JZEF CZAPSKI (18961993), a painter and writer, and an eyewitness to the turbulent history of the twentieth century, was born into an aristocratic family in Prague and grew up in Poland under czarist domination. After receiving his baccalaureate in Saint Petersburg, he went on to study law at Imperial University and was present during the February Revolution of 1917. Briefly a cavalry officer in World War I, decorated for bravery in the Polish-Bolshevik War, Czapski went on to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakw and then moved to Paris to paint. He spent seven years in Paris, moving in social circles that included friends of Proust and Bonnard, and it was only in 1931 that he returned to Warsaw, and began exhibiting his work and writing art criticism. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Czapski was mobilized as a reserve officer. Captured by the Germans, he was handed over to the Soviets as a prisoner of war, though for reasons that remain mysterious he was not among the twenty-two thousand Polish officers who were summarily executed by the Soviet secret police. Czapski described his experiences in the Soviet Union in several books: Memories of Starobilsk (forthcoming from NYRB), Inhuman Land, and Lost Time (available from NYRB), the last of which reconstructs a lecture he gave to his fellow prisoners about Prousts In Search of Lost Time. Unwilling to live in postwar communist Poland, Czapski set up a studio outside of Paris. His essays appeared in Kultura, the leading intellectual journal of the Polish emigration that he helped establish; his painting underwent a great final flowering in the 1980s. Czapski died, nearly blind, at ninety-six. Almost Nothing: The 20th-Century Art and Life of Jzef Czapski, a biography of Czapski by Eric Karpeles, was published by New York Review Books.

ANTONIA LLOYD-JONES is the 2018 winner of the Transatlantyk Award for the most outstanding promoter of Polish literature abroad. She has translated works by several of Polands leading contemporary novelists and writers of report-age, as well as crime fiction, poetry, and childrens books. She is a mentor for the Emerging Translator Mentorship Programme and former co-chair of the Translators Association of the United Kingdom.

TIMOTHY SNYDER is the Richard C. Levin Professor of History at Yale and a permanent fellow of the Institute for Human Sciences in Vienna. He is the author of several works of European history, including Bloodlands, winner of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Literature Award, the Hannah Arendt Prize, and the Leipzig Book Prize. His most recent books are On Tyranny and The Road to Unfreedom.

