Luisa Casati, painted by Augustus John (1919).

About the Author

Judith Mackrell is the Guardians dance critic and a successful author of biographical non-fiction titles including Bloomsbury Ballerina: Lydia Lopokova, Imperial Dancer and Mrs John Maynard Keynes and Flappers: Six Women of a Dangerous Generation, which combined the stories of six women whose lives encapsulated the history of the flapper era.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

Diana Vreeland: Empress of Fashion

Louise Nevelson: Art is Life

The World of Coco Chanel: Friends, Fashion, Fame

20th Century Jewelry & the Icons of Style

See our website

www.thamesandhudson.com

CONTENTS

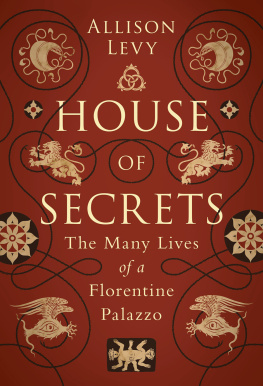

The Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in the late 20th century home of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection.

One hot evening in September 1913 a traffic jam formed on the Grand Canal in Venice, as gondolas ferrying elaborately costumed partygoers converged on the eastern stretch of the water, just as it widened out towards the lagoon. Buildings of great distinction lined the canal here, their faades glowing with the light of enormous glass chandeliers that hung from their upper stories, their magnificence reflected back at them from the waters below. Yet in the middle of this classic Venetian scene, one building obtruded like a broken tooth. Only one storey high, the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni appeared to be in a state of near-dereliction, its white stone walls overrun with ivy, its roof gaping with holes.

It was to this building, however, that the gondolas were heading. A halo of golden lights shimmered over its roof, music could be heard from its grounds and on the wide waterfront terrace a spectacular scene of greeting was in progress. Two black men, six feet tall and costumed as Nubian slaves, stood on either side of the landing steps; one of them was striking a ceremonial gong to herald the arriving boats, the other throwing metal filings onto a brazier and sending flares of white light up into the night sky. A little way behind was the partys hostess, a tall, narrow woman dressed like a Persian princess in a gauzy costume of white and gold. She stood in the centre of a wide shallow bowl filled with tuberoses; and as she received her guests she uttered no words of welcome, gave no smile of recognition, but simply bent to hand each one a single flower.

During the three years in which the Marchesa Luisa Casati had been tenant of the Palazzo Venier, she and her parties had become the stuff of local legend. Although she was by nature profoundly and eccentrically shy, she was convinced that she possessed the soul of an artist and that it was her mtier to turn herself and her surroundings into works of art. Even in a city famous for its carnivals and masquerades, there was nothing to match the theatre of the Marchesas entertainments, and all of her guests were expected to play their parts. As she stood silent and grave among the tuberoses, the men and women alighting from their gondolas on that September night were titled socialites in harem trousers, middle-aged painters with turbans and false beards a colourfully self-conscious assortment of slave girls, pashas and booted corsairs.

Oriental parties were much in vogue during this last summer before the Great War, but few had so apt a setting as this. Once the Marchesas guests had been ushered through the palazzos crumbling portico, they found themselves in a scene of improbable fantasy. In place of the gloomy marbled expanse of a typical entrance hall was a gold-coloured salon, shimmering with mirrors and noisy with the chatter of caged monkeys and parrots. Beyond the salon lay an overgrown garden in which white peacocks, pedigree greyhounds and a semi-tame cheetah roamed among gold-painted statues. As waiters in richly dyed brocade served flutes of champagne, as a black jazz band played ragtime and tango, the world Luisa had created in her palazzo that night was as elaborate, as flamboyant a meeting place of east and west as the history of Venice itself.

*****

Luisas world could not have been more different from the vision that had inspired the Venier family to commission the palazzo in the mid-18th century. The Veniers were one of the great Venetian dynasties, dating their ancestry back to the Emperors Valerian and Gallienus, whod ruled over 3rd-century Rome; they claimed to be among the earliest settlers in Venice, back in a time when it had been little more than a precarious island outpost salvaged from mud, marsh and sea.

As the city had expanded into a powerful republic, the Veniers too had risen to prominence. One of the tightly knit caste of families listed in the citys Golden Book of nobility (a register of all those qualified for high office), they had served as doges, procurators, archbishops, admirals and consuls. They had reached the apex of their glory in 1571 when their most distinguished patriarch, the Admiral Sebastiano Venier, had led the Venetian fleet to a historic victory against the Turks. Even though the admiral had been seventy-five years old when hed fought at the Battle of Lepanto even though hed had to wear slippers because his feet were so badly calloused, and had been too weak to load his own crossbow it had been Sebastianos fire that claimed the first Turkish victims, and his courage that galvanized the fleet to victory. Afterwards the admiral was lionized by a grateful city. Tintoretto painted his portrait a sage and silver-haired warrior in shining armour and he was unanimously elected Doge.

