All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Clarkson Potter/Publishers, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York

CLARKSON POTTER is a trademark and POTTER with colophon is a registered trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Foreword

A gaggle of teenage girls screaming ecstatically for the latest boy band may not seem to share much with their Victorian counterparts giggling over a floral dictionary. But like a focus on boy bands or fan fiction, the language of flowersembedding secret messages in bouquets, according to meanings listed in special floral dictionariesprovided young women throughout the nineteenth century with a vital emotional outlet. Publishers raced to keep pace. Paging through a beautifully illustrated book, dreaming up possible floral arrangements, alone or with friends, was a fun, socially sanctioned way for girls to explore their evolving identities and the wild churn of their adolescent feelings and fantasies.

The language of flowers was so popular across North America and Europe that it made its way into the lives and works of more than a few legendary authors. As a teen, Mary Ann Evans and her girlfriends consulted a floral dictionary to give one another code names. Thereafter, she signed her letters to them using her playful nom de bloom , if you will: Clematis (mental beauty). Decades later, concerned that readers wouldnt take seriously a novel written by a woman, Mary assumed the pen name George Eliot to publish Middlemarch . Its hard not to wonder if her girlhood game helped inspire that decision, at least subconsciously.

Speaking of the subconscious: A teenage Sigmund Freud and a friend created their own floral language to talk about girls (known as principles) and sexual longings. Only in summer does the delight of the principles come into bloom. I remember a so-called rose garden, a feast of dahlias, he wrote in an 1875 letter. Twenty-five years later, Freud referred to the language of flowers in his famous The Interpretation of Dreams.

Oscar Wilde wore a green carnation in his buttonhole, which many people interpreted as a badge of his queerness; green was an unnatural color for a flower, just as the love between men was considered to be. (A century later, the hip-hop star Tyler, the Creator proudly declared his bisexuality on his 2017 album Flower Boy. In the song Garden Shed, he raps, the garden / That is where I was hidin.) When James Joyce sat down to write Ulysses , he armed himself with all manner of reference materials, including a floral dictionary. No matter: Denizens of the twentieth century, consumed with their passion for progress, did their best to lock away anything associated with the past and throw away the key.

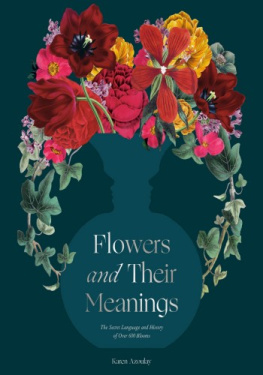

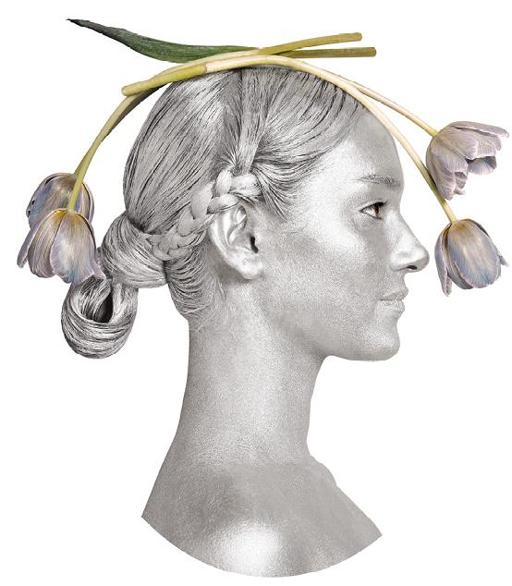

By the time artist Karen Azoulay was born, the language of flowers was nearly extinct. Everybody knew that a red rose means love, but few people knew why, or cared. Fortunately, the metaphorical promises of blossoms and blooms transcend artificial time constraints. Azoulays Canadian girlhood included her Moroccan aunts smearing her hands with paste from the henna plant, believed to transfer good luck. At art school, she explored a growing fascination with historical ideas that involved women, nature, decor, and mythology. In 2005, when she moved to New York City and her first roommate gave her a nineteenth-century floral dictionary of her grandmothers, the gift struck Azoulay as both intriguingly exotic and uncannily familiar.

