Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Dr. Robert J. Chandler,

historian extraordinaire

In all of recorded history, mankind has needed to transfer money and goods from one place to another. The enduring difficulty has been finding a safe way to do it. From marauding brigands attacking desert caravans, to pirates on the high seas, to robbers of Wells Fargo stagecoaches, and to modern hackers stealing identities on the Internet, security has remained one of our greatest challenges. For the simple truth is this: As soon as someone gets legitimate wealth, there is always a crook figuring out how to steal it. And with every new secure method to transfer money, criminals are quick to catch up.

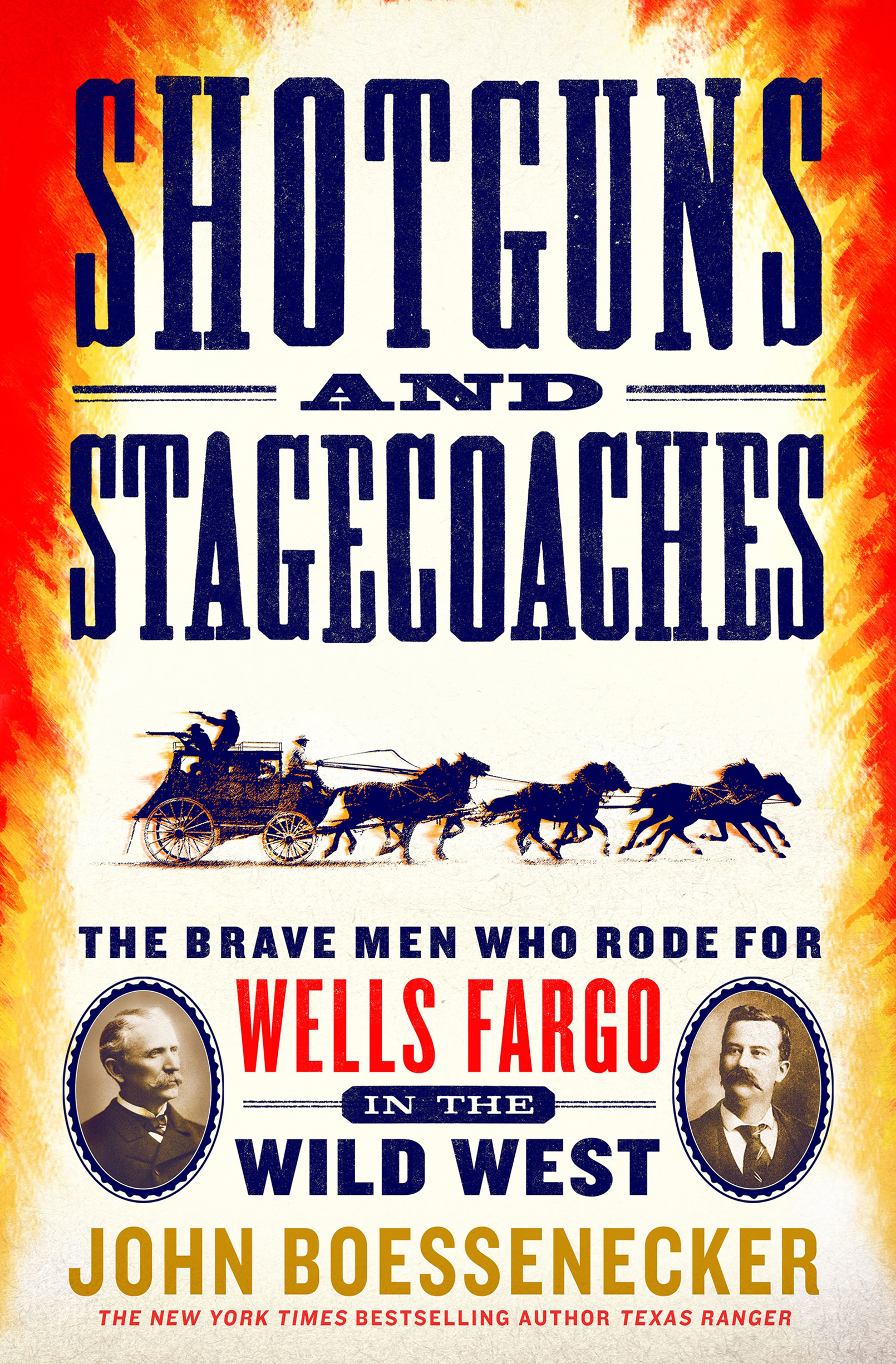

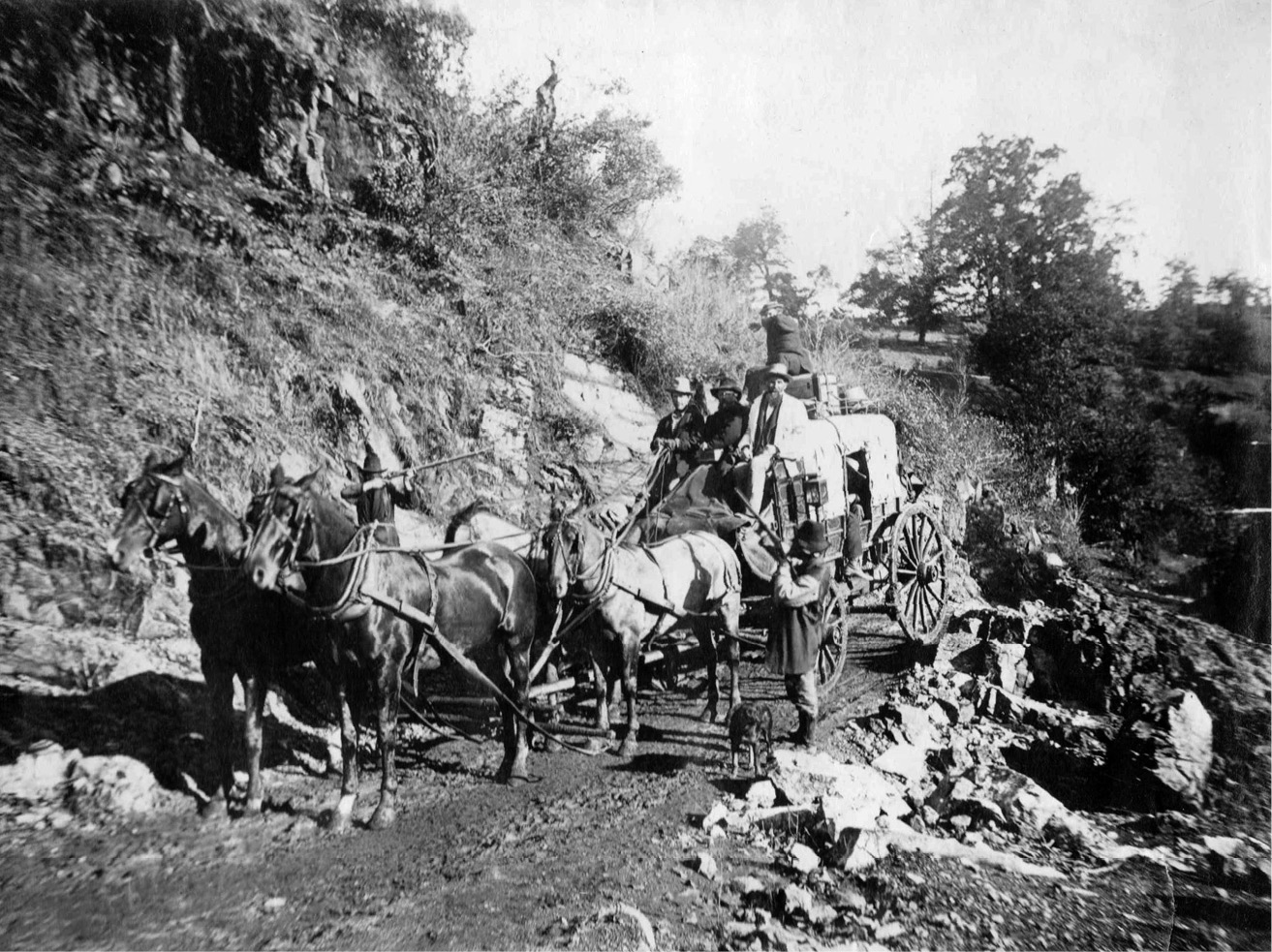

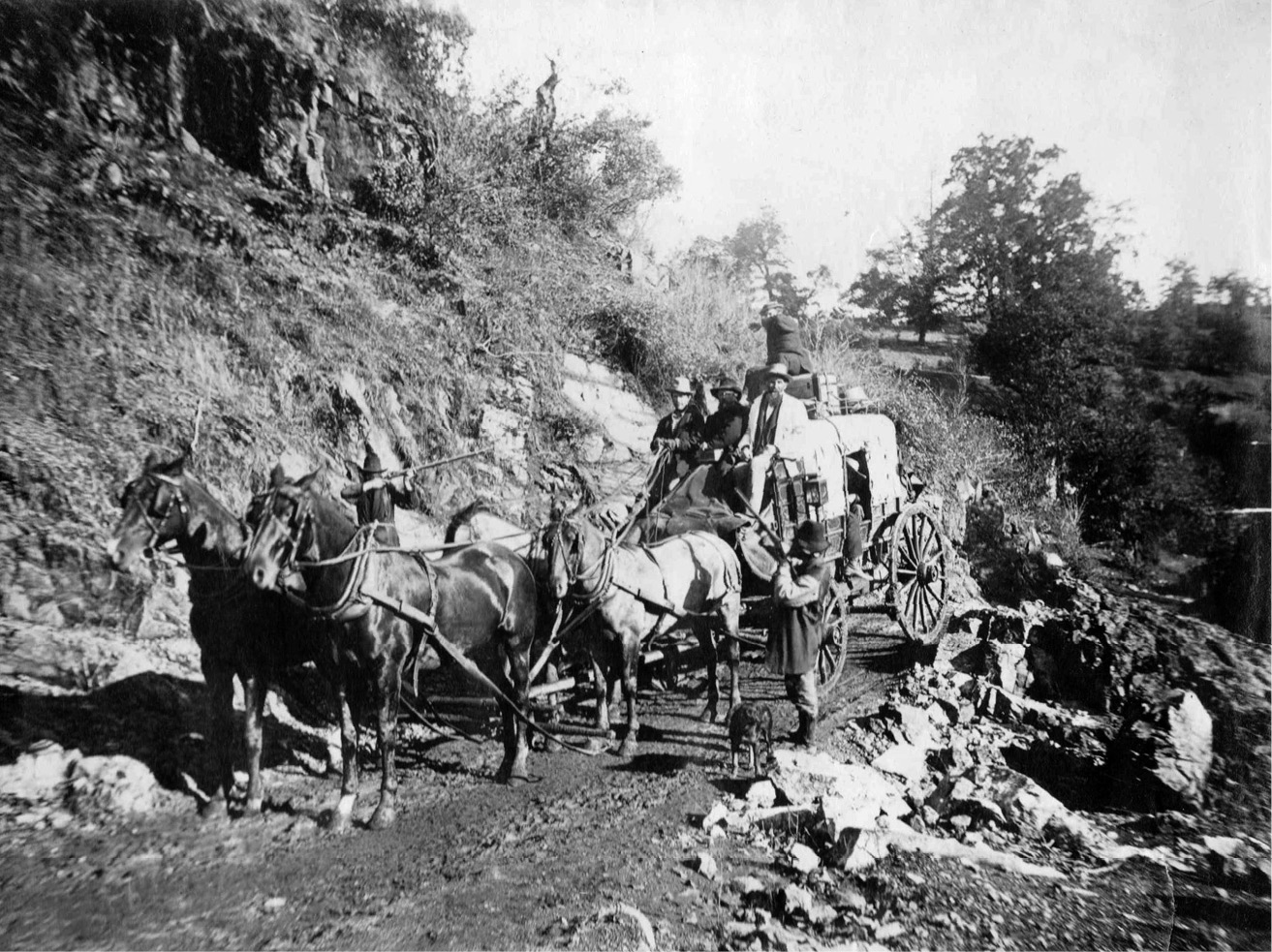

This book focuses on a time in American history when the safety and security in the eastern states was not enjoyed by those living in the wild lands of the West. How to connect the civilization of the East Coast to the rugged frontier, how to cement continental commerce, and how to form a bicoastal nation were mammoth tests for American enterprise. This challenge could not have been met without the efforts of Wells Fargo & Companys Express. And Wells Fargos mission would not have been possible without the valiant shotgun messengers and detectives who protected its treasure, its stagecoaches, and its railroad express cars.

Wells Fargo sprang to life during the California Gold Rush and came to the forefront of every successive American frontier that followed. As soon as a new mining camp or cattle town burst forth, Wells Fargo was there. The company provided both express and banking services, taking in gold and silver and shipping it out of the mining regions. Wells Fargo followed the money, and robbers followed Wells Fargo. The connection between commerce and crime was never more evident than in the story of Wells Fargo. Americas frontier regions were violent and lawless in the extreme; study after modern study has shown that to be true. As a result, Wells Fargo and the Wild West became synonymous.