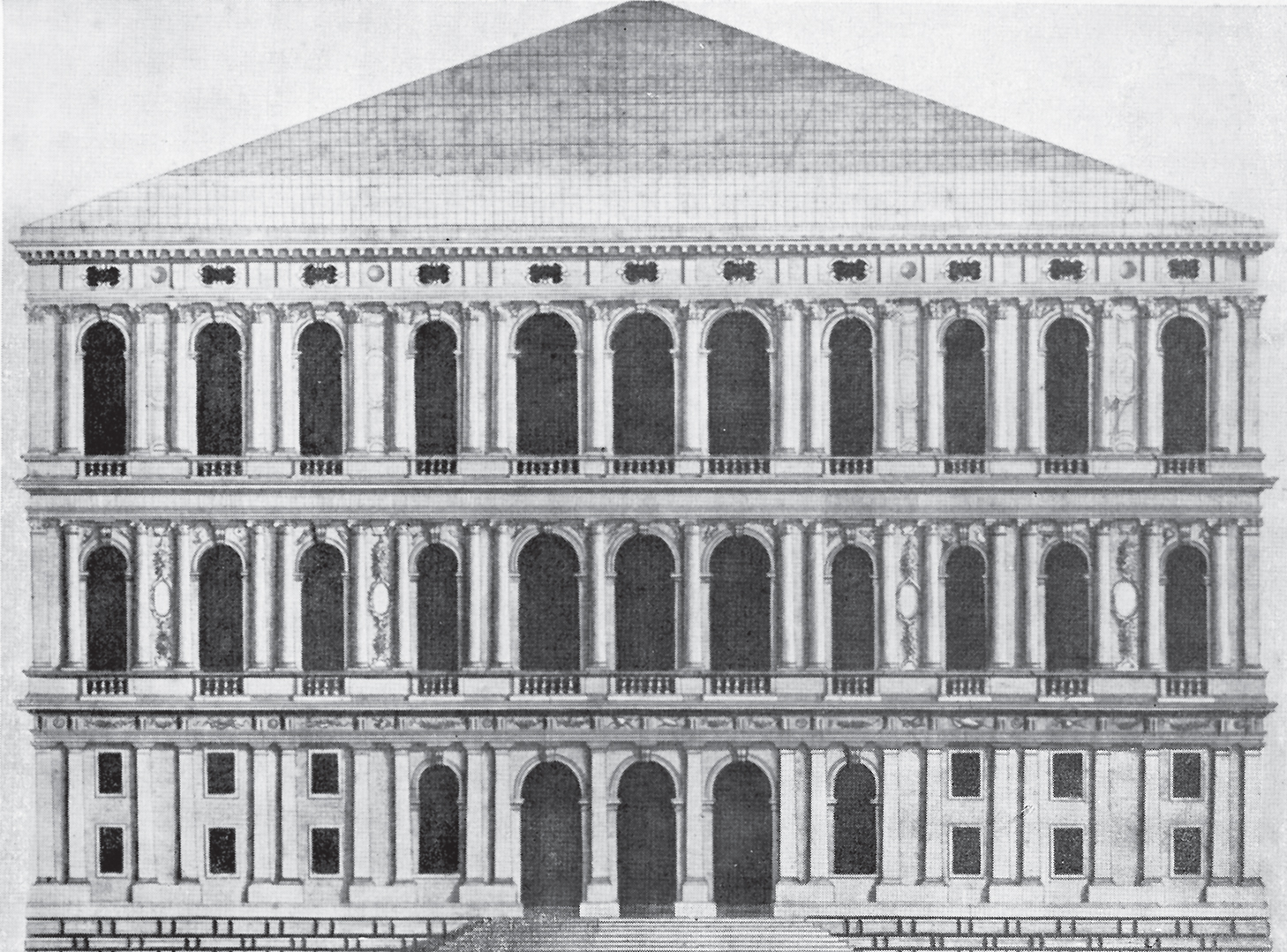

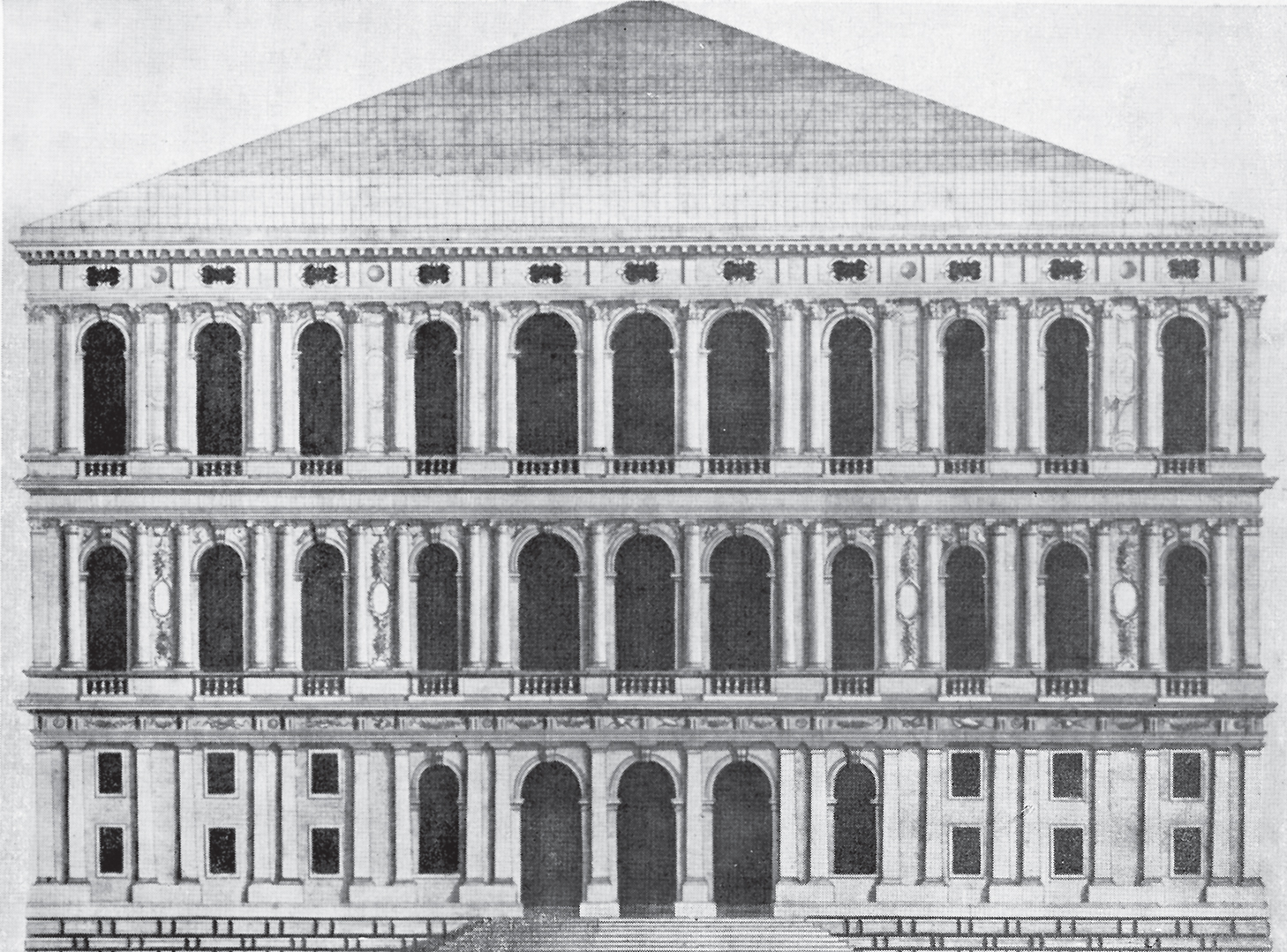

The palazzo as it was envisaged by the Venier family in the mid-18th century, a monument to dynastic pride.

The Veniers were even more successful as traders than they were as politicians, accumulating riches both within the city and beyond. If a whisper of corruption was attached to some of their enterprises, if Venier ships were rumoured to conduct illegal piratical operations on the fringes of the Venetian empire, they had money enough to redeem their reputation. Across Venice an increasing number of monuments, churches, streets and palaces began to boast the Venier name, including the old towered palazzo on the Dorsoduro bank of the Grand Canal that had been the familys principal dwelling since the mid-14th century.

By 1749, that palazzo had been subdivided to accommodate several branches of the family, and Nicol Venier and his brother were ready to expand onto the vacant plot next door. The architect Lorenzo Boschetti was hired to design a new, modern building that would make the grandest possible statement of Venier pride: a five-storey neoclassical stone palazzo with a ground floor, mezzanine, two piani nobili and an attic. It would be not only one of the tallest domestic properties on that stretch of the canal, but also the widest.

The family knew they would have to wait two, maybe three decades to see this vision materialize. There had been a short delay at the start of the project for some reason Boschetti passed it on to a more junior architect, Domenico Rizzi, and it was not until 1752 that work began on laying the foundations. Given the marshiness of the terrain, this was a complex project in itself: a forest of slender pine pilings had to be driven deep into the Venetian ooze, ready to support the thin wooden platform and brickwork on which the building would rest. Some of the workforce who laboured on site, through the summer mosquitoes, the high autumn tides and dank winter mists, would not expect to see the buildings completion. But the family Corner, who lived on the opposite bank of the canal, watched its progress with close and hostile attention. Their own palace, known locally as Ca Grande, had long dominated the neighbourhood, but as the Venier palazzo slowly rose above ground the Corners realized they were going to be overshadowed by a building of an even more arrogant scale.

Next page