JZEF CZAPSKI (18961993), a painter and writer, and an eyewitness to the turbulent history of the twentieth century, was born into an aristocratic family in Prague and grew up in Poland under czarist domination. After receiving his baccalaureate in Saint Petersburg, he went on to study law at Imperial University and was present during the February Revolution of 1917. Briefly a cavalry officer in World War I, and decorated for bravery in the PolishSoviet War, Czapski went on to attend the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakw and then moved to Paris to paint. He spent seven years in Paris, moving in social circles that included friends of Proust and Bonnard, and it was only in 1931 that he returned to Warsaw and began exhibiting his work and writing art criticism. When Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, Czapski sought active duty as a reserve officer. Captured by the Germans, he was handed over to the Soviets as a prisoner of war, though for reasons that remain mysterious he was not among the twenty-two thousand Polish officers who were summarily executed by the Soviet secret police. Unwilling to live in postwar Communist Poland, Czapski set up a studio outside of Paris. His essays appeared in Kultura, the leading intellectual journal of the Polish emigration that he helped establish; his painting underwent a great final flowering in the 1980s. Czapski died, nearly blind, at ninety-six.

ALISSA VALLES is the author of the poetry collection Hospitium. Her translations include Zbigniew Herberts Collected Poems and Collected Prose and Ryszard Krynickis Our Life Grows (NYRB Poets).

IRENA GRUDZISKA GROSS s books include Czesaw Miosz and Joseph Brodsky: Fellowship of Poets and The Scar of Revolution: Tocqueville, Custine, and the Romantic Imagination. She is a 2018 Guggenheim Foundation Fellow and lives in Brooklyn, New York.

OTHER BOOKS BY AND ABOUT JZEF CZAPSKI PUBLISHED BY NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

BY JZEF CZAPSKI

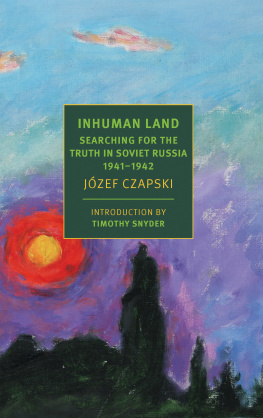

Inhuman Land: Searching for the Truth in Soviet Russia, 19411942

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Introduction by Timothy Snyder

