Marcel Duchamp

Titles in the series Critical Lives present the work of leading cultural figures of the modern period. Each book explores the life of the artist, writer, philosopher or architect in question and relates it to their major works.

In the same series

Michel Foucault

David Macey

Jean Genet

Stephen Barber

Pablo Picasso

Mary Ann Caws

Franz Kafka

Sander L. Gilman

Guy Debord

Andy Merrifield

Marcel Duchamp

Caroline Cros

Translated by Vivian Rehberg

REAKTION BOOKS

Published by Reaktion Books Ltd

33 Great Sutton Street,

London EC1V 0DX, UK

www.reaktionbooks.co.uk

First published 2006

Copyright Caroline Cros 2006

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers.

Page references in the Photo Acknowledgements and

Index match the printed edition of this book.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Biddles Ltd, Kings Lynn

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Cros, Caroline

Marcel Duchamp (Critical lives)

1. Duchamp, Marcel, 1887-1968 2. Artists - France - Biography

I. Title

709.2

eISBN: 9781780232393

Contents

Ed Paschke, my professor at the School of the Art Institute in Chicago, introduced me to the Readymade and to Marcel Duchamps ideas. He had a great influence on me. He taught me to use my environment. Everything is already there. It is up to the artist to reorganize things, to put them together like a new chemical compound.

Jeff Koons, in Le Monde, 31 August 2005

We are now, in 2005, at a moment of aesthetic pause and reflection that is masked by activity and gallery growth patterns alongside the appearance and disappearance of artists in a constant flow of representation. In some ways this could be the perfect environment to play in. A situation encouraged by the so-called dynamic art market that always works to suppress the potential of sitting still in relation to what happens to be renegotiating itself in front of you. It is impossible to talk about the influence of Duchamp at the moment within the ongoing activated art world. Such an influence is hidden and veiled, but the ideas floating around make the potential of an obligation to de-code/re-code imminent and sloppy at the same time. We are in a moment of stasis and cultural battle simultaneously.

Liam Gillick, 2005

1

Introduction

When the Duchamp family of exceptional artists were living together in the Normandy countryside, the older brothers played chess, their parents and their visiting friends played cards, two of the daughters and Madame Duchamp played music, and the two middle children, Suzanne and Marcel, teased each other affectionately, sharing the secrets that would seal their bond. It was during his childhood that Duchamp developed his taste for chess and games involving hazard and chance. Games, then, in Jacques Villons yard in Puteaux, became a subject for portraits painted during his teens (The Chess Game, 1910; Philadelphia Museum of Art), and when Duchamp liberated himself from the family circle during his American exile several years later, chess became his passion. Throughout his life he played on a daily basis, like a painter heading to work in the studio alone, every day.

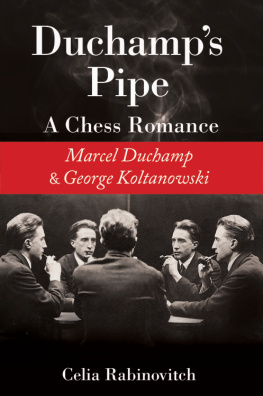

Duchamp admitted it straight away: he much preferred playing chess with professionals, whom he considered the real artists, than keeping company in the art world and acting the part of the painter or cinematographer. Even before he became a professional chess player himself, he encountered other chess fanatics, besides his brothers, like Walter Arensberg and Man Ray.

During his stay in Buenos Aires in 1919, where he joined a local chess club, he acquired his professional know-how by cutting out games from the newspaper and mastering the system developed by the extremely popular Cuban chess player Jos Ral Capablanca.

When he returned to New York in 1922, his friend Henri-Pierre Roch encouraged him to continue his artistic research, but Duchamp responded quite firmly:

No, I really dont feel like broadening my horizons. When I get a little money, I will do different things. But I dont think that the few hundred francs or whatever cash I would get out of it could make up for the hassle of seeing this reproduced for the public. Ive had it up to here with becoming a painter

Indeed, less than one year later, in 1923, he spread the rumour that he had abandoned painting, leaving his major work, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even, unfinished.

From the point of this rupture on, Duchamp officially placed his artistic adventures second; they were to distract him from his daily chess games only sporadically. A member of the French Chess Federation, Duchamp participated in professional tournaments in Brussels, Monte Carlo, Chamonix, Grenoble, Nice, Hamburg and Rouen, where he was a member of the local chess circle.

In light of all this, what is the link between the artists unfailing attraction for chess and his life as a professional artist, which he almost always treated with disdain? Duchamp responded to that question himself by designing the poster for the 1925 chess championships in Nice, which he participated in, and by designing and creating chess pieces and miniature chess games. On 23 July 1944, he asked his friend Man Ray:

Did you get the pocket chess set? Im making (myself) 50 or so of them and then the American market will be exhausted. Too much labour involved to want to launch a grand-scale production and chess players dont want to pay huge prices for a pocket chess set.

At the time, the Nice championships poster was plastered all over France and sold by the newspaper LEclaireur du Soir for 100 francs! Needless to say, today it is a highly sought-after object.

In 1951 Duchamp went even further and surprised his friends and disciples by welcoming a young historian and professor from Toronto, Michel Sanouillet, who had written a doctoral dissertation on Dada, into the fold. Once Sanouillet paid a visit to Duchamps downtown New York studio and Marcel asked him to wait while he finished his chess game. The young historian, who would become Duchamps friend, agreed, but was astounded to discover that Duchamp was playing against a naked woman. He immediately grasped the audacity of Duchamps gesture and that this exceedingly Dada-esque greeting was a true demonstration of friendship and respect. In 1963 Duchamp reiterated the peformance in Pasadena on the occasion of his first retrospective exhibition. A well-known photograph shows Duchamp in deep concentration facing an entirely undressed Eve Babitz, her face hidden by her hair.

When Duchamp died in 1968, the American Chess Foundation, to which Duchamp and his wife Teeny belonged, printed an obituary in the New York Times:

The officers and Board of Trustees of the American Chess Foundation record a deep sense of loss at the passing of Marcel Duchamp. A giant in the world of art, he was also an important influence in the world of chess and was for many years an irreplaceable member of our Board of Directors. We take immeasurable pride in his association with us.

The intellectual mastery inherent to chess, the passion for play and competition, and above all the apprehension of the world through the filter of relativity, which is symbolized by the black and white squares of the chessboard, matched Duchamps frame of mind and offered him an abiding opportunity for satisfying his untiring quest for meaning. The rigour of the game, the concentration and detachment needed to face his tough opponents, all helped him to forge his trademark Duchampian temperament, which friends and historians have rightly related to alchemy, esotericism and Zen thought.