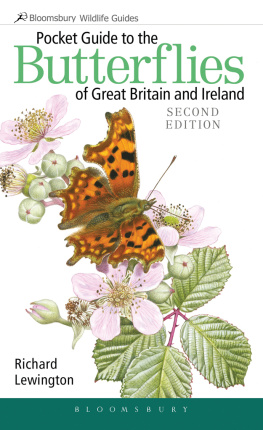

This electronic edition published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

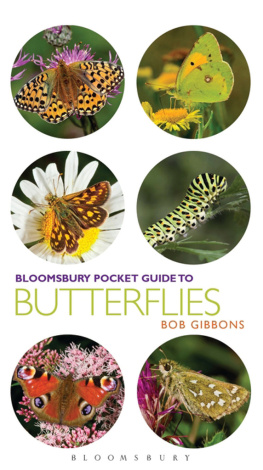

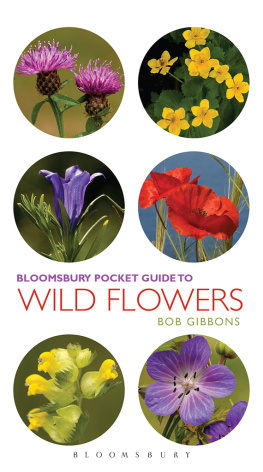

First published in 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc,

50 Bedford Square, London WC1B 3DP

www.bloomsbury.com

Bloomsbury is a trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing plc

Copyright 2015 text by Bob Gibbons

Copyright @ 2015 photographs by Bob Gibbons and Richard Revels

The right of Bob Gibbons to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN (print) 978-1-4729-1592-4

ISBN (ePub) 978-1-4729-1594-8

ISBN (ePDF) 978-1-4729-1593-1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for

Publisher: Nigel Redman

Project editor: Jane Lawes

Design by Rod Teasdale

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

WHAT IS A BUTTERFLY?

Butterflies are part of a large order of insects, the Lepidoptera, which also includes the moths. The characteristics of the whole order are wings covered in scales (lepidoptera means scale wings), which give them their colour and pattern, and, normally, a long sucking proboscis that is coiled up under the head when not in use. This is used for drinking nectar and other fluids, the primary source of food for the adults.

Moths and butterflies differ in a number of ways. Within northern Europe all butterflies are day flying only, whereas most moths are night flying, although there are a number of day-flying moths that do resemble butterflies. All our butterflies have distinctly clubbed antennae, and there is a sharply defined, short swelling at the tip of each antenna. Most moths do not have this feature, but some, such as the day-flying burnet moths, have antennae that taper gradually from a swollen tip. Most moths rest with their wings folded back along their bodies, whereas most butterflies fold their wings above the body, revealing only the undersides. Finally, on detailed examination moths can be seen to have their forewings and hindwings attached together by little hooks, each called a frenulum, whereas butterfly wings simply have a large area of overlap. This combination of characteristics, and particularly the antennae, serves to distinguish the two groups.

Superficially, butterflies can also be confused with the owl-flies, or ascalaphids, which are active, day-flying insects in warm, grassy sites throughout southern and central Europe (but not the UK). They differ from butterflies in having very long, clubbed antennae and large, clear patches on the wings, and by their active predatory lifestyles.

THE LIFE OF A BUTTERFLY

All butterflies pass through a series of stages in their lives, known as complete metamorphosis. The females of adult butterflies lay eggs on specific food plants or groups of food plants, which they select; occasionally the eggs are deliberately laid away from the food plant, but near it. The eggs hatch to produce larvae, or caterpillars, which feed on the food plant, passing through a number of stages until they are fully grown. The larva is the main feeding and growing phase of the life cycle. When it reaches a certain size, a larva ceases feeding and turns into a pupa, or chrysalis, in a process known as pupation. This is an immobile phase and pupae are hidden somewhere attached to the food plant, in soil or in some other suitable place. Within the pupa an extraordinary process takes place, during which the body is effectively gradually reassembled into the form of an adult butterfly. When ready, the fully formed adult breaks out of the pupa. At first it is relatively small and shrivelled looking, unable to fly and vulnerable to predation. Within a few hours, however, the wings are inflated to their full size, and the butterfly is able to fly as a sexually mature adult.

The main function of the adult part of the life cycle is breeding and dispersal. Adults feed regularly on nectar and other nutritious liquids, primarily to gain energy, not growth. When not feeding, basking or sheltering from inclement weather, the males spend most of their time defending territories, seeing off potential rivals and seeking out females with which to mate. Females behave rather differently, spending much of their time searching for suitable plants on which to lay their eggs. Males are frequently more conspicuous than females for this reason, although not in all species.

Butterflies vary widely in their mobility and powers of dispersal. Some, such as the , are highly mobile, moving widely in search of mates, nectar or larval food plants, although they are not migratory in the sense of having regular defined movements over long distances.

A number of species are regular migrants, most commonly migrating northwards from a southern base (typically in the Mediterranean area) whenever populations build up. The pattern of these migrations varies widely. Some species perform reverse migrations (much has been discovered about this in recent years see , for example), while others do not return south. In some cases the migrants reinforce existing resident populations, while others only occur as migrants. In more extreme cases American species, notably the Monarch Danaus plexippus, appear in north-west Europe when they are blown off course from their regular extraordinary northsouth migrations within the American continent. Nowadays there are examples of human-assisted migration; for instance, the Geranium Bronze Cacyreus marshalli, from South Africa, has become established as a resident in parts of southern Europe due to its introduction there with pot plants, and the availability of suitable garden plants as larval food. It is recorded occasionally in Britain, but has not become established.

FINDING AND WATCHING BUTTERFLIES

Although butterflies occur almost everywhere, it can be surprisingly difficult to find specific species without local knowledge. In general, the best way to discover a range of interesting and attractive butterflies is by visiting high-quality, semi-natural habitats such as chalk grassland (especially in June and July), old woodland (especially spring and summer), heathland (especially summer) and gardens at almost any time. All of these are rich in insect life unless they are badly polluted.

Nature reserves frequently preserve the best examples of these habitats, and most are open to the public. Some examples of organisations that have reserves are given . It is also worth searching the internet as there are many websites that give details of good sites for particular species.

When out in the field it is best to walk slowly and scan ahead, to try and see the butterflies before they see you. If you approach slowly they will often not see you as a threat and may stay put. It is always a good idea to carry binoculars, particularly for viewing tree-based species such as some hairstreaks and . Consider close-focusing binoculars (such as the Pentax Papilio, which is small, light and extremely close focusing, specifically for butterfly watching); these will allow you to examine the features of butterflies in detail.

Next page