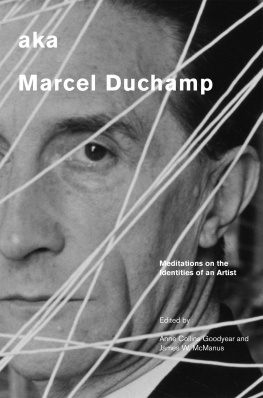

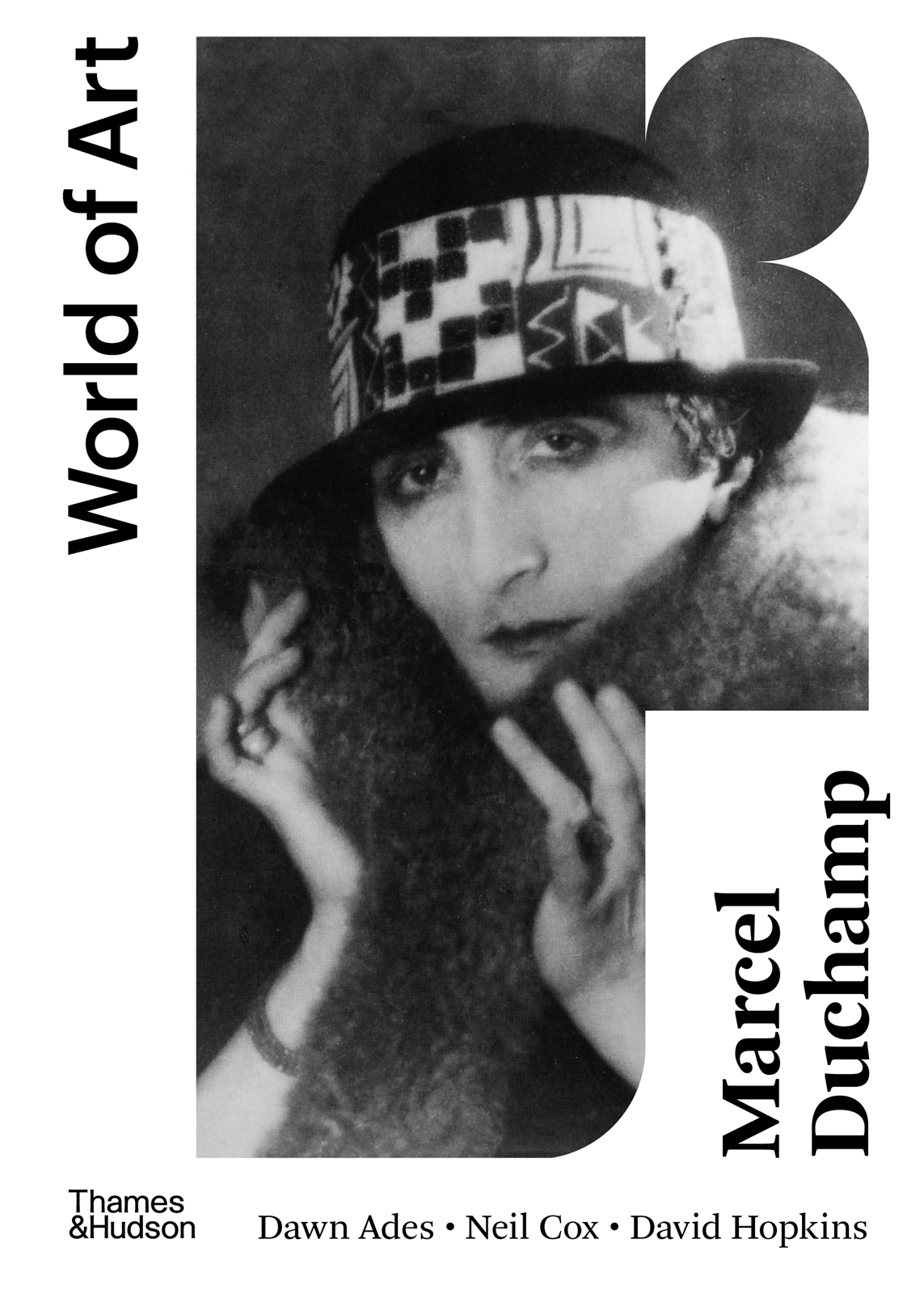

