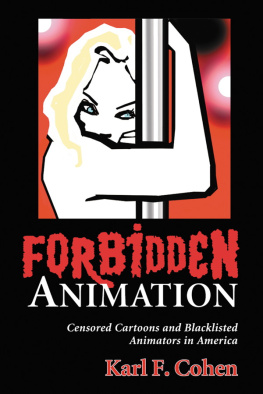

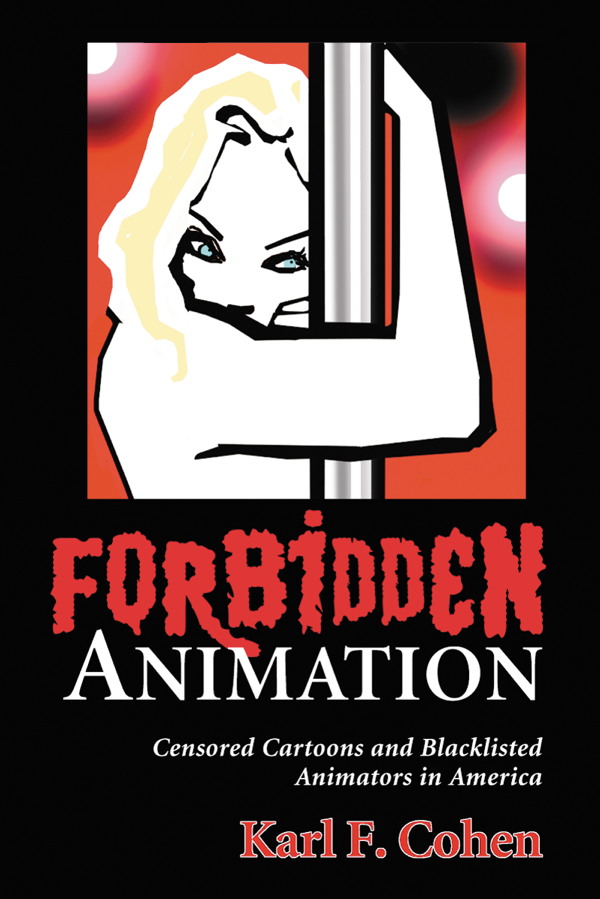

Forbidden Animation

Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America

by

Karl F. Cohen

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina, and London

The present work is a reprint of the library bound edition of Forbidden Animation: Censored Cartoons and Blacklisted Animators in America, first published in 1997 by McFarland.

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

e-ISBN 978-1-4766-0725-2

1997 Karl F. Cohen. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: 2004 Image Zoo

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

This book is dedicated

to Denise McEvoy Cohen

my loving wife

Preface

I have always been a fan of animation, but while growing up I simply saw the medium as a form of entertainment that I loved. It was not something anybody bothered to discuss when I was a college student studying film and art history in the 1960s. As a professional art historian in the 1970s my interest in animation grew, and I began to dedicate more time each year to seeking out interesting works and reading what little existed on the subject. Finally, in the mid-1970s, I began to meet the people who created the medium, and through them I learned some of its untold history. Thanks to Ron Hall I subscribed to Mindrot, probably the nation's first animation fanzine. I began to write short articles about the medium for magazines including Filmmakers Newsletter, Mindrot and much later Animatrix, Animation Journal, Animation Magazine, Animato!, InToon! and the Frostbite Falls Far Flung Flyer. (Funny World could also be considered the first animation fanzine, but it covered comics and other forms of popular culture and was modeled after a quality magazine. Mindrot considered itself the "Animated Film Quarterly.")

My awareness that animation could be risque and could provoke censorship came in 1973 when I was running a weekly film and vaudeville series in San Francisco. Mary Meyer-Lucas, a North Beach art dealer, said that she had heard about a Betty Boop cartoon that had been taken off the screen while it was being shown at a community hall in Hawaii. Apparently the projectionist or theater manager saw something in the film that he or she thought should not be shown to the public. Meyer-Lucas asked me if I could find the film and screen it. She wanted me to show her something too hot to be shown. We never found out what the cartoon was, but I became a Betty Boop fan while searching for this forbidden treat, and I enjoyed seeing a number of the naughty pre-code Betty Boop cartoons.

