Birley - Hadrian

Here you can read online Birley - Hadrian full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2005, publisher: Taylor & Francis (CAM), genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Hadrian

- Author:

- Publisher:Taylor & Francis (CAM)

- Genre:

- Year:2005

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Hadrian: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Hadrian" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hadrian — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Hadrian" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

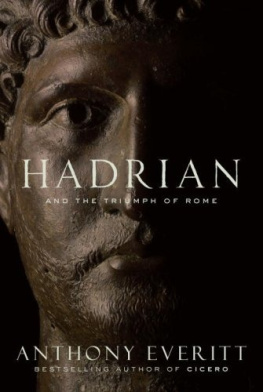

Frontispiece Bronze statue of Hadrian from Tel Shalem in Judaea. The torso may originally have belonged to a much earlier statue, of a Hellenistic king

| 1 |

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

| 15 |

| 16 |

| 17 |

| 18 |

| 19 |

| 20 |

| 21 |

| 22 |

| 23 |

| 24 |

| 25 |

| 26 |

| 27 |

| 28 |

| 29 |

| 30 |

| 31 |

| 32 |

| 33 |

| 34 |

| 35 |

| 36 |

| 37 |

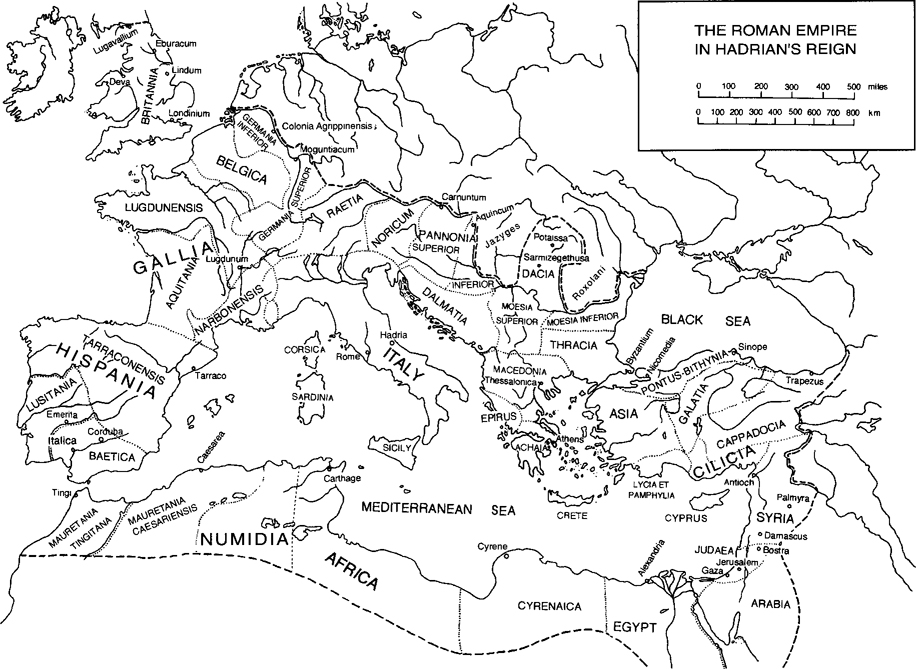

The most remarkable of all the Roman emperors: so a historian of imperial Rome described Hadrian nearly a century ago. What has mainly impressed ancient writers as well as modern students is the mans restless energy, tramping at the head of his legions through his world-wide domains, and his insatiable curiosity. He spent a good half of his reign of twenty-one years away from Rome and Italy, on the move, in virtually every province of the far-flung empire. His presence in well over thirty of them can be documented. It would be simpler to list those where he cannot be proved to have set foot: Aquitania, Lusitania, Crete, Cyprus, Cyrenaica, Sardinia-Corsica and in all but the last his presence is quite likely. Indeed, on his accession at the age of forty-one he had already spent more than half his adult life away from Rome.

This concentration on the provinces, to which the series of commemorative coins from his last years gave vivid expression, was focused partly on the armies and frontiers. He made a clear and unambiguous break with the policy of his predecessor Trajan, abandoning the newly acquired territories beyond the Euphrates immediately after his accession, then evacuating some lands beyond the lower Danube. This was followed up by the construction of a series of artificial frontier lines, of which his Wall in Britain was the most elaborate. Whether these so called limites marked a real change at the military level may be debated. Their symbolic significance cannot be overrated a clear signal to Roman traditionalists who still yearned for continuous extension of the frontiers, for an imperium sine fine. Expansion had come to an end but the Emperor was determined to maintain the army at a peak of preparedness.

The abandonment of Trajans conquests aroused hostile reaction; and, further, it was suspected that the deathbed adoption of Hadrian was a fake, stage-managed by Trajans widow Plotina in the interests of her favourite. These resentments and suspicions presumably lay behind the conspiracy as it was termed of four senior senators who were summarily put to death during the first few months of the reign. Although Hadrian claimed he had not ordered these executions, he was blamed for them and distrusted by the lite as a result. The affair of the four consulars cast a shadow over the early part of his reign. He reacted with lavish generosity, with bounty for the plebs and tax remissions and a massive building programme for the capital. This included an enormous new temple, of Rome and Venus, of which the foundation ceremony took place on 21 April 121, the birthday of Rome, on the eve of his first major tour as if to demonstrate that in spite of favours to the provinces, Rome still had a central role. A few years later he began ostentatiously to portray himself as a second Augustus.