In this gorgeous and meticulously researched new work, Azoulay shows that humans have celebrated the expressive capabilities of flowers and plants for millennia, all over the world, and will forevermore. Think of the coded language of emoji, she writes. Like a poetic bouquet, a chain of emojis can send a sincere message without uttering a word. It can be hard to express love, lust, and earnest declarations of praise or apology, but a combo of gimmicky symbols feels less vulnerable.

Some of my favorite books are those that take an ordinary element of everyday life and show that its extraordinary. This is one of those books. Before reading it, I rarely thought about flowers. Now I see them everywhere, all the timethe scarlet poppies (fantastic extravagance), deep pink roses (encouragement), and purple morning glories (affection) patterning my favorite dinner napkins; the blue hydrangea (boaster) frilling a neighbors sidewalk garden; my nieces daisy (innocence) earrings. Even better, I understand now that each flower contains a story, and to learn it, all I have to do is open this book.

But this book is so much more than a floral dictionary. It is also one artists testament to her own creative obsessions with the unexpected ways in which nature and humanity overlap. I first met Karen Azoulay in the early aughts when a mutual friend introduced us after another friends fashion show in Manhattans Chelsea neighborhood. I can still see us now, seated on a low, white curvilinear bench. It was summer, the air warm, and her mouth was bright with fuchsia lipstick. We immediately fell to talking, as if we were old friends already, and I felt that wonderful excitement of finding a kindred spirit, someone I could talk to forever. We could have been nine, or nineteen, in our enthusiasm and pleasure for each other. Over the years since, Ive learned that like a magical witch, or a fairy godmother, she is a genius at finding beauty and meaning in what most people ignore, and makes the most ordinary moments feel special and intimate. I cant think of a better twenty-first-century ambassador for the timeless language of flowers.

Kate Bolick

Introduction

Queen victoria (18191901) reigned over the United Kingdom from 1837 until her death in 1901.

It was a crown of orange blossoms that haloed twenty-year-old Queen Victoria on her wedding day. She loved all things floral and was very aware of the hidden meanings they projected. Fluent in the language of flowers, she knew the pale citrus blooms signified chastity, marriage, anddue to the trees generous trait to bear fruit and flowers simultaneouslyfertility. Early in their marriage, Prince Alberts grandmother gifted the young queen some myrtle, a bloom emblematic of love. Victoria had a cutting of the flower planted, and a sprig of myrtle originating from that bush has been included in every British royal wedding bouquet ever since.

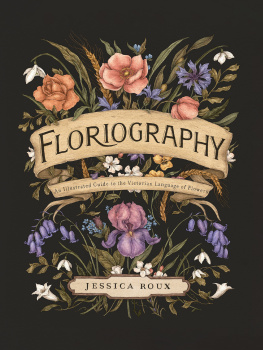

One hundred forty-one years later, when twenty-year-old Diana Spencer walked down the aisle to marry Prince Charles, she held a cascading forty-two-inch-long bouquet. Following tradition, it included some of Victorias love myrtle. The showy floral burst featured many other botanicals, each known for a different sentiment, including ivy (marriage), gardenias (transport of joy), lily of the valley (return of happiness), and veronica (fidelity). Awkwardly tucked in behind all these white flowers, barely visible, were two canary-yellow roses. This variety of Rosa floribunda happened to be named after Lord Mountbatten, Prince Charless deceased mentor and honorary grandfather. Presumably they were placed in his memory, but yellow roses are also known to signify jealousy and infidelity. Is it going too far to suspect the aggrieved Diana was expressing a complaint she could not yet dare speak aloud? This elaborate form of covert communicationbroadcasting and interpreting emotions embedded in floral arrangementsis the art of floriography.