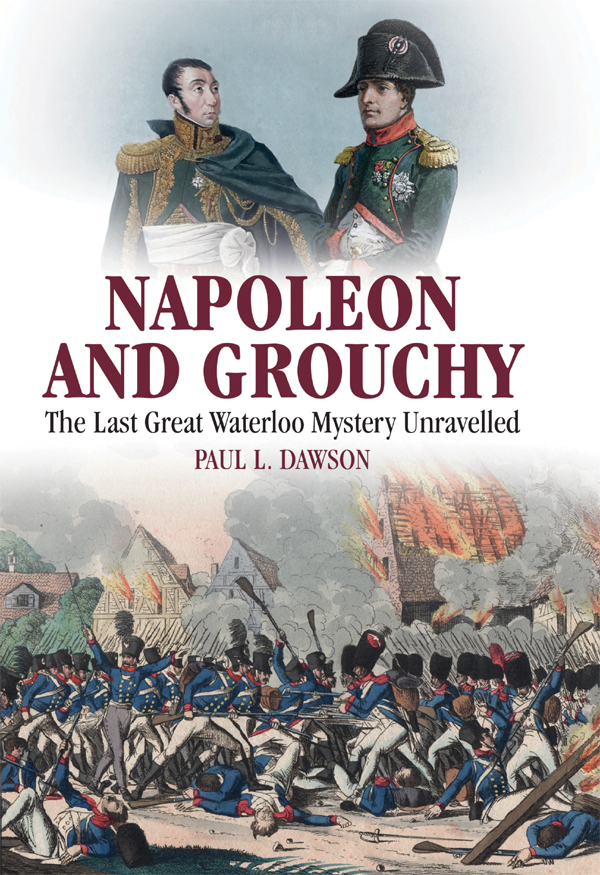

NAPOLEON AND GROUCHY

The Last Great Waterloo Mystery Unravelled

NAPOLEON AND GROUCHY

The Last Great Waterloo Mystery Unravelled

Paul L Dawson

NAPOLEON AND GROUCHY

The Last Great Waterloo Mystery Unravelled

This edition published in 2017 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright Paul L Dawson

The right of Paul L Dawson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-52670-067-4

eISBN: 978-1-52670-069-8

Mobi ISBN: 978-1-52670-068-1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please visit

www.frontline-books.com

email

or write to us at the above address.

Acknowledgements

I n the preparation of this book I would like to thank all those who have offered advice and support, all those who have helped me with my research. I am indebted to Mr John Franklin for his guidance, advice and provision of some research materials. Furthermore, I must also thank M. Yves Martin, Mr Ian J. Smith, John Lubomski and Sally Fairweather for their generous assistance with, and photographing of, archival material at the Archives Nationales and Service Historique de la Dfence Arme du Trre, in Paris.

I must single out Ian Smith for his friendship, dedicated support to the project and excellent company during our numerous research trips to Paris. His advice and guidance during our many thousands of hours of conversation over numerous bottles of red wine was, and is, of immense help in understanding the wealth of data that we have gathered, to synthesise it into a cohesive narrative. Without this most generous support by Ian the book would have taken far longer to complete.

Erwin Muilwijk deserves a special word of praise, without his assistance in the provision of Dutch - Belgian source material this book could never have come to fruition. Lieutenant-Colonel Timmermans must be thanked for illustrations. I heartily encourage visitors to his excellent website http://Napolon-monuments.eu/. Sally Fairweather must be thanked for proof reading this text.

Notes on the Sources

T his study is based on two forms of evidence: personal testimony written after the events took place and empirical hard data in the form of orders and letters written on 17 and 18 June, as well as regimental muster lists. The material used has undergone a variety of processes before it was read by the author. Not all the archival paperwork prepared in 1815 has survived to the current day. Not all written memoirs of participants have survived. Those cited here are just those the author could identifymany more may exist in private collections, museums and libraries, and they may well tell a different narrative from that presented here. The narrative has been constructed from the sources available to the author.

In creating our narrative, we have endeavoured to let the primary sources speak for themselves without having to fit what they say into a superficial construct created by other authors. We must be aware, however, of the limitations and failings of these memoirs as a source of empirical data. The memoir, as Paul Fussell has established, occupies a place between fiction and autobiography.

Since Fussells work, recent research and developments in the fields of clinical and behavioural psychology, memory and the response to stress has called into question the value of memoirs and so-called eyewitness reports written by participants. Neuroscientist John Coates conducted research into memory; his study undertaken between 2004 and 2012 found that what is recalled from memory is what the mind believes happened rather than what actually happened. This effect is often referred to as false memory. A memoir, letter or other material used to help create a narrative of events is of limited value in terms of historical interpretation without context. This is defined as hermeneutics. Hermeneutics addresses the relationship between the interpreter and the interpreted; viz: What does it mean? What were the authors intentions? Is the source authentic?

Therefore, the historians primary aim is decoding the language of the source used, to understand the ideological intentions of the author, and to locate it within the general cultural context to which the source material belongs. This is the reason why the police take statements immediately from as many eyewitnesses as possible without allowing the eyewitnesses to hear what others are saying. They then tease out the facts from this jumble of data.

Consulting the various archive boxes at the Service Historique de la Dfence Arme du Trre at Vincennes in Paris quickly reveals that a lot of accepted fact on the battle cannot be verified. Marshal Grouchy, whose later life was obsessed with presenting his side of Waterloo, printed a vast amount of information in the 1840s, particularly orders, reports from field officers, marching orders, comments, etc. in order to verify his version of events. We do not know if the material produced by Grouchy is a word-for-word transcript, or if it has been edited, or if he published all the material he had. Grouchy, in order to corroborate his version of events, published the order book of Marshal Soult, the major-general of the Arme du Nord. The book exists in three forms: a) a hand written copy made by Grouchy housed in Archives Nationales de France; b) the published manuscript; and c) the du Casse copy made in 1865. The original is missing, so we cannot be sure that Grouchys handwritten version is an exact copy. In order to strengthen his argument, he obtained and copied, but never published, Vandammes correspondence register from 1815; the original document being lost. Grouchy also published his own, now lost, register of correspondence from 1815. Vandammes correspondence and Grouchys data tallies with the order book of Soulta coincidence brought about by Grouchy, or are all three books in accord because they contain the same material generated on those fateful days in 1815? I believe all three books are word-for-word copies of the lost originals. Soult and Vandamme were still alive when Grouchy made his copies, and both men would have made comment. Vandamme did make comment on the 1815 campaign, not against Grouchy, but in support of him. Clearly if Vandamme felt he had lied, he would have made it obvious.

Into this mix comes the work of Albert du Casse. Pierre-Emmanuel-Albert, Baron du Casse (also Ducasse, 16 November 1813-14 March 1893), was a French soldier and military historian born at Bourges on 16 November 1813. He is best known for being the first editor of the correspondence of Napolon I. He often published as Albert du Casse.

In 1849 he became aide-de-camp to Prince Jrme Bonaparte, ex-King of Westphalia, then governor of the Invalides, on whose commission he wrote Mmoires pour servir a lhistoire de la campagne de 1812 en Russie (1852). Subsequently, he published Mmoires du roi Joseph (1853-1855), and, as a sequel, Histoire des ngotiations diplomatiques relatives aux traits de Morfontaine, de Lunville et dAmiens , together with the unpublished correspondence of the Emperor Napolon I with Cardinal Fesch (1855-1856). From papers in the possession of the imperial family he compiled Mmoires du prince Eugene (1858-1860) and Rfutation des Mmoires du duc de Raguse (1857), part of which was inserted by authority at the end of volume six of the Mmoires .

Next page