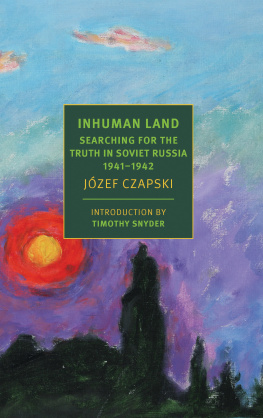

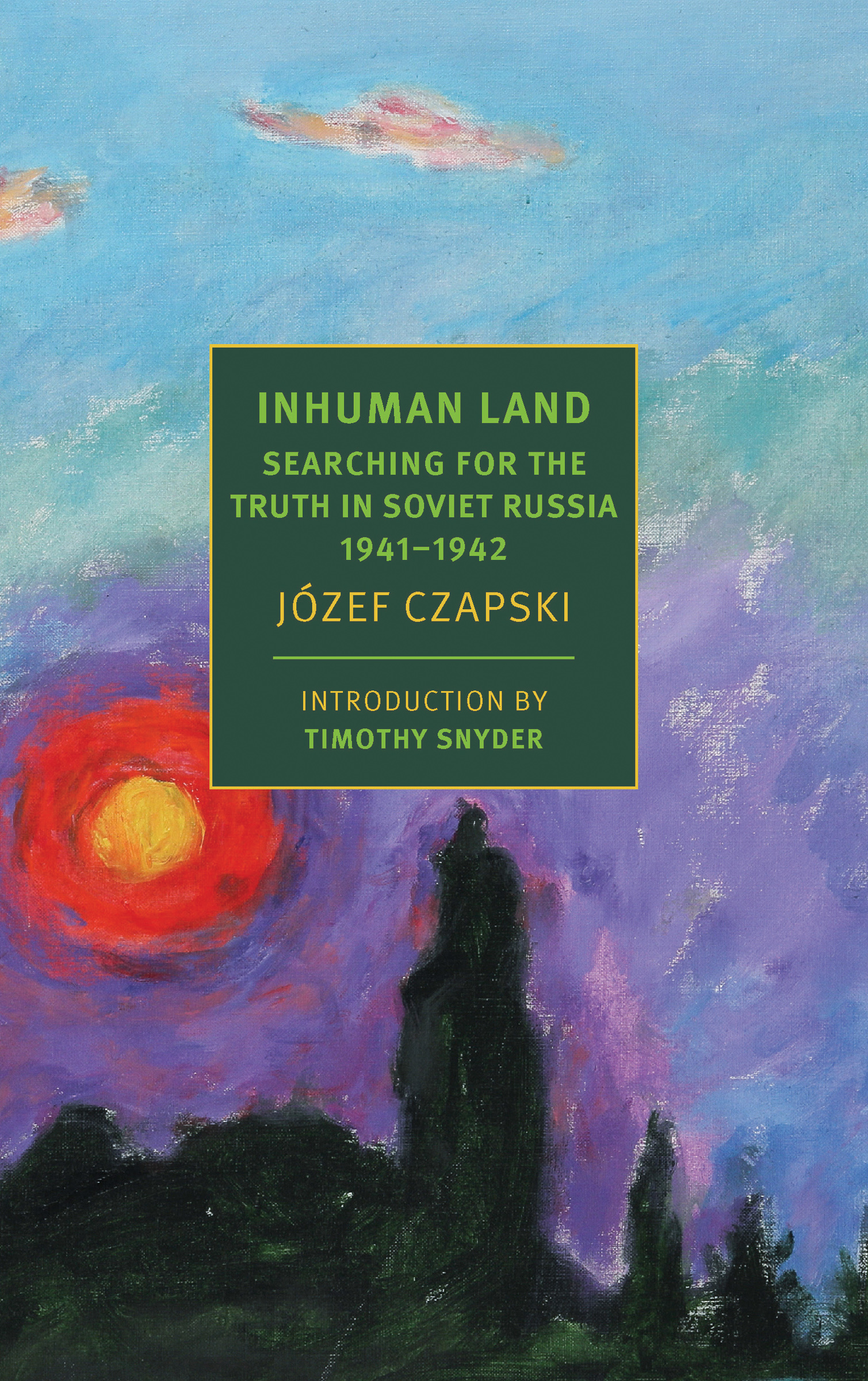

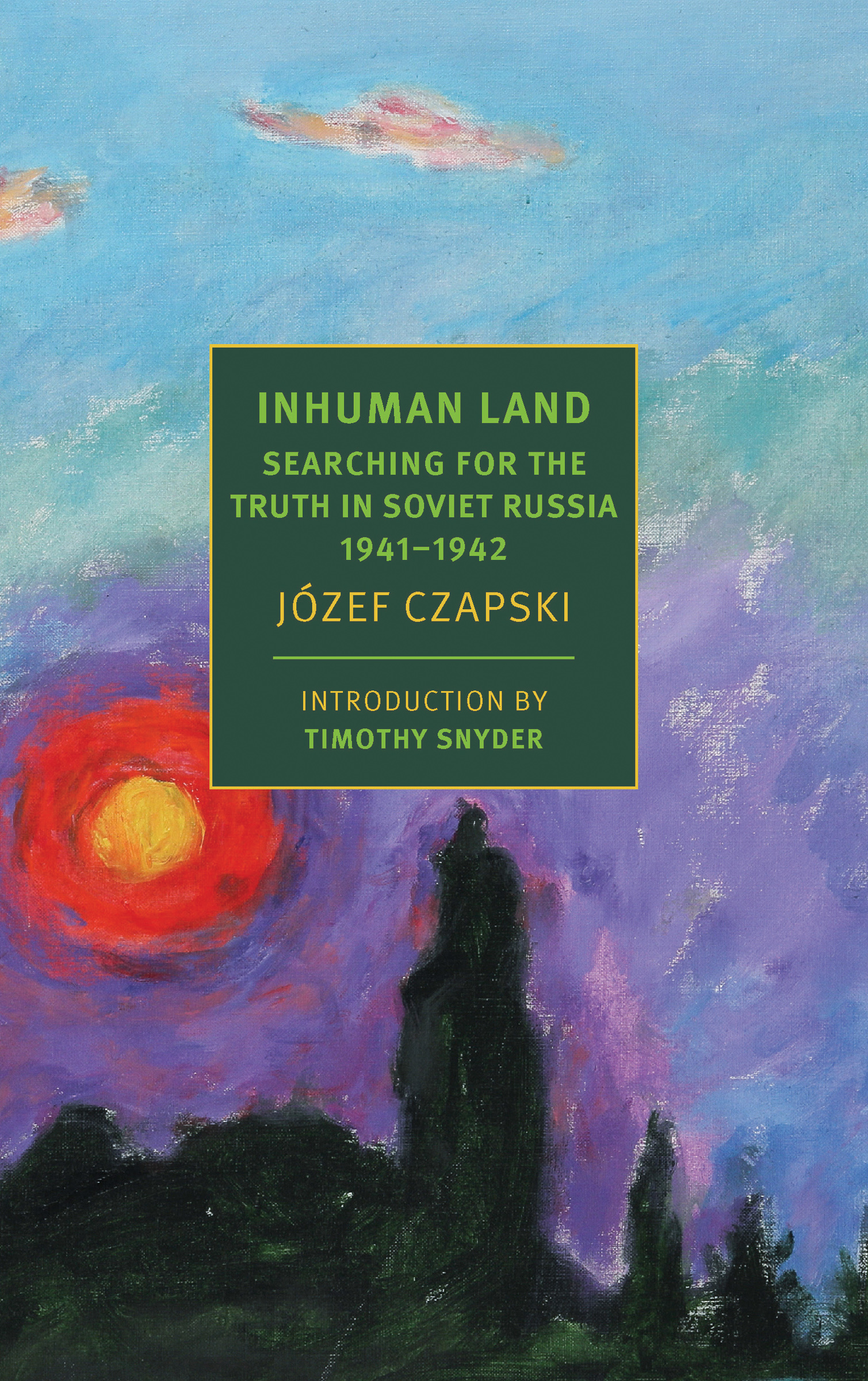

INHUMAN LAND

Searching for the Truth in Soviet Russia 19411942

JZEF CZAPSKI

Translated from the Polish by

ANTONIA LLOYD-JONES

Introduction by

TIMOTHY SNYDER

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Part one copyright 2001 by Wydawnictwo Znak, Krakw

Part two copyright by Weronika Orkisz

Translation copyright 2018 by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Introduction copyright 2018 by Timothy Snyder

All rights reserved.

Originally published in the Polish language as Na nieludzkiej ziemi

This translation is published by arrangement with Spoeczny Instytut Wydawniczy ZNAK

Sp. z o.o., Krakw, Poland

All the illustrations are used here by kind permission of the National Museum in Krakw (Jzef Czapski Archive at the Princes Czartoryski Library), apart from: page 370, by kind permission of the National Digital Archive (from the Tadeusz Szumaski Photographic Archive), and page 444, CPA agency collection, by kind permission of Stanisaw Mancewicz.

Cover image: Jzef Czapski, Le Loiret, 1976; Jzef Czapski; collection of Richard and Barbara Aeschlimann, Chexbres; photograph by Alain Herzog

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Czapski, Jzef, 18961993, author. | Lloyd-Jones, Antonia, translator.

Title: Inhuman land : Searching for the Truth in Soviet Russia, 19411942 / by Jzef Czapski ; translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones.

Other titles: Na nieludzkiej ziemi. English

Description: New York : New York Review Books, [2018] | Series: New York Review Books classics | Translation of: Na nieludzkiej ziemi. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018024072 (print) | LCCN 2018040660 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681372570 (epub) | ISBN 9781681372563 | ISBN 9781681372563 (alk. paper) Subjects:

LCSH: Czapski, Jzef, 18961993. | World War, 19391945Prisoners and prisons, Russian. | World War, 19391945Personal narratives, Polish. | Prisoners of warPolandBiography. | Prisoners of warSoviet UnionBiography. | LCGFT: Autobiographies.

Classification: LCC D805.R9 (ebook) | LCC D805.R9 C8513 2018 (print) | DDC 940.54/7247092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018024072

