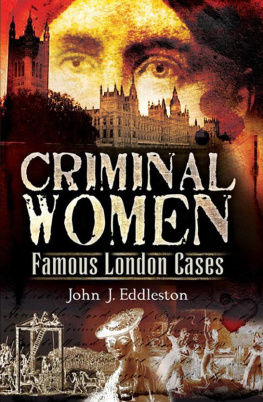

M y special thanks to the crime-writer Mark Ripper (M.W. Oldridge) for his support, expertise and invaluable assistance whilst researching this book. Also to Cate Ludlow at The History Press for her unfailing enthusiasm and understanding of the theme of the book.

The following crime-writers have been generous with their help and encouragement: Martin Edwards, Douglas dEnno, and Richard and Molly Whittington-Egan.

I am also grateful to the following for their support: Anne Dewell; Sasha and Anil Mahendra; Andy Dixon; Jim Rogers; Alan Rosethorne; Chris Horlock; Dorothy Allam; Milly Eagle; Noelle Beales; Derek Addyman; and Anne Brichto.

C ONTENTS

A vile woman, scarcely to be paralleled

Wicked beyond belief

Spiteful minx or tragic martyr?

The miserable creature in the dock

A classic serial poisoner

A truly appalling crime

M ost people find murder interesting; is it, perhaps, because the underlying passions that can result in murder are common to us all, though in the case of murderers they have become magnified, distorted and out of control? And is it our innate fear of violent death that enables us to so readily identify with the victim? Here lies the dual fascination with murder, expressed in the following words by the late lawyer and criminologist William Roughead:

Murder has a magic of its own, its peculiar alchemy. Touched by that crimson wand, things base and sordid, things ugly and of ill report, are transformed into matters wondrous, weird and tragical. Dull streets become fraught with mystery, commonplace dwellings assume sinister aspects, everyone concerned, howsoever plain and ordinary, is invested with a new value and importance as the red light falls upon each.

London is the location for the six cases of murder highlighted in this book, and each of the women involved had one thing in common they were all accused of murder or attempted murder and tried in the citys most famous courthouse, the Old Bailey. It would be impossible, in a book of this length, to highlight the many women in London who have committed equally vicious crimes, many of which may well have passed inadequately recorded, or not at all. It must be said, however, that despite the violence suffered by so many women, murders by men have always far outnumbered those committed by women.

In order to gain a little understanding of the women in this book, it is helpful to know something of the conditions in which they lived and the pressures, deprivations and limitations that dominated their lives in Georgian and Victorian London.

In 1891 it was estimated that, country-wide, more than a million that is, one in three women between the ages of fifteen and twenty were in domestic service; kitchen maids and maids-of-all work (sometimes referred to as slaveys) were paid between 6 and 12 a year. Tweenies, maids who helped other domestics, moving between floors as and when they were needed, were paid even less. There was a tax on indoor male servants and their wages were considerably higher so only the wealthy could afford to employ them. Women servants were cheap and generally more easily dominated and kept in their place. However, the close proximity of mistress and maids interdependent yet still strangers under one roof often led to squabbles and petulance especially if the mistresss expectations were too high and the maid was overworked and probably feeling alienated and homesick. Despite the potential for violent outbursts only a comparatively small number of murders were committed by servants, pushed to the limit of their endurance by the drudgery of menial work, extremely long hours and meagre pay that, and harsh treatment at the hands of their employers, sometimes led to retaliation and, in some cases, to murder.

The mistreatment of servants was commonplace, and young maids were especially vulnerable to being sexually exploited. Once hired, they found themselves in households in which a strict and unbreachable hierarchy below stairs ensured that they stayed on the lowest rung of that society. In 1740 Mary Branch and her mother were executed for beating a servant girl to death and, on the gallows, she admitted that she had considered all servants as slaves, vagabonds and thieves.

In addition to severe chastisement in their place of work, tragically, many young women in domestic service were severely punished by the law, sometimes with their lives, for giving birth to illegitimate babies. Very often, in sheer desperation, they disposed of these new-borns in privies, ditches and on dung-heaps and when found out, were tried by male judges and jurors. Although some were treated mercifully, others were hanged for their actions.

The briefest study of court records, the Newgate Calendar , contemporary newspaper reports or similar publications clearly illustrates the extent of the violence regularly meted out, not only to servants but also to women and children, by fathers, husbands and lovers. The ineffectual, amateur and largely unaccountable law enforcers, who were open to bribery and corruption; the ducking and diving to dodge the law in order to make some sort of living, one way or another; illiteracy, which made record-keeping random and incomplete; the frequency of premature death of women in childbirth, and the high mortality rate amongst infants all these factors helped to mask and conceal criminal activity, even murder.

The alternative to a life of domestic drudgery for many women, ranging in age from those in early pubescence to those well past middle-age, was prostitution, especially for those females raised in institutions and without family support. Some were unable to find husbands to support them, whilst others may have been unwilling to become a chattel for life.

Domestic service was a precarious living, as girls could be sacked immediately for breaking house rules or committing some other misdemeanour. Once employed, young women would arrive with their boxes, containing their work clothes and undergarments, possibly a Bible and perhaps a few personal mementos of their lives before entering service. If a maid displeased her mistress, her box might well be retained after dismissal possibly to make up a deficit from real or imagined thieving. However, without a box and a character, a written recommendation or reference, it was extremely difficult to find another position. Without the prospect of further employment some servants chose to become prostitutes; others, whilst still in domestic employment, would sometimes offer themselves in return for trinkets and small gifts these were known as dolly mops.

A few cases have been recorded of a client frequenting a brothel only to be confronted by either his cook, his childrens nanny she had ample opportunity to attract admirers whilst pushing infants in perambulators through Londons parks and pleasure gardens or a parlour maid, supplementing her meagre wages with a little dolly mopping on the side. The mutual embarrassment can be imagined.

The number of prostitutes working in London in the nineteenth century was estimated at many thousands but, by its nature, the sex trade was clandestine, transitory and exploitative and it was therefore impossible to arrive at a true figure. With so many prostitutes at work in the city, perspective clients could purchase catalogues listing the women and their specialities available for hire, in Harriss List of Covent Garden Ladies and other similar publications. Those at the top of the pile, sometimes referred to as either gay women or unfortunates, paraded in their brightly coloured clothing but without hats around the theatres along the Strand, Haymarket, and Covent Garden; the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens were also extremely popular for business. But many more, women who were perhaps less appealing, were reduced to standing on murky street corners and wandering the dark alleys between the squalid tenements in the poorer districts of the city, plying their trade as best they could, and, as often as not, vulnerable to violent attack.

Next page