Lost Time: Lectures on Proust in a Soviet Prison Camp

Translated by Eric Karpeles

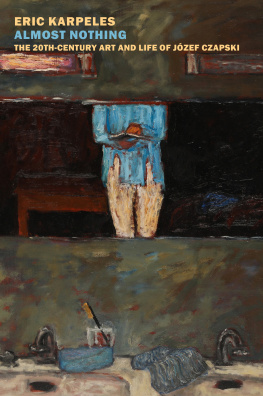

BY ERIC KARPELES

Almost Nothing: The 20th-Century Art and Life of Jzef Czapski

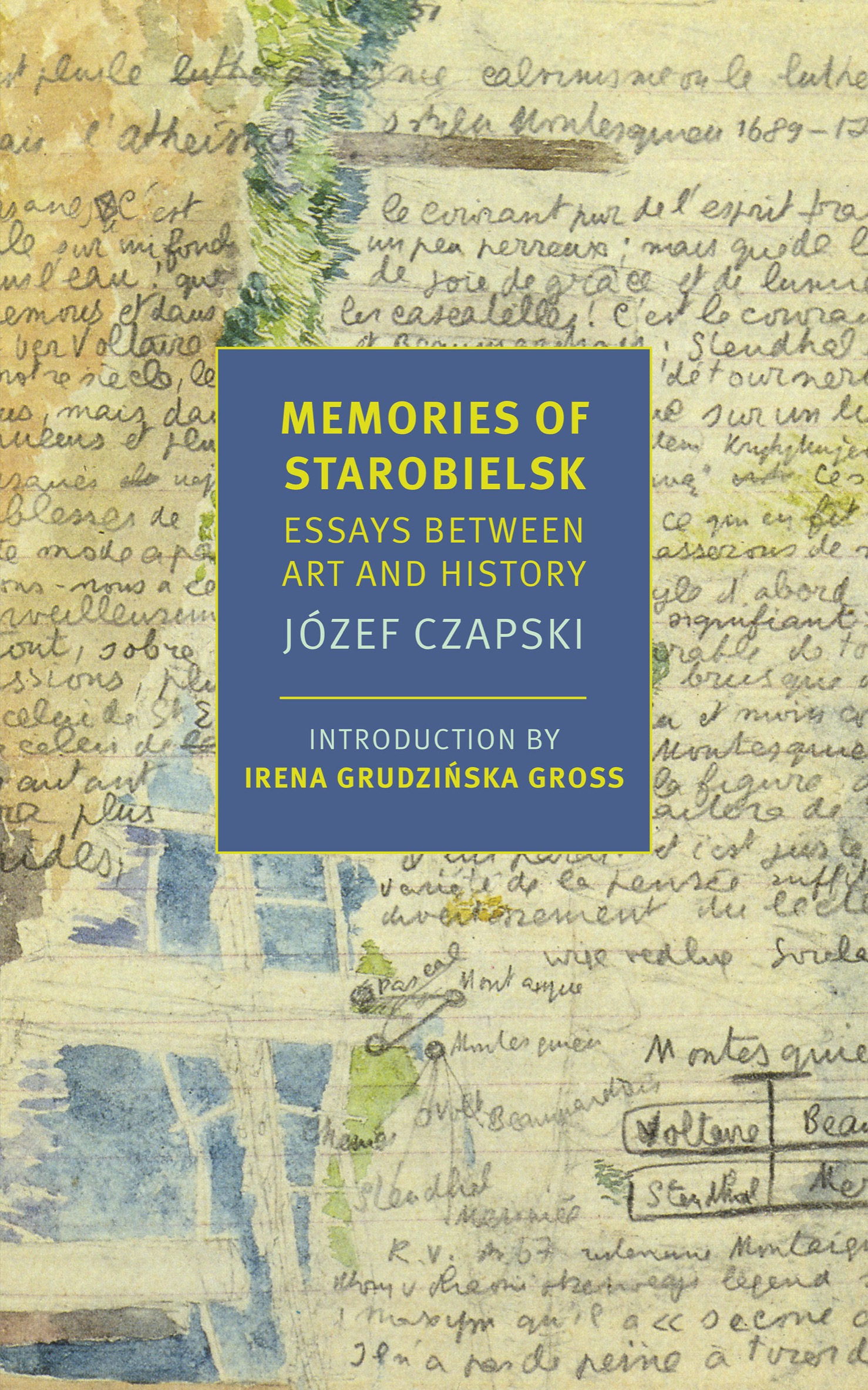

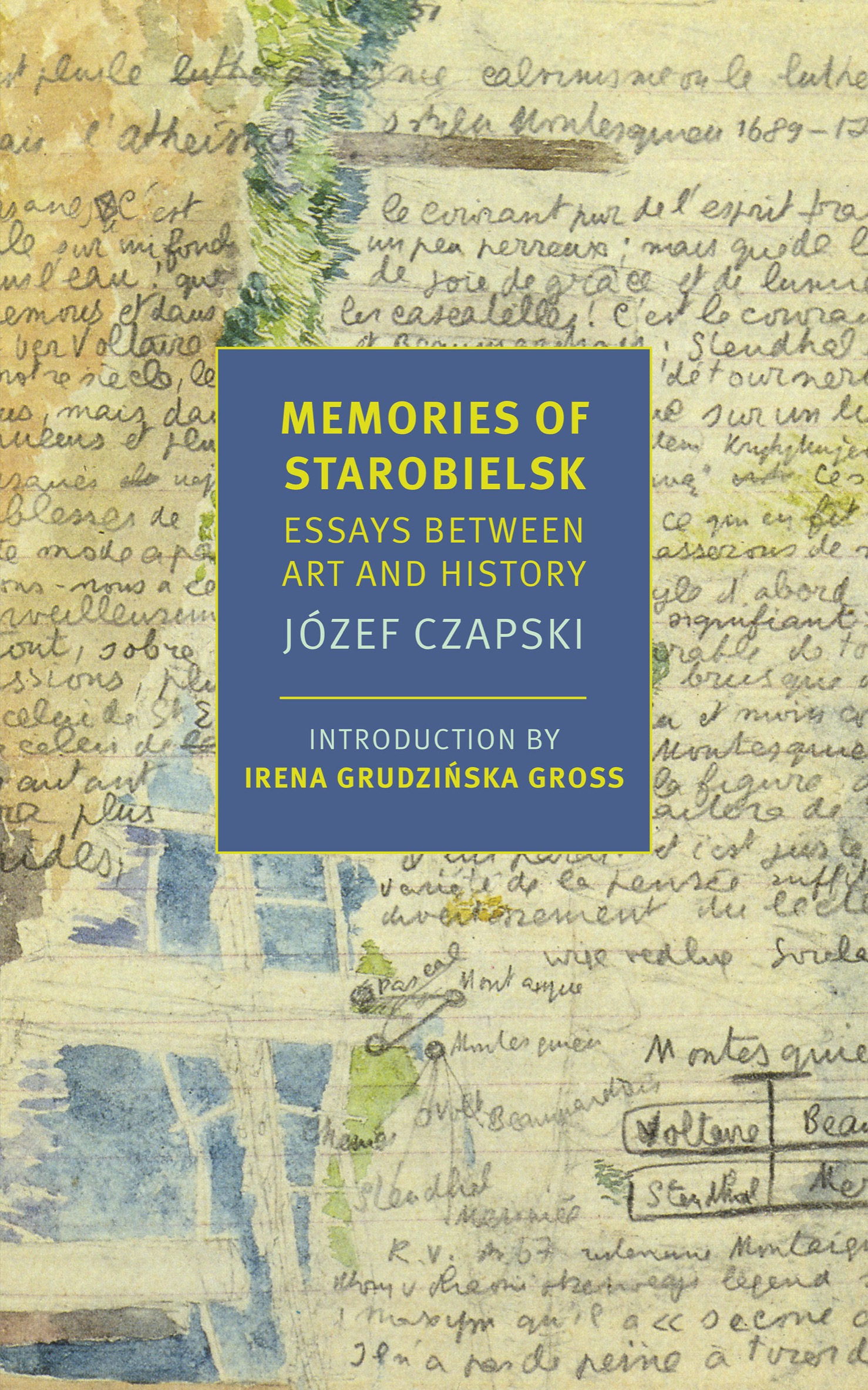

MEMORIES OF STAROBIELSK

Essays Between Art and History

JZEF CZAPSKI

Edited and translated from the Polish by

ALISSA VALLES

Introduction by

IRENA GRUDZISKA GROSS

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Copyright 2022 by NYREV, Inc.

Essays copyright by the Estate of Jzef Czapski

Translation copyright 2022 by Alissa Valles

Introduction copyright 2022 by Irena Grudziska Gross

All rights reserved.

Memories of Starobielsk, published as Souvenirs de Starobielsk, copyright 1987 by ditions Noir sur Blanc, France; other essays published by arrangement with Spoeczny Instytut Wydawniczy Znak Sp. z o.o., Krakw, Poland.

This publication has been supported by the POLAND Translation Program.

Cover image: A page from Jzef Czapskis journal, showing a watercolor sketch of Starobielsk

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Czapski, Jzef, 18961993, author. | Grudziska Gross, Irena, writer of introduction. | Valles, Alissa, translator.