ISBN 978-1-68137-257-0

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

J ZEF Czapski was a gifted child of a fading European aristocracy, a lifelong admirer of Russian thought, and perhaps the greatest Polish painter of the twentieth centurythough during most of it he lived in obscurity in France. He was an introvert with the skills of an extrovert, able to speak to almost anyone about almost anything, who wanted only to compose his landscapes, portraits, and still lifes in peace. Inhuman Land, his recollection of the Second World War, is the work of a person who faced impossible demands with grace. One evening in Paris, decades after the events recounted in this book, Czapski attended a dinner party. When, unusually for him, he began to tell stories from the war, a French scholar gaped: I had no idea what life could be!

That evening, the Frenchman listened. One must attend closely to Czapski. He was very humble. His style is descriptive rather than declarative, and he draws no conclusions. He gives voice to people and vitality to situations, which means that he withdraws himself. In this memoir, he tells us almost nothing about his life as an artist in interwar Paris and Warsaw, and very little about his confinement in Soviet concentration camps at the beginning of the Second World War.

Czapski was settling down in the late 1930s, with an atelier in Warsaw and a room near his friend Ludwik Hering in the suburbs. Just when it seemed he had found his way into life, he was summoned to war.

When Nazi Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Czapski, then forty-three, was mobilized as a reserve officer of the Polish Army. The Soviet Union invaded Poland on September 17, falling upon retreating Polish forces from the rear. Czapski was captured by the Red Army near the village of Chmielek and sent to a camp in a former cloister in Starobilsk, in what is now the Luhansk region of eastern Ukraine. About six months later, in April 1940, Czapski and a few of his fellow prisoners from Starobilsk were transferred to a camp at Gryazovets, about five hundred kilometers north of Moscow, where they met other Polish officers coming from camps at Kozelsk and Ostashkov.