To Alexandra Georgia Lewington

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Martin Harvey for his help in the preparation of this book, Richard Fox of Butterfly Conservation, and my editors, Anne and Andrew Branson and Katy Roper for their enthusiasm and guidance. The maps are based on information kindly supplied by Butterfly Conservation and the Biological Records Centre.

Second edition first published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Kemp House

Chawley Park

Cumnor Hill

Oxford

OX2 9PH

First edition published 2003

Reprinted 2004, 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2013

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

copyright text and illustrations Richard Lewington 2003, 2015

Richard Lewington has asserted his right under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the Author of this work.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN 978-1-910389-04-1 (PB)

ISBN: 978-1-472938-79-4 (eBook)

To find out more about our authors and their books please visit www.bloomsbury.com where you will find extracts, author interviews and details of forthcoming events, and to be the first to hear about latest releases and special offers, sign up for our newsletters.

Introduction

B utterfly-watching is now a popular and enjoyable pastime for many people. As a result, new discoveries are still being made to add to the already considerable knowledge of Britains butterflies. From the 18th century, through the days of the Victorian collectors when butterfly-collecting was at its peak, to the present day, much information on these insects has been recorded, and no other countrys butterflies have been so thoroughly studied.

These days, photography has largely replaced the need to collect specimens, and many people who are keen on wildlife and photography spend much of their time building up collections of butterfly photographs. New information, even about common species, is still being acquired and even the novice can add to the overall picture by observing and recording butterflies. Sightings can be sent to organisations, such as Butterfly Conservation, which collate records. From this information and our observations, fluctuation in populations can be determined.

Before records can be made, however, it is necessary for the observer to be familiar with our butterflies so that a positive identification is achieved. Sadly, Britain and Ireland have very few butterflies compared with the rest of Europe just 57 residents compared with more than 500 species on the Continent but even so we have some species that are tricky to tell apart. The main aim of this book is to provide the clearest possible means of identification, with illustrations of the upper and undersides of every resident and migrant British species, together with their early stages. As well as all the British butterflies, a few well-known and common day-flying moths have been included, as these are often encountered in the countryside by butterfly recorders.

Opinions differ as to the relative merits of photographs and paintings for identifying butterflies. The variability of photography can lead to confusion, but the use of accurate artwork can pinpoint fine details and differences between similar species and so result in more accurate identification.

Conservation

T he decline of Britains butterflies throughout the last century, and particularly since the Second World War, has been dramatic and a cause for great concern, not only to naturalists but also to many people who can still remember the pleasure of seeing wildflower meadows dancing with butterflies. The all-too-familiar story of habitat destruction, agricultural intensification, pollution and the ever-increasing demands on land, has resulted in all forms of wildlife, not just butterflies, suffering.

The possible effects of climate change may also influence the future of our butterflies. While slightly higher temperatures may benefit some species, the unpredictability of weather patterns could have a detrimental effect on others, and the outlook for some of our northern species, such as the Mountain Ringlet, is uncertain. Some rare species with specific habitat requirements, such as the Swallowtail, have benefited once conservation organisations have discovered their exact needs and put into effect appropriate management. However, it is worrying that some of the commoner species, such as Wall and Small Copper, have declined for reasons that are unclear. It is, therefore, vital that a greater understanding of our butterflies is reached and the monitoring of their populations continues, so this information can be integrated into management strategies for their habitats.

Butterfly Conservation is the largest insect conservation charity in Europe, with 25,000 members and many volunteer branches throughout the UK. Its aim is the conservation of butterflies, moths and their habitats. Through its volunteers and staff, the Society runs conservation programmes, organises national butterfly and moth recording and monitoring schemes and manages 35 nature reserves covering 785 hectares. The Society welcomes all newcomers to butterfly-watching and conservation who wish to participate in any of its activities.

Further information on how you can become involved and make a real contribution to helping and enjoying butterflies can be obtained from: Butterfly Conservation, Manor Yard, East Lulworth, Wareham, Dorset BH20 5QP; tel: 01929 400209.

