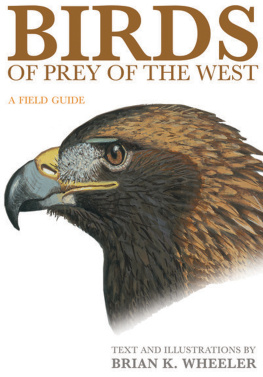

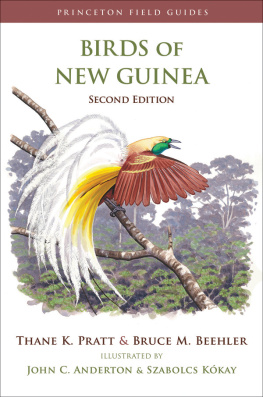

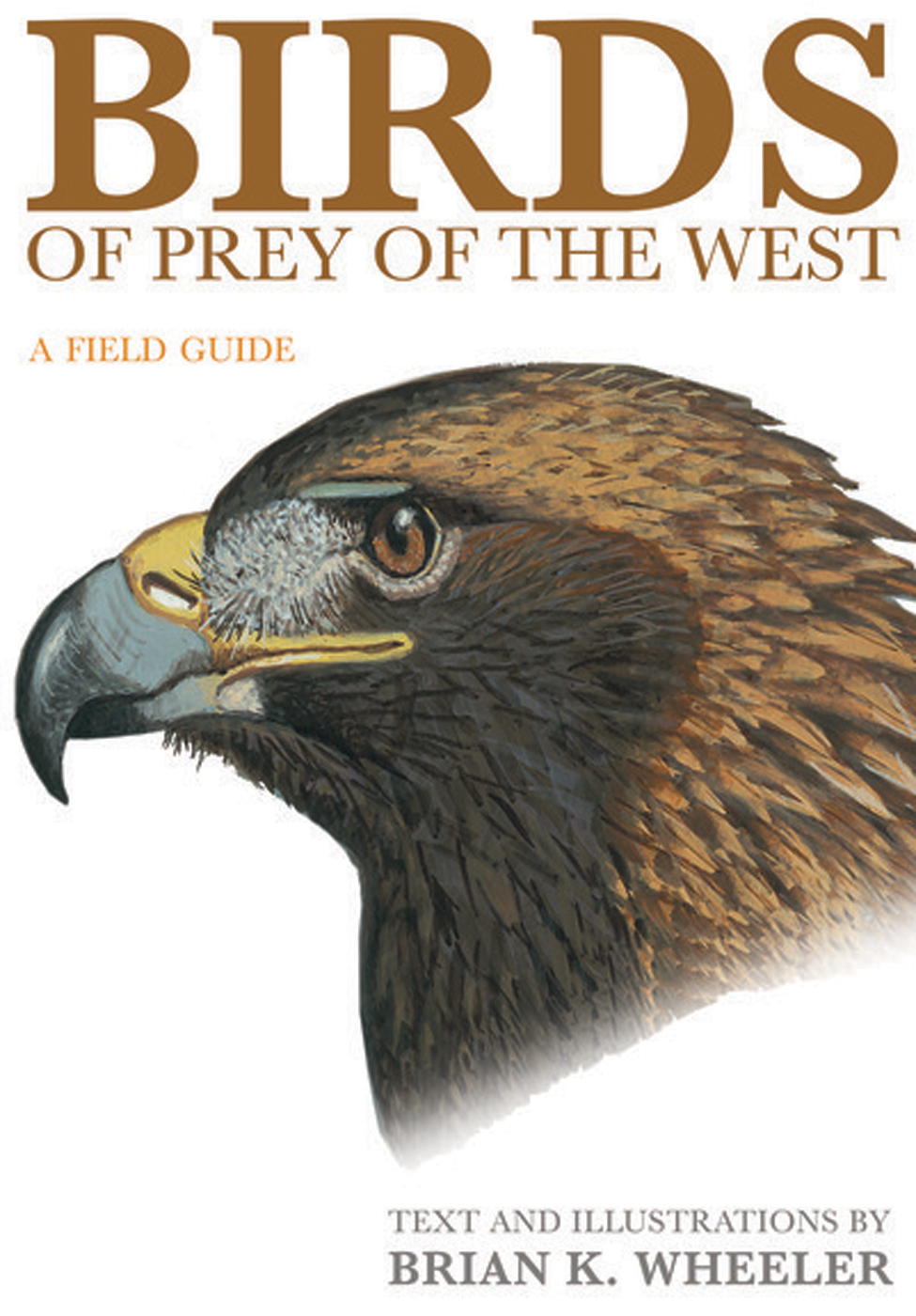

Birds of Prey of the West

A Field Guide

Illustrations and Text

by Brian K. Wheeler

Range maps researched by

John Economidy and Brian K. Wheeler

and produced by John Economidy

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2018 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press,

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press,

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

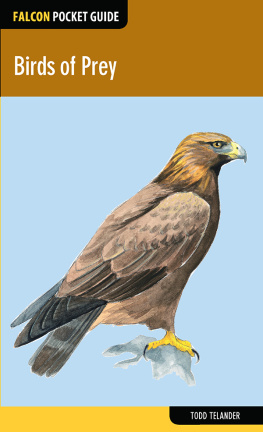

COVER ARTWORK

Golden Eagle: A regal member of the order Accipitriformes, which, since 2012, includes all diurnal raptors, except falcons and vultures. This impressive bird of prey is uncommon but widespread west of the Great Plains and throughout w. Canada and Alaska. It is found east of the Great Plains during winter. Golden Eagles suffer from ingestion of lead bullet fragments when scavenging, leg hold traps, shooting, and wind turbines.