After his extended first tour the western part, abruptly broken off in 123 when an emergency summoned him to the east, was completed with his visit to Africa in 128 Hadrians attention was devoted exclusively to the east. In the Greek-speaking half of the empire, after tentative experiments with the shrine of Apollo at Delphi as a new centre, he inaugurated an elaborate programme to make Athens a kind of second imperial capital, as the home of a new League of all the Hellenes, the Panhellenion. He seems to have seen himself as a new Pericles, bringing to fulfilment the vision which Pericles Congress Decree had supposedly striven to achieve. As the seat of the Panhellenion he chose the great Temple of Olympian Zeus, inaugurated in the sixth century BC by the Athenian tyrannos Pisistratus. It had never been completed, even though the Seleucid king, Antiochus Epiphanes, had lavishly financed its building in the second century BC . The Greeks responded to Hadrians Panhellenic programme with rapture. As the literature of the age demonstrates, they were only too eager to relive their glorious past. They conferred on him the name Olympios , once given, half in jest, to Pericles, and also the epithet of the chief god of the Hellenes.

It was not merely by completing the Olympieion that Hadrian emulated and outdid the Syrian king. Like Antiochus three hundred years before him, he sought to hellenise the Jews. This is the only plausible explanation for his prohibition of circumcision and for his conversion of the ruined Jerusalem into a colonia under the name of Aelia Capitolina, with a temple of Jupiter or Zeus to be erected over the Holy of Holies. It was an appalling misjudgement. The uprising thus provoked grew into a major war. A charismatic leader, Shimon ben Kosiba, or Bar-Kokhba, liberated a substantial part of Judaea and occupied Roman forces in a bloody struggle for three years.

In the meantime Hadrian had experienced a personal trauma. He had been married at the age of twenty-four to a distant kinswoman, Sabina, a grand-niece of Trajan. The marriage was childless and at least after two decades loveless. Hadrian was in any case more interested in males. Some time during his travels in the east he met a beautiful Bithynian boy named Antinous. He took him into his train and became besotted with him. How long the two were together is a matter of guesswork. It is legitimate to infer that Hadrian saw himself, in this as in other respects, as behaving in the tradition of classical Greece, the older man, the erastes , and the beautiful youth, the eromenos . Such relationships had always been accepted, indeed, favoured, among the Greeks. At Rome attitudes were different, although the increasing hellenisation of the upper echelons had had its effect here too, and Hadrian had been devoted to things Hellenic since his boyhood, earning the nickname Graeculus . Antinous it must be supposed was Hadrians constant companion, especially when Hadrian was indulging his passion for hunting, at least on his last great journey, beginning in late summer 128. But in October 130 Antinous was drowned in the Nile. Whether it was suicide or even some kind of sacrifice, prompted by the advice of an Egyptian priest or magician, or just an accidental death, Hadrians grief knew no bounds. The dead youth was declared a god and the Greeks, at least, responded with enthusiasm to the new cult.

Although Hadrian was able to preside at the culmination of the Panhellenic programme, the opening of the Olympieion at Athens in the spring of 132 just before the Jewish war broke out, in his last years he was something of a broken man. When he returned to Rome, at the latest in 134, his health was failing. In 136 he at last decided on a successor and adopted a young senator named Ceionius Commodus as his son and heir, giving him the new name Lucius Aelius Caesar. The choice seemed baffling and was not welcomed among the lite. Conjecture about Hadrians motives was rife at the time and modern scholars have gone even further. There was an angry reaction from Hadrians closest male relative, his grand-nephew Pedanius Fuscus. He made some move, evidently late in 137, and was put to death; his grandfather, Hadrians brother-in-law, Julius Servianus, by then in his ninetieth year, was forced into suicide. Shortly after the Fuscus affair, the new Caesar expired, and Hadrian had to find another successor. This time his selection was surer, a steady man of mature years, Aurelius Antoninus. Antoninus, in turn, was instructed to adopt the young son of Aelius Caesar, Lucius, and his own nephew by marriage, Marcus, thus ensuring the succession far ahead. It seems plausible that Marcus, now sixteen years old, had been Hadrians real choice all along, and that first Aelius Caesar, then Antoninus, were intended to keep the throne warm until Marcus was old enough to succeed. Marcus had been betrothed at Hadrians wish to the daughter of Aelius Caesar before the latters adoption; his family was related in some way to that of Hadrian; Marcus grandfather Annius Verus had been given signal honours by Hadrian; and Marcus had been a favourite of the Emperor, who was struck by his sterling qualities of character since his early childhood. The succession crisis thus reached a happy conclusion. But because of the deaths of Fuscus and Servianus, and evidently of others who had fallen out with Hadrian, including close friends, and whose deaths were laid at his door, Hadrian was deeply unpopular at the time of his death. Indeed, his remains were initially laid to rest hurriedly at Puteoli, close to where he died, for he was hated by all. Antoninus had to struggle with the Senate to carry through his deification. There would not be many who mourned him.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Hadrian»

Look at similar books to Hadrian. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Hadrian and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.