e-mail:

website: www.butterfly-conservation.org

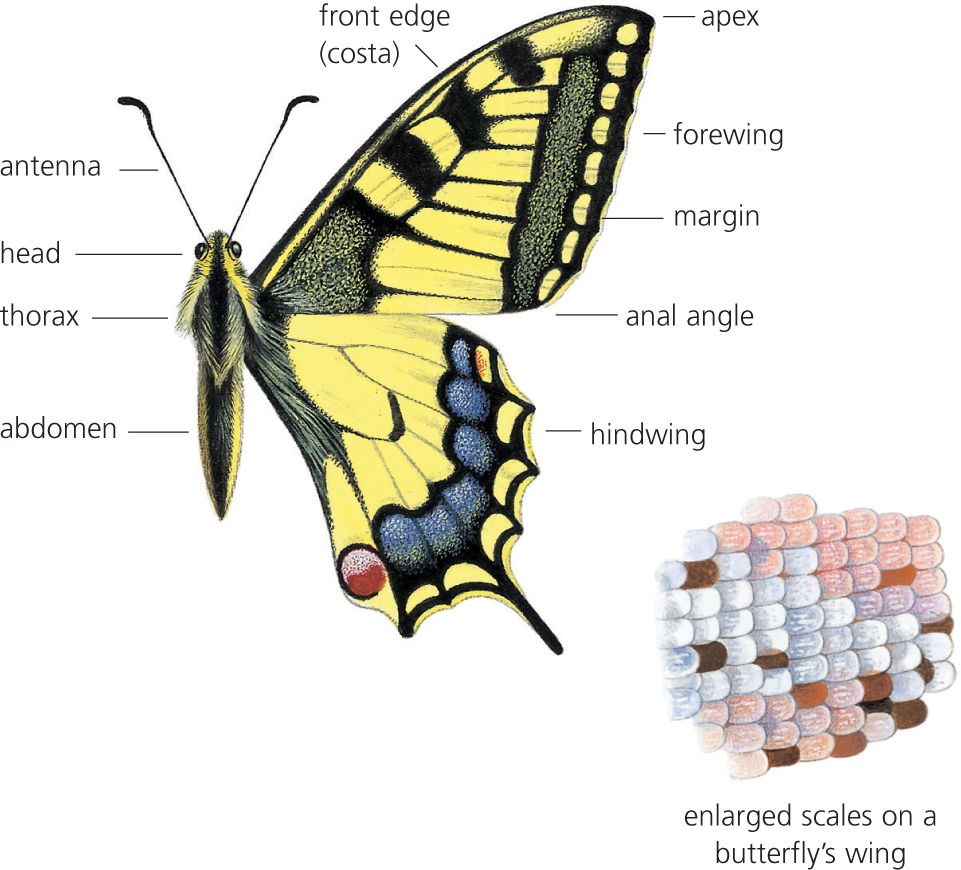

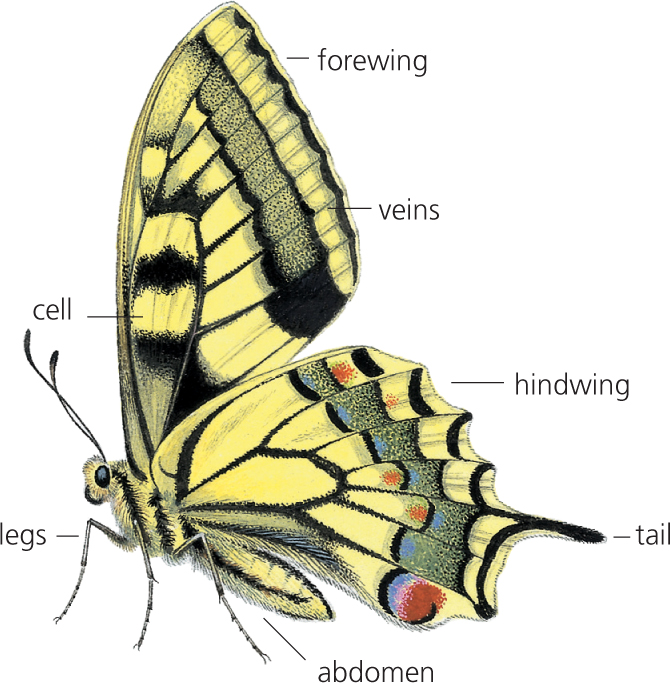

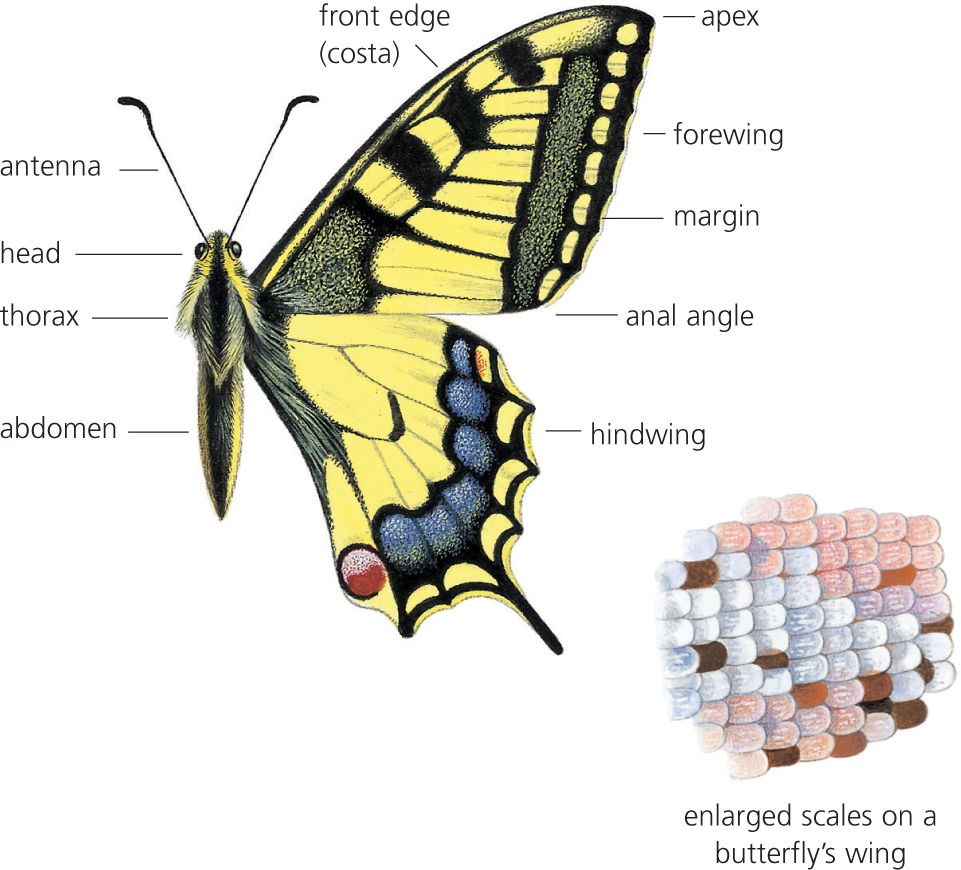

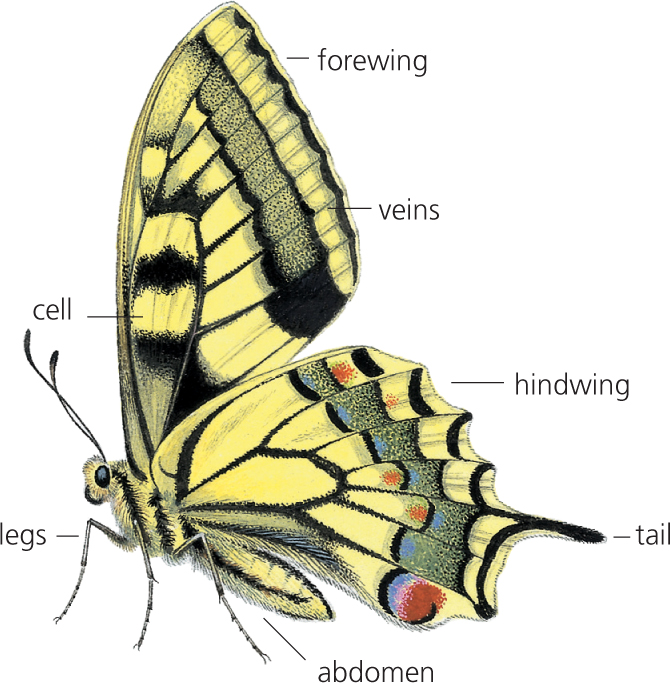

The structure of a butterfly

B utterflies belong to the order of insects known as Lepidoptera, meaning scale wing, and it is the overlapping formation of these pigmented and reflective scales that gives butterflies and moths their wonderful variety of colours which make them unique. The two pairs of membranous wings are attached to the thorax and are supported by a network of veins, which are inflated and hardened when the butterfly emerges from its chrysalis. The main parts of a butterflys wings and body referred to in the species accounts are detailed below.

Upperside

Underside

The life cycle of a butterfly

A butterfly has four stages in its life cycle. It starts as an egg, which may hatch after a few days or pass the entire winter with the tiny caterpillar formed inside. The caterpillar is the eating and growing stage, and can last from three weeks to more than 20 months in species which hibernate twice; this is the most familiar stage, after the adult. The chrysalis is the stage in which the greatest internal transition takes place, and often in just a few weeks a yellow liquid broth turns into a fully formed butterfly, which breaks out and expands its wings in preparation for a life which may last from just four days to 11 months.