As I met more people in the animation industry, my knowledge of the forbidden side slowly grew. Censorship of cartoons was a subject that books and magazine articles ignored, but animators enjoyed talking about different cases from time to time. At first I simply listened. In the late 1980s I began, occasionally, to ask people about censorship when I was interviewing them for articles about other topics. When I wrote my first article on the subject, a Society for Animation Studies conference paper presented at CAL Arts in 1992, everything I knew about censorship filled about 15 or 20 pages.

The history of "forbidden" animation also includes work the public was unable to see because the animators were censured. Sometimes this censure was the result of union activities. Sometimes animators were suspected of Communist sympathies and blacklisted. Labor history has been a lifelong interest for me, and blacklisting had a personal resonance too: I had two relatives who lost jobs in the early 1950s when the FBI tipped off their bosses that they had hired men with "questionable" political pasts. (FBI files on these men reveal that the worst thing one did was to disrupt a concert of a black artist performing for an all-white audience in the 1940s. He marched into the segregated hall with an African-American woman and demanded seats. Both relatives had been arrested in a sit-in demonstration in New Mexico in the 1930s. The issue was the state's almost nonexistent welfare program.) In the 1980s I met David Hilberman, an animator who was blacklisted in the 1950s, and I was inspired to begin research on blacklisting in the animation industry. In 1992 my first article on the subject, "Witch Hunt in the Magic Kingdom: The Investigation of Alleged Communists in the Animation Industry," appeared in Animatrix, a journal from the University of California-Los Angeles Animation Workshop.

Much of the material in this book has never before been published. It is based on interviews with animators, producers and animation scholars and countless hours of library research going over historical documents. These primary sources have been checked and rechecked to insure as much accuracy as possible. Some material of questionable authenticity has been left out, and alternate versions of some stories are included when a definitive version could not be established.

Three animation scholars have read the entire text for errors, omissions, and other problems. (Any errors that remain are of course my fault.) They have made helpful suggestions and provided additional information for each chapter. One of the scholars is John Canemaker, an animator, the head of New York University's animation department, and the author of numerous articles and books (including books on Disney, Tex Avery, Felix the Cat, Winsor McCay and a Richard Williams feature). The second is Jerry Beck, who has authored several books that are mentioned in this work. Beck is presently a vice president of Nickelodeon, for whom he is developing animated features. The third scholar is Mark Kausler, an animator at Disney who has spent much of his life talking with artists and seeing almost every cartoon ever made. Amazingly, he remembers almost every detail of every film and is a walking encyclopedia of animation information. In addition to Canemaker, Beck, and Kausler, several other people mentioned in the book have read parts of it and have provided valuable improvements to the text.

Improving my writing skills has been an ongoing study over the course of my professional life. My first wife, Donna, who died in 1979, was my first real teacher. She helped me get through my thesis at the University of California-Berkeley and proofread dozens of articles when I began my work as an art historian. Maria Elena Rodriguez was my second great teacher. She edited several issues of Animatrix at UCLA and taught me a great deal about style, organization skills, and other basics. I am also indebted for the help I have received from Maureen Furness of Animation Journal; from Dr. Harvey Deneroff, when he was editor of Animation Magazine; from Steve Goldstein and Jenny Boone of Film/Tape World; and from Pete Davis, who has proofread numerous issues of the monthly ASIFA-San Francisco newsletter that I write.

This book cannot cover the entire history of censorship in animation, because the story is still unfolding. It is a strange story that may become stranger as the United States heads toward having 500 television channels. As for the information on labor strikes and blacklisting, there is probably enough still unlearned to make up a large book on the subject. I also expect to learn more about the elimination of racial stereotypes in the coming years.

Next page