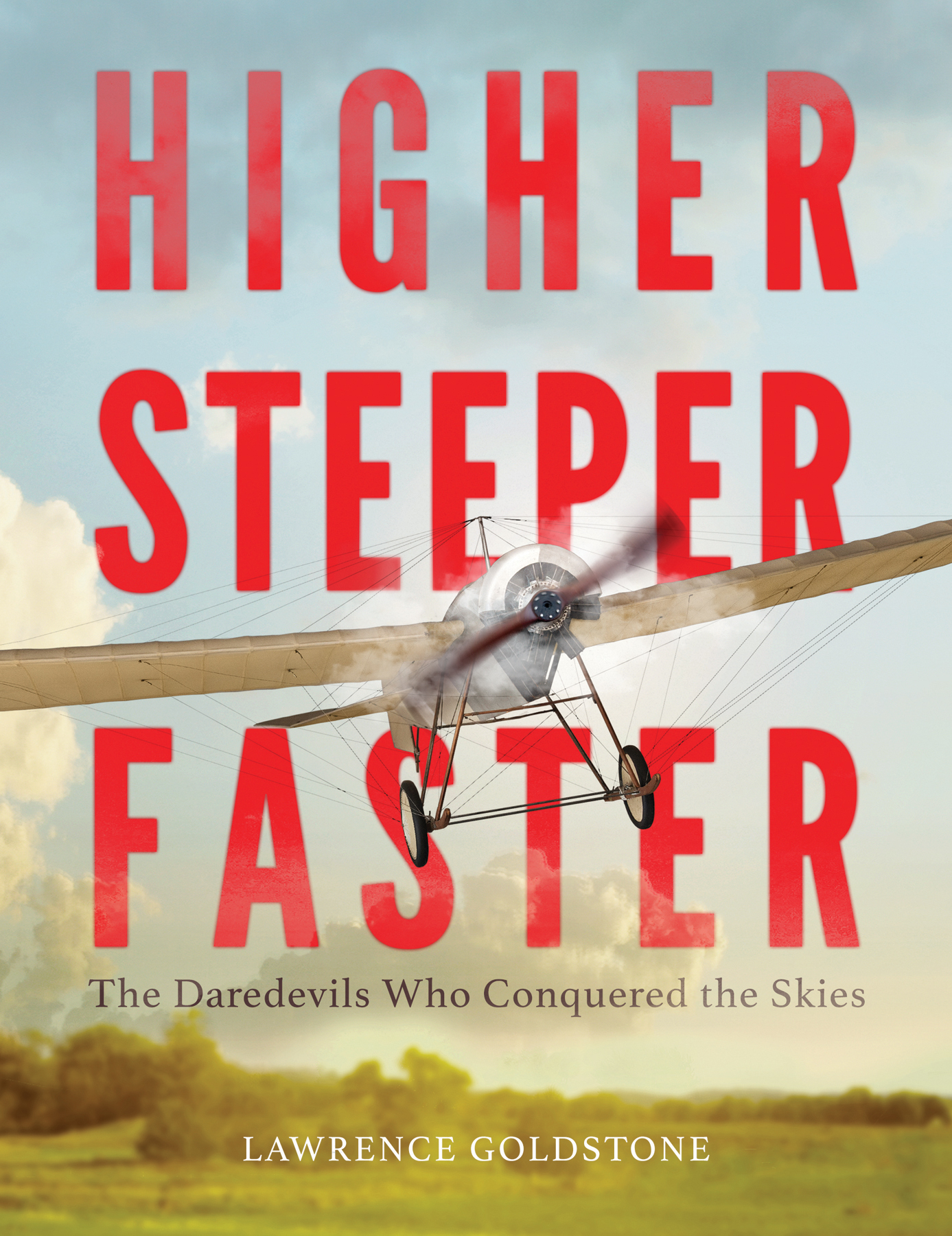

Copyright 2017 by Lawrence Goldstone

Cover art copyright 2017 by Larry Rostant. Cover design by Sasha Illingworth.

Cover copyright 2017 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

Visit us at lb-kids.com

First Edition: March 2017

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Airplane image on title and chapter pages jekson_js/Shutterstock.com

Image credits can be found throughout. No credit is included for images in the public domain.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Goldstone, Lawrence, 1947 author.

Title: Higher, steeper, faster : the daredevils who conquered the skies / Lawrence Goldstone.