All photographs were taken by the author unless individually credited

All Rights Reserved

ISBN (pbk.) 978-0-691-11718-8

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017949016

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

This book has been composed in Minion Pro and Myriad Pro

Printed on acid-free paper.

Printed in China

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To my wife, Lisa,

and my son, Garrett,

with all my love

A special thank you to

Ned and Linda Harris

In memory of Joe Harrison and

Wayne Johnston

Contents

List of Plates

Grand Canyon National Park (South Rim), Coconino Co., Ariz. (Jun. 2008)

California Condor, adult (#33). As with all Condors, this 12-year-old bird must survive the perils of lead poisoning.

Preface

This book is a culmination of data and knowledge from over 50 years of painting birds and studying raptors.

The journey began when I was seven years old, when I earnestly started drawing birds and mammals, first on old canvas pieces, then on cardboard, and then on white watercolor paper with transparent watercolor paint. Later, I used the thicker opaque watercolor medium called gouache. This paint allowed me to paint on surfaces other than white paper. Gouache also allows more detail than transparent watercolor. Since the 1980s, all paintings have been done on variously colored 100 percent rag, acid-free mat boards, which brought more atmosphere to my developing style of painting.

An innate desire to replicate realism motivated me even at that early age. My first watercolor paintings of wildlife date back to age 12, and I sold my first painting when I was 14. Painting wildlife and especially birds was my passion, and I drew or painted every day. By my early 20s, I concentrated mainly on birds and only rarely painted mammals (a life-size Red Fox in the snow was one of my favorites among the last mammals I paintedand the largest mammal I painted life-size).

My late teens and 20s were spent learning bird anatomy. I spent much time with waterfowl hunters and preparing road- and window-killed specimens for museums, first for Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant, Mich., and later for Yale Universitys Peabody Museum, New Haven, Conn. I have always constructed my bird figures based on my anatomy studies rather than by copying photographs, though I have always used photos as references, especially for accurate color of fleshy areas and proportionsespecially later for flight images. The only photography I did at the time was of close-ups of the heads and feet of freshly collected waterfowl to capture fresh coloration. Most of my time was spent doing a massive amount of field sketching of birds using a spotting scope.

I was naturally inspired by the impressive life-size works of John James Audubon. Even though his figures were anatomically distorted and stylized, he was a highly skilled technician. The exquisite paintings of Louis Agassiz Furetes (in Birds of America, Doubleday & Co., 1936 [especially ]) inspired me for many years. J. F. Landsdowne, the awesome bird painter from British Columbia, Canada, impressed me the most, with his super-realistic, close-focus vignette bird illustrations. Though much different from what I do, the full-background, mood-laden shorebird paintings by Robert Verity Clem are incredible.

At 20, I moved from Michigan to Connecticut to attend the Paier School of Art (now Paier College of Art). I selected this school because it had a strong culture of realism and superbly talented instructors. I was self-taught in my preferred medium of gouache, which I started using crudely in my early painting career. When I got to art school, I was toldin so many wordsI was not using gouache in the proper method. Other paint mediums and aspects of art were of course explored, but gouache suited my style, and I perfected my improper painting method even more. After two and a half years of formal trainingand out of funds to attend the balance of the four yearsI embarked on a freelance career as a gallery-type life-size-bird painter.

Virtually all of my bird paintingexcept in my early yearsconsisted of life-size renditions, mainly in vignette style, that captured the intimate character of the bird with limited, close-focus, detailed background. (I love painting wood grain in branches and logs.) The use of the colored mat boards gave more breadth and character to my limited-background works.

I did full background paintings on occasion, also in close-focus format: a life-size Barn Owl perched in a barn window, with broken glass pieces on the edge of the window pane and red paint peeling off the wood, is my all-time favorite.

My paintings were sold through galleries to private and corporate clients (mainly in Michigan, Connecticut, and New York City). I succeeded in making a living creating life-size bird paintings for 12 years (197890). The recession of the late 1980s set in, which closed galleries and, by 1991, forced me to find other means to put food on the table and pay bills.

Most of my life-size works were of commercially appealing, decorative types of birds, particularly waterfowl, upland game birds, and of course pretty songbirds (I painted lots and lots of Northern Cardinals). All paintings, including book illustrations, were done with a museum specimen in my left handor on a nearby table if a large birdand a paintbrush in my right hand. (I was always fortunate to have ready access to major natural history museums, and I would check bird specimens out like library books; specimens were safely housed and transported in a metal container.)

One of my greatest accomplishmentsand far different from any other workswas a commissioned four-by-five-foot mural to commemorate the extinct Passenger Pigeon. This impressive painting is on permanent display at the Chippewa Nature Center, Midland, Mich. The painting was done in oil on Masonite board and depicts a full-background market-hunting scene from the mid-1800s. It has life-size pigeons in the foreground and market hunters with wagons in the middle ground. It is also the only painting I have done since my art-school days that had human figures in it. (A friend modeled various poses for me with a shotgun; figures are about 10 inches tall.)

Birds of prey have been my thing since my childhood days, even though I did not regularly paint raptors for gallery sales, becauseexcept for falcons and owlsmost do not possess the commercial qualities of songbirds and game birds. I did, however, spend much of my time studying diurnal raptors: finding nests, banding birds, and watching and photographing them across the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

Next page