Title: Memories of Starobielsk: Essays Between Art and History / Jzef Czapski; introduction by Irena Grudziska Gross; translated by Alissa Valles.

Description: New York: New York Review Books, [2022] | Series: New York Review Books classics

Identifiers: LCCN 2020016062 (print) | LCCN 2020016063 (ebook) | ISBN 9781681374864 (paperback) | ISBN 9781681374871 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Czapski, Jzef, 18961993. | Starobilsk (Ukraine: Concentration camp) | Arts.

Classification: LCC N7255.P63 C93 2022 (print) | LCC N7255.P63 (ebook) | DDC 700.9dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016062

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020016063

ISBN 978-1-68137-487-1

v1.0

For a complete list of titles, visit www.nyrb.com

INTRODUCTION

Memories of Russia

T he first thing people noticed about Jzef Czapski was his height. Like many of the men (and some of the women) in his family, he was very tall. He was also thin and somewhat awkward. His friend Wojciech Karpiski called him a smiling Don Quixote. His biographer Eric Karpeles has compared him to an elongated, striding man by Giacometti, capturing not only his tallness but also his shy way of moving in company, among people for the most part much shorter than he was. Mary McCarthy made a similar observation. Describing, in a letter to Hannah Arendt, her visit to a packed show of Vermeer, she writes that the only person enjoying it was a Polish painter I know called Czapski... he is an old man, six and a half feet tall, and he was moving contentedly through the crowd like an ostrich, taking pictorial notes in a sketchbook.

Czapski towered over everybody, and yet Polish friends and acquaintances referred to him by a diminutive: Jzio. There was something childlike about him, an enthusiasm, an openness, curiosity, and liveliness, a quickness of thought and feeling. Worn down by war and exile, Czapski grew old earlyin letters to Ludwik Hering, probably the love of his life, written in 1947, when he was only fifty-one, he is already complaining about getting oldand living as he did almost to the end of the twentieth century, he was old for a long time. Still, he was always Jzio.

Jzef Czapski was born in 1896 in Prague, in a Thun palace that belonged to his mothers family, and grew up in Belorussia, then part of the Russian Empire. He came from an aristocratic family, and many of his Baltic-German, Austrian, and Polish ancestors and elders, for whom nationalism was a form of parochialism, were in the service of the Russian or Austrian Empires. Czapskis father was so indifferent to his Polish background that he learned Polish only as an adult. His mother, however, though Austrian, felt a deep affection for the suffering people of Poland, divided as their country had been between Russia, Austria, and Prussia since the eighteenth century, and she passed that love on to her children. For all that, it was to Russia that Czapski was sent for his education, attending gymnasium, military academy, and law school in Saint Petersburg.

The main dates of Czapskis life rhyme with the historical events that shook Europe throughout the last century. He was in Saint Petersburg at the start of the First World War, when the city was renamed Petrograd, and also for the February Revolution of 1917. Returning to Poland, he enlisted in the Polish army, though his pacifist convictions led him to withdraw from it almost right away, a decision he was to regret and reverse a year later. He fought in the PolishSoviet War of 19191921, and he was sent on a mission to Petrograd to find five missing Polish military men, a mission that was unsuccessful because the men had already been killed by their Russian captors. In the 1920s he studied painting in Krakw and Paris before returning to Warsaw. When Germany attacked Poland in September 1939, Czapski, as a reserve officer, was mobilized immediately and taken prisoner twenty-seven days later. He was one of some fifteen thousand Polish prisoners the Germans turned over to the Soviets, with whom they were allied at that point. The prisoners were then transported into the Soviet Union and placed in camps at Starobielsk, Kozielsk, and Ostashkov, most of them to be secretly executed by the Soviet military police between April and May 1940. Czapski was in a group of four thousand Polish officers who were held at Starobielsk. Thanks to inquiries made by his sister and his influential Austrian and German relatives, he was moved to another camp and survived. Out of almost four thousand officers, only seventy-nine survived. I am one of them, Czapski wrote in his