Description: First edition. | New York : Little, Brown and Company, [2017] | Audience: Ages 8 to 12. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016016576| ISBN 9780316350235 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780316350228 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Air pilotsHistoryJuvenile literature. | DaredevilsHistoryJuvenile literature. | Air pilotsBiographyJuvenile literature. | DaredevilsBiographyJuvenile literature. | FlightHistoryJuvenile literature. | AeronauticsHistoryJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC TL547 .G64 2017 | DDC 629.13092/2dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016016576

ISBNs: 978-0-316-35023-5 (hardcover), 978-0-316-35022-8 (ebook)

E3-20170307-JV-PC

To Nancy and Lee

March 14, 1915. San Francisco, California

F ifty thousand people sat in the grandstand of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, facing the bay, and perhaps one hundred thousand more lined the waterfront. The Panama-Pacific was the biggest, most important event ever staged in San Francisco, a worlds fair to announce that the city had finally recovered from the terrible 1906 earthquake.

Millions would come to see its attractions: walk-through replicas of Yellowstone National Park and the Grand Canyon, a five-acre working model of the Panama Canal, the actual Liberty Bell, on loan from Philadelphia. The Ford Motor Company had set up an assembly line and for three hours a day would build an automobile every ten minutes. Fairgoers could watch hula dancers, ride a miniature railway or a submarine, or sit in a compartment on a swing arm that propelled those inside to and fro over the grounds. There was even a 435-foot-high Tower of Jewels, decorated with more than one hundred thousand pieces of polished colored glass, called Novagems, imported from Europe and strung on wires. Fifty colored spotlights shone on the tower each night, making it visible in every corner of what was now known as the Jeweled City. For local children, many of whom lived without plumbing or electricity, the fair was a door to another world.

But on this day, those thousands and thousands of people had not come to see automobiles, submarines, the Liberty Bell, or even a jeweled tower that seemed to stretch all the way to the heavens.

They had come to see a man attempt the impossible. They had come to see Lincoln Beachey fly.

In a hangar, out of sight of the crowd, Beachey checked his airplane. He was a short man, only five feet seven inches, and stocky, with a shock of red hair. Just eleven days before, he had celebrated his twenty-eighth birthday. He was wearing his trademark flying outfita pin-striped suit, a two-carat diamond stickpin in his cravat, and a peaked cap that he would turn backward before taking off. In public, Beachey always appeared serious, all business. Few could remember ever seeing him smile.

Beachey pulled at one of the thin cables that braced the wing to the fuselage. He would check every piece of every airplane in which he flew, but never more closely than today. It was taut, with no give. Just right.

And it would have to be just right. This day, Lincoln Beachey was to attempt a feat of flying that no man or woman had tried before, one so dangerous that other flyers had begged him not to try.

But Lincoln Beachey hadnt become the greatest, most celebrated aviator in the world by shrinking from danger. In the United States, he was a better-known figure than President Woodrow Wilson. In a country with a population of almost eighty million people, it had been said that more than twenty million Americans had seen Lincoln Beachey work his magic in the skies above them. For his incredible flying, he made more money in one day than most Americans earned in a year. Reporters called him the Master Birdman, or the Man Who Owns the Sky.

He had gained those accolades through a series of daring and harrowing maneuvers. Four years earlier, at the great Chicago International Aviation Meet of 1911, the highest anyone had ever flown was 11,150 feet, and Beachey had been determined to claim the record for himself. But there was only one way to do so. He would need to use all his fuel on the way up. That would leave him in the thin, freezing air with no way down but to glide more than two miles in the strong, swirling winds over Lake Michigan, left totally to the mercy of crosscurrents and updrafts. Flying without powercalled dead-stickingwas one of the most difficult maneuvers any flyer could attempt. Doing so from as low as two hundred feet takes incredible skill. From eleven thousand feet, coming in over water, where the tiniest error meant losing control and plunging to certain death, it was considered impossible. No other person on earth would consider such a stunt.

And the airplane Beachey was to take aloft wasnt even really an airplane at all; at least not the way we would think of one today. It was just a frame, totally open, with wings, a motor, a rudder, and a seat. There was nothing to protect him from the terrible cold and wind at higher altitudes, or to cushion him from jolts worse than the bucking of a bull in a rodeo. Early airplanes had no instruments, not even a fuel gauge to tell flyers when fuel was running out; nothing to tell them where they were, or how high, or if something had gone wrong with the motor. And if something did go wrong, there was no way to communicate with the ground. All that protected Beachey and aviators like him from horrible death was their own skill and experience.

For many, that was not enough.

At five thirty PM on August 20, 1911, Beachey got into his airplane. The crowd of 350,000 people fell silent. There was no one else in the airevery eye was focused on him. Beachey took off easily and ascended steadily, first in circles around the borders of Grant Park and then and then over the lake. With the sky totally clear, Beachey was never out of eyeshot of the ground. Eventually, his airplane seemed no larger than a speck in the sky. But then, after a few moments, the speck began to grow larger. Soon it had taken shape enough for those on the ground to see that, indeed, his propeller was not moving! He had used all his fuel.