This Is a Borzoi Book

Published by Alfred A. Knopf

Copyright 2011 by Rodney Crowell

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Opus 19 Music Publishing for permission to reprint an excerpt from Baby What You Want Me to Do by Jimmy Reed. Reprinted by permission of Opus 19 Music Publishing.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Crowell, Rodney.

Chinaberry sidewalks / by Rodney Crowell.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-307-59521-8

1. Crowell, Rodney. 2. Country musiciansUnited States

Biography. I. Title.

ML420.C956A3 2011

782.421642092dc22

[B] 2010035996

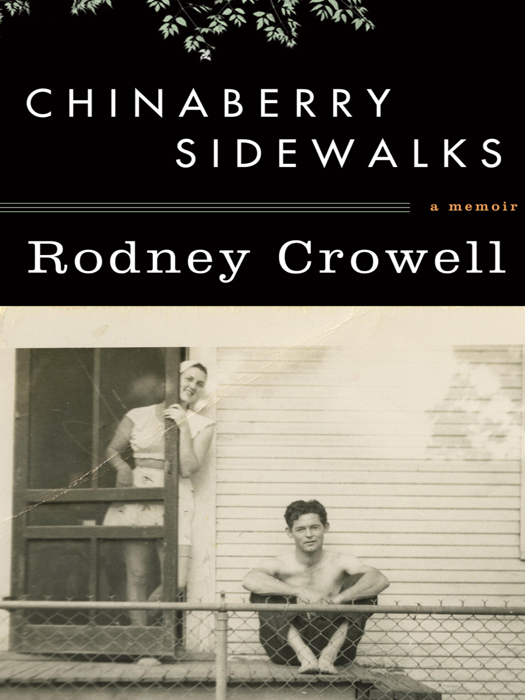

Jacket photograph courtesy of the author

Jacket design by Joe Montgomery

v3.1_r1

For my children and their children

Contents

New Years Eve, 1955

T he four beer-blitzed couples dancing in the cramped living room of my parents shotgun duplex were wearing on my nerves. In particular, I didnt like the sound of their singing along with my prized Hank Williams 78s. Coon hunting with my grandfather, Id heard bluetick hounds howl with more intonation than this nasal pack of yahoos. For a while I tried contenting myself with sticking my fingers in my ears and staring squinty-eyed at the scuffmark patterns forming on the linoleum, hoping a likeness of Jesus or Eisenhowerthe only famous images I knew of at the time other than ole Hank, as my father and I referred to our favorite singerwould stare up at me from beneath the dancers feet. But when all I could summon up was a swarm of black stubby snakes, I gave up and went back to being in a funk.

The next thing I remember, Cookie Chastain was screeching to be heard above the scratchiness of whichever record shed just gored with the blunt end of the phonograph needle. Twenty minutes till midnight. Everybody change partners. And while the rest of the gang bumped around and groped for whom to dance with next, she was making a big deal out of sashaying into the waiting arms of the one man whose lust for oblivion I knew could turn this little shindig into a repeat of my worst nightmare. By then Id guzzled most of the six-pack of Cokes Id discovered in the icebox and was no longer ready to pretend that this New Years Eve nonsense was anything but a recipe for disaster. My mother was mad as a hornet, but too ashamed to make a scene just yet; Mr. Chastain and the others were too wasted to notice or care; and my father, the only real singer in the bunch, had once again lowered his standards to a level that guaranteed trouble.

Id been privy to the shadowy undercurrents detailed in my mother and fathers all-night shouting matches long enough to know that drunk husbands and wives swapping two-steps with other drunk wives and husbands, though a time-honored Texas tradition, was anything but harmless fun. I could never grasp what she accused him of doing with Lila May Strickland or Pauline Odell, but I knew by her disdain for the word screwing that nothing good ever came of the deed. And it got more complicated when she started screaming about how hed even screw a light socket if one could spread its legs for him. Grown-ups were weird.

Unlike my father, I was beginning to understand that all this business about who or what he was supposedly screwing served a darker purpose for my mother: setting up yet another reprise of the brain-scalding accusation that hed belt-whipped her across the belly when, eight months pregnant with me, she stood naked in the bathtub.

The scene is seared in my mind as if Id actually been able to witness it. A sliver of July dusk creeps in under the canvas window shade, and the dangling circle on the end of its pull string is tapping against the yellowed wallpaper beneath the sill. On the back of the door, an ancient hot-water bottle gives off traces of vinegar douche, mementos from a time before I entered the picture. Theres the buck-stitched cowboy belt and fake trophy buckle; for years I imagined a silver-headed rattlesnake in the grip of an escaped convict, though Ive yet to conjure how he managed, in a space half the size of a prison cell, to wield the thing. And veiled in a sepia gauze, courtesy of the light fixture above the medicine cabinet, is my mother, naked as Eve, dripping wet and cowering in the claw-footed tub, stillbirth emblazoned across her frontal lobe. But whose memory is this in which I can see these things so clearly yet cant place my father? His? Hers? Or mine?

I despised my mothers need to belittle my father in my eyes as much as I hated his refusal to deny wielding this belt. To accept her version as fact, which I did, and never believing his trademark Aw, hell, Cauzette, you know I did no such a thing meant embracing the possibility that it could all happen again. Together, my parents made it impossible to keep my father on the pedestal where I needed him most. And about that, all I can tell you is this: Id be well within range of the truth if I said there were times I was mad enough to kill them both.

Id been sleeping in the living room longer than I could remember, my mother making a nightly ritual of fixin up a pallet on the sofa. In the early days, the kitchen chair she positioned to keep me from rolling off onto the floor simulated a perfectly good crib. Still, the shame of my not having a bedroom of my own was particularly hard on her. Other than dying and going to heaven, the dream of a nursery for her only living child was her lone investment in the promise of a better future. As far as I was concerned, this was a waste of wishful thinking; I much preferred my arrangement on the couch to the mildewed cave that was the front bedroom.

Conditions surrounding my parents beer-and-baloney soiree made the crossing of some invisible line in their ongoing war of hard words and physical abuse a foregone conclusion. As much as I hated the discomfort of having my territory invaded by mindless adults, I dreaded even more my inability to escape the hellish crescendo I knew would follow when my father started chasing beer with whiskey.

But no refuge was to be found in the front bedroom, whose dark shadows and damp spookiness scared me witless. Wallpaper hung from the ceiling in stained, ragged strands, like a cross between witch hair and brown cotton candy. The jaundiced glow of the exposed overhead lightbulb fell far short of its four corners, where untold evil lurked. Should I find myself alone in that room, the cardboard windowpanes, creaky floors, and lumpy thirty-year-old mattress were the least of my worries.

Traffic to and from the partys beer supply rendered the kitchen in back of the house a useless hideout, likewise the bathroom where I could have played with my toy cars on the floor. Left to idle in the narrow hallway between the living room and the bedroom, I began to hatch a plan.

My intention to break up the party, before it reached the point that my parents had time and again proven themselves unable to return from without inflicting damage, didnt necessarily include subjecting their guests to bodily harm. I liked Doc and Dorothy Lawrence, Pete and Wanda Faye Conn, Paul and Cookie Chastain as sober adults. Just the same, the job of saving my parents from themselves called for drastic measures, and innocent bystanders couldnt be helped.