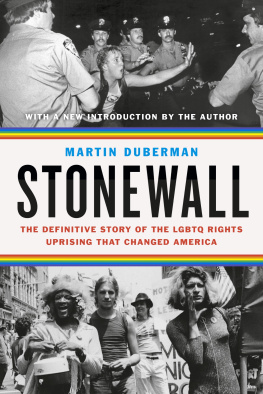

Stonewall

Martin Duberman

AGAIN AND ALWAYSFOR ELI

Becoming human is becoming individual, and we become individual under the guidance of cultural patterns which give form, order, point, and direction to our lives. [But] we must descend into detail, past the misleading tags, past the metaphysical types, past the empty similarities, to grasp firmly the essential character of not only the various cultures but the various sorts of individuals within each culture, if we wish to encounter humanity face to face.

CLIFFORD GEERTZ

The Interpretation of Culture

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M y greatest debt is to the six people who trusted me to tell their stories and endured the multiple taping sessions needed to make that possible: Yvonne (Maua) Flowers, Jim Fouratt, Foster Gunnison, Jr., Karla Jay, Sylvia Ray Rivera, and Craig Rodwell. I sent the completed manuscript to all six to check for factual inaccuracies, and listened carefully to their occasional disagreement with this or that emphasisbut all understood that finally I could not surrender to them the authorial responsibility to interpret the evidence. Unless otherwise noted (which happens with some frequency), all the quotations in this book are from the transcripts of those taped interviews with my six subjects, together totaling several hundred hours; Im alerting the reader here to the source of most of the quotations in order to avoid having to make repetitive citations throughout the book itself.

I have also been fortunate in being allowed to use several major archival collections still in private hands. In this regard, I am especially indebted to Foster Gunnison, Jr., and William B. Kelley. My ability to tell the story of the pre-Stonewall political movement in some detail has largely hinged on having access to those two extraordinary collections. In addition, the rich International Gay Information Center (IGIC) Papersformerly known as the Hammond-Eves Collectionin the New York Public Library Manuscript Division has recently been processed and contains invaluable records and correspondence.

All of this material has proven to be so fresh and informative that I have paused at certain points in the book to convey it. But not, I hope, paused too long; wherever I felt the documentary details threatened to overwhelm the narrative and convert the book into a traditional monograph, I have relegated them to the (sometimes lengthy) footnoteswhich I have in turn relegated to the back of the book.

I am grateful to a number of people (other than the six subjects themselves) who allowed me to tape-record their recollections and thereby flesh out a number of critical points in the narrative: Martin Boyce, Nick Browne, Ryder Fitzgerald, Robert Heide, Robert Kohler, Sascha L., Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, Chuck Shaheen, Jim Slaven, Gregory Terry, Joe Tish, and Ivan Valentin. I am also indebted to Steven Watson for providing me with tapes and transcripts of interviews he did in the late seventies with Marsha P. Johnson, Minette, Sylvia Ray Rivera, and Holly Woodlawn.

For assorted other favors, source materials, encouragement and leads, Im grateful to Mariette Pathy Allen, Desmond Bishop, Mimi Bowling, Rene Cafiero, Barry Davidson, Richard Dworkin, Dan Evans, Barbara Gittings, Eric Gordon, Erica Gottfried, Liddell Jackson, Marty Jezer, Kay Tobin Lahusen, Tom McGovern, Joan Nestle, Duncan Osborne, Jim Owles, Gabriel Rotello, Vito Russo, Bebe Scarpi, Bree Scott-Hartland, La Vaughan Slaven, Mark Thompson, Jack Topchik, Jeffrey Van Dyke, Paul Varnell, Bruni Vega, Rich Wandel, Fred Wasserman, Thomas Waugh, and Randy Wicker. For the Stonewall chapter, I am indebted to Dolly and Leo Scherker for permission to consult materials that their son, Michael, had gathered for a planned oral history of the Stonewall riots that was tragically aborted by his premature death. I have included only a few brief remarks from Scherkers interviews (so cited in each instance in the accompanying footnote), but hearing in full his twenty or so tapes has broadly informed my own work.

Finally, my manuscript has greatly benefited from the careful readings Jolanta Benal, Matthew Carnicelli, John DEmilio, Frances Goldin, Arnie Kantrowitz, William B. Kelley, and Eli Zal gave it; their cogent responses caused me to rethink any number of sections in the narrative. The pioneer activist Jim Kepnerwhose encyclopedic knowledge of the gay movement is unrivaledprovided me with a detailed, incisive commentary that saved me from error and deepened my understanding at many points. I have also been extremely fortunate to have had Arnold Dolin of NAL/Dutton as the books editor and Frances Goldin as its agent. Both have guided Stonewall through its various incarnations with the dedication and skill for which they are already well known.

Finally, to my partner, Eli Zalto whom this book is dedicatedI owe the priceless gift of sustained, loving support.

PREFACE

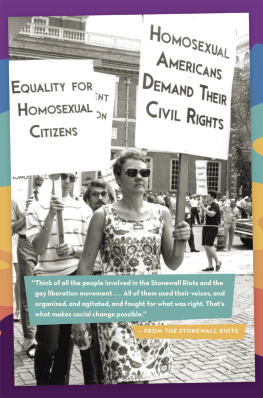

S tonewall is the emblematic event in modern lesbian and gay history. The site of a series of riots in late June-early July 1969 that resulted from a police raid on a Greenwich Village gay bar, Stonewall has become synonymous over the years with gay resistance to oppression. Today, the word resonates with images of insurgency and self-realization and occupies a central place in the iconography of lesbian and gay awareness. The 1969 riots are now generally taken to mark the birth of the modern gay and lesbian political movementthat moment in time when gays and lesbians recognized all at once their mistreatment and their solidarity. As such, Stonewall has become an empowering symbol of global proportions.

Yet remarkablysince 1994 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Stonewall riotsthe actual story of the upheaval has never been told completely, or been well understood. We have, since 1969, been trading the same few tales about the riots from the same few accountstrading them for so long that they have transmogrified into simplistic myth. The decades preceding Stonewall, moreover, continue to be.regarded by most gays and lesbians as some vast neolithic wastelandand this, despite the efforts of pioneering historians like Allan Brub, John DEmilio and Lillian Faderman to fill in the landscape of those years with vivid, politically astute personalities.

The time is overdue for grounding the symbolic Stonewall in empirical reality and placing the events of 1969 in historical context. In attempting to do this, I felt it was important not to homogenize experience to the point where individual voices are lost sight of. My intention was to embrace precisely what most contemporary historians have discarded: the ancient, essential enterprise of telling human stories. Too often, in my view, professional historians have yielded to a sociologizing tendency that reduces three-dimensional lives to statistical cardboardand then further distances the reader with a specialized jargon that claims to provide greater cognitive precision but serves more often to seal off and silence familiar human sounds.

I have therefore adopted an unconventional narrative strategy in the opening sections of this book: the recreation of half a dozen lives with a particularity that conforms to no interpretative category but only to their own idiosyncratic rhythms. To focus on particular stories does not foreclose speculation about patterns of behavior but does, I believe, help to ensure that the speculation will reflect the actual disparities of individual experience. My belief in the irreducible specialness of each life combines with a paradoxical belief in the possibility that lives, however special, can be shared. It is, if you like, a belief in democracy: the-importance of the individual, the commonality of life.