To this day, the name Wells Fargo conjures up vivid images of brave shotgun guards riding atop Concord stagecoaches, battling highway robbers and mounted Indian warriors. It also brings to mind the Broadway musical and 1962 film The Music Man , and the unforgettable lyric, O-ho, the Wells Fargo wagon is a-comin down the street / Oh please let it be for me! In a few brief scenes, the iconic Wells Fargo wagon, a familiar sight to generations of Americans, came back to life. From 1852 to 1918, Wells Fargo & Companys Express was an integral part of American society. It was the perfect equivalent of todays Federal Express: Wells Fargo delivered packages to customers throughout the country and was faster and safer than the U.S. mail. The companys agents, messengers, helpers, drivers, and porters lifted, loaded, hauled, and shipped everything from small money packages to crates of fruit, poultry, merchandise, and machinery to destinations near and far. When merchants hung call cards in shop windows, Wells Fargo messengers, with their ubiquitous blue caps and black sleeve garters, stopped by in horse-drawn wagons to pick up packages for shipping. Of course, there was nothing dramatic or exciting about that. Ninety-nine percent of Wells Fargos express service was the routine delivery work so artfully re-created in The Music Man.

It was that other 1 percent that made Wells Fargo stand out from every business enterprise in American history: the companys relentless battle against thieves, highwaymen, and train robbers. Wells Fargo hired tough men who were good with guns to protect its express shipments; it employed crack detectives to unravel robberies and track down bandits. Some of the fabled characters of the Old West acted as Wells Fargo messengers, guards, or special officers: Wyatt and Morgan Earp, Bob Paul, Jeff Milton, Jim Hume, Fred Dodge, Harry Morse, and even the poet Bret Harte. But the stories of most of the companys expressmen have been long lost in the shadows of the past. Since the 1930s, many volumes have been published about Wells Fargo, but no book has ever been written about its express guards and sleuths. In the pages that follow are the true stories of twenty of the companys most valiant shotgun messengers and detectives of the Old West.

Wells Fargos story began with the discovery of gold in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada in January 1848. The news did not reach the East Coast for ten months, and when it did, all hell broke loose. Gold fever swept America and then the world as one of mankinds greatest mass migrations erupted. The gold seekers were overwhelmingly young and male, far from the settling influences of home and family. Once in Californias mining regionknown as the Mother Lodeyoung men behaved in ways they would never have dreamed of in front of their mothers, sisters, and sweethearts. They drank, gambled, whored, and brawled. With little or no law enforcement, every man was responsible for his own safety. Thus forty-niners carried bowie knives and the newly invented Colt revolver. This mixture of testosterone, alcohol, and blue steel was a deadly brew, resulting in extremely high rates of violence. The pattern set in the gold camps of California, replete with saloons, gambling halls, brothels, weak police forces, and active vigilance committees, would be followed in every successive boom frontier for the rest of the century: from the Comstock Lode in Nevada, to the gold fields of Idaho, Montana, and Colorado, to the cattle towns of Kansas, to the silver camps of Arizona, and finally to the gold mines of the Klondike.

In New York, financiers Henry Wells and William G. Fargo, two of the owners of the American Express Company, recognized that huge profits could be made in California. Their principal competitor, Adams & Co. Express, began operating on the West Coast in 1849. On March 18, 1852, they organized Wells Fargo & Company in New York, and three months later opened an office in San Francisco. Because local mail delivery was all but unknown during the Gold Rush, letters and shipments were carried by private express companies. Wells Fargo bought out these smaller concerns and rapidly expanded. By 1866, the company had 146 offices and carried express on four thousand miles of stagecoach lines. Ten years later, it had 438 offices throughout the West, operating on six thousand miles of stage lines and three thousand miles of railroad lines. As railroads expanded, so did Wells Fargo, which grew exponentially: 2,654 offices in 1890, 5,643 offices in 1910, and 10,000 offices throughout the United States in 1918. By that time, it was one of the countrys largest business enterprises, with 35,000 employees. However, wartime emergency in 1918 resulted in the federal governments merging all express companies into a single entity, American Railway Express. Although Wells Fargos lucrative banking business was unaffected, its colorful history as a pioneer express company abruptly ended.