Copyright 2014 by Lawrence Goldstone.

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books,

an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group,

a division of Random House LLC, a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

B ALLANTINE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

All photos courtesy of the Library of Congress

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING - IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Goldstone, Lawrence, 1947

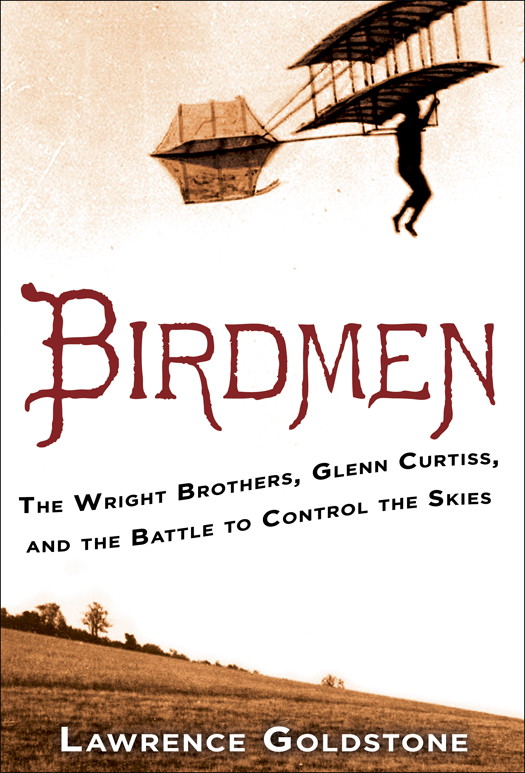

Birdmen : the Wright Brothers, Glenn Curtiss, and the battle to control the skies / Lawrence Goldstone.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-0-345-53803-1 (hardcover : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-345-53804-8 (eBook)

1. AeronauticsUnited StatesHistory. 2. Wright, Wilbur, 18671912.

3. Wright, Orville, 18711948. 4. Curtiss, Glenn Hammond, 18781930.

I. Title.

TL521.G568 2014

629.130092273dc23 2014001424

www.ballantinebooks.com

Jacket design: David G. Stevenson

Jacket photograph: The Library of Congress

Title page image by Gzde Otman

v3.1

Inherently Unequal: The Betrayal of Equal Rights by the Supreme Court, 18651903

Dark Bargain: Slavery, Profits, and the Struggle for the Constitution

The Activist: John Marshall, Marbury v. Madison, and the Myth of Judicial Review

The Astronomer

The Anatomy of Deception

Off-Line

Rights

With Nancy Goldstone

Out of the Flames: The Remarkable Story of a Fearless Scholar, a Fatal Heresy, and One of the Rarest Books in the World

The Friar and the Cipher: Roger Bacon and the Unsolved Mystery of the Most Unusual Manuscript in the World

Deconstructing Penguins: Parents, Kids, and the Bond of Reading

Used and Rare: Travels in the Book World

Slightly Chipped: Footnotes in Booklore

Warmly Inscribed: The New England Forger and Other Book Tales

With Vernona Gomez

Lefty: An American Odyssey

For Nancy and Emily

Genius Extinguished

At 3:15 A . M . on May 30, 1912, Wilbur Wright died peacefully in his own bed in the family home at 7 Hawthorn Street in Dayton, Ohio, surrounded by his father, Milton; his sister, Katharine; and his three brothers, Lorin, Reuchlin, and Orville. Wilbur had contracted typhoid fever one month earlier from, the speculation went, eating tainted clam broth in a Boston restaurant. At five feet ten and 140 pounds, his body had lacked the strength to fight off an ailment that in the coming decades would be routinely vanquished with antibiotics. He was forty-five years old.

America had lost one of its heroes, one of two men to solve the riddle of human flight, and messages of praise and condolence poured into Dayton from around the world. More than one thousand telegrams arrived within twenty-four hours of Wilburs death. President William Howard Taftwho at 350 pounds could never himself be a passenger in a Wright Flyer, although his predecessor Theodore Roosevelt had beenissued a statement declaring Wilbur to be the father of the great new science of aeronautics, who would be remembered on a par with Robert Fulton and Alexander Graham Bell. Aeronautics magazine exclaimed, Mr. Wright was revered by all who knew him, he was honored by an entire world, it was a privilege, never to be forgotten, to talk with him.

Across the nation, newspapers and magazines decried the sad stroke of luck that had robbed the nation of one of its great men. At 7 Hawthorn Street, however, members of the Wright family did not believe Wilburs death to have been a result of bad luck at all. To them, Wilbur had been as good as murdered, hounded to his grave by a competitor so dishonest, so unscrupulous, so lacking in human feeling as to remain a family scourge as long as any of them remained alive.

Glenn Curtiss.

The bitter, decade-long WrightCurtiss feud pitted against each other two of the nations most brilliant innovators and shaped the course of American aviation. The ferocity with which Wilbur Wright attacked and Glenn Curtiss countered first launched America into preeminence in the skies and then doomed it to mediocrity. It would take the most destructive conflict in human history to undo the damage.

The combatants were well matched. As is often the case with those who despise each other, Curtiss and Wilbur were sufficiently alike to have been brothers themselves. Both were obsessive and serious, and one is hard-pressed to find a photograph of either, even as a child, in which he does not appear dour. Wilbur Wright was the son of a minister, Curtiss the grandson of one. Wilbur was the grandson of a carriage maker, Curtiss the son of a harness maker. Each came to aviation via the same routeracing, repairing, and building bicyclesand each displayed the amalgam of analytic instincts and dogged perseverance that a successful inventor requires. Most significant, neither of these men would ever take even one small step backward in a confrontation.

They may have been alike, but they were not the same. Wilbur Wright is one of the greatest intuitive scientists this nation has ever produced. Completely self-taught, he made spectacular intellectual leaps to solve a series of intractable problems that had eluded some of historys most brilliant men. Curtiss was not Wilburs equal as a theoreticianfew werebut he was a superb craftsman, designer, and applied scientist. In physics, he would be Enrico Fermi to Wilburs Albert Einstein.

After Wilburs death, Orville attempted to maintain the struggle, but while his hatred for Curtiss matched Wilburs, his talents and temperament did not. Many subsequent accounts have treated the Wright brothers as indistinguishable equals, but Orville viscerally as well as chronologically never ceased being the little brother. As family correspondence makes clear, his relationship with Wilbur was a good deal more complex than is generally assumed and after his brothers death, Orville was never able to muster the will to pursue their mutual obsessions with the necessary zeal.

Curtiss, who often spoke of his speed craving, first turned his attention to propulsion. He experimented with motorizing bicycles and in January 1907 set a one-mile speed record of 136.7 miles per hour, for which he was hailed as the fastest man on earth; two years later, he would also be the fastest man aloft. By the time the Wrights, after a three-year delay, finally decided to aggressively market their invention, Curtiss was engineering the most efficient motors in the world. That he would mount those motors on aircraft created a threat to the Wrights aspirations of monopoly and they brought suit to stifle the upstart. Although the Wrights never ceased to insist that their unrelenting pursuit of Curtiss was a moral issue, it was, as is virtually all such litigation, about money.

But for all the maneuvering and legal gamesmanship, the WrightCurtiss feud was at its core a study of the unique strengths and flaws of personality that define a clash of brilliant minds. Neither Glenn Curtiss nor Wilbur Wright ever came to understand his own limits, that luminescent intelligence in one area of human endeavor does not preclude gross incompetence in another. And because genius often begets or even requires arrogance, both men continuously repeated their blunders.