calyx, and in many orchids, where the sepals are petal-like and are significant parts of the insect-attracting mechanism. In a few plant groups, notably the rose and mallow families, there is an additional epicalyx outside the calyx, but this is the exception rather than the rule. Its presence can be helpful in identifying these families.

The next whorl in towards the centre of a flower is composed of the petals, which are most commonly what we think of as the flower. They are frequently highly coloured and conspicuous, and form the key feature in attracting insects to pollinate. The form of petals, and their arrangement, varies enormously. One common form is a simple ring of roughly equal petals as, for example, in cranesbills and buttercups; in other species, such as the bellflowers, the petals are fused into a tube. In many groups, the petals have evolved individually and are no longer all similar in shape in the pea family, one petal forms the large raised standard and two form projecting wings, enclosing two more fused into a keel. An extreme variation occurs in the orchids, especially in the genus Ophrys, such as the . Here the three sepals are usually strongly coloured and resemble petals; the lowest petal, known as the labellum or lip, has developed into a form resembling the body of a bumblebee, while the remaining two petals are small, looking something like the antennae of an insect. The whole is part of a complex process of duping male bees and wasps into thinking that the plant is a female insect ready for mating a process known as pseudocopulation.

Within the ring of petals lie the reproductive parts of the flower. The male parts are the stamens, usually each consisting of an anther, where the pollen is produced, and a filament that is, its stalk. The male genes are carried in the pollen by wind, insects or other means. The female parts are more variable, made up of one to many carpels, each containing one or more ovaries. A carpel normally has a stalk-like style that terminates in a receptive stigma, where the pollen settles and germinates. The number and arrangement of these parts is an important component of plant identification.

The leaves of plants are also important in their identification, particularly their shape, whether they are toothed or not and whether stalked or not, and whether they are arranged in opposite pairs, alternately up the stem, or in some other way. The presence, absence and shape of two little leaf-like structures at the base of the leaf stalk known as stipules are also important.

Wild plants are under threat everywhere, and many have declined alarmingly. Please pick them only if necessary, never dig them up and join as many wildlife conservation organizations as you can.

The distinctive flowers of Bluebell Hyacinthoides non-scripta

WHITE WATERLILY

Nymphaea alba

One of northern Europes most distinctive and attractive wild plants, White Waterlily is an aquatic perennial with large, leathery, almost circular floating leaves that have veins radiating from the centre, where the stalk joins the blade. The flowers are very large, up to 20cm across, scented, with numerous white petals, some of which are longer than the four green sepals. They open fully only in bright conditions. The fruits are ovoid to spherical and fleshy, though rarely seen because they ripen below the waters surface. When mature, the fruits sink to the bottom and decay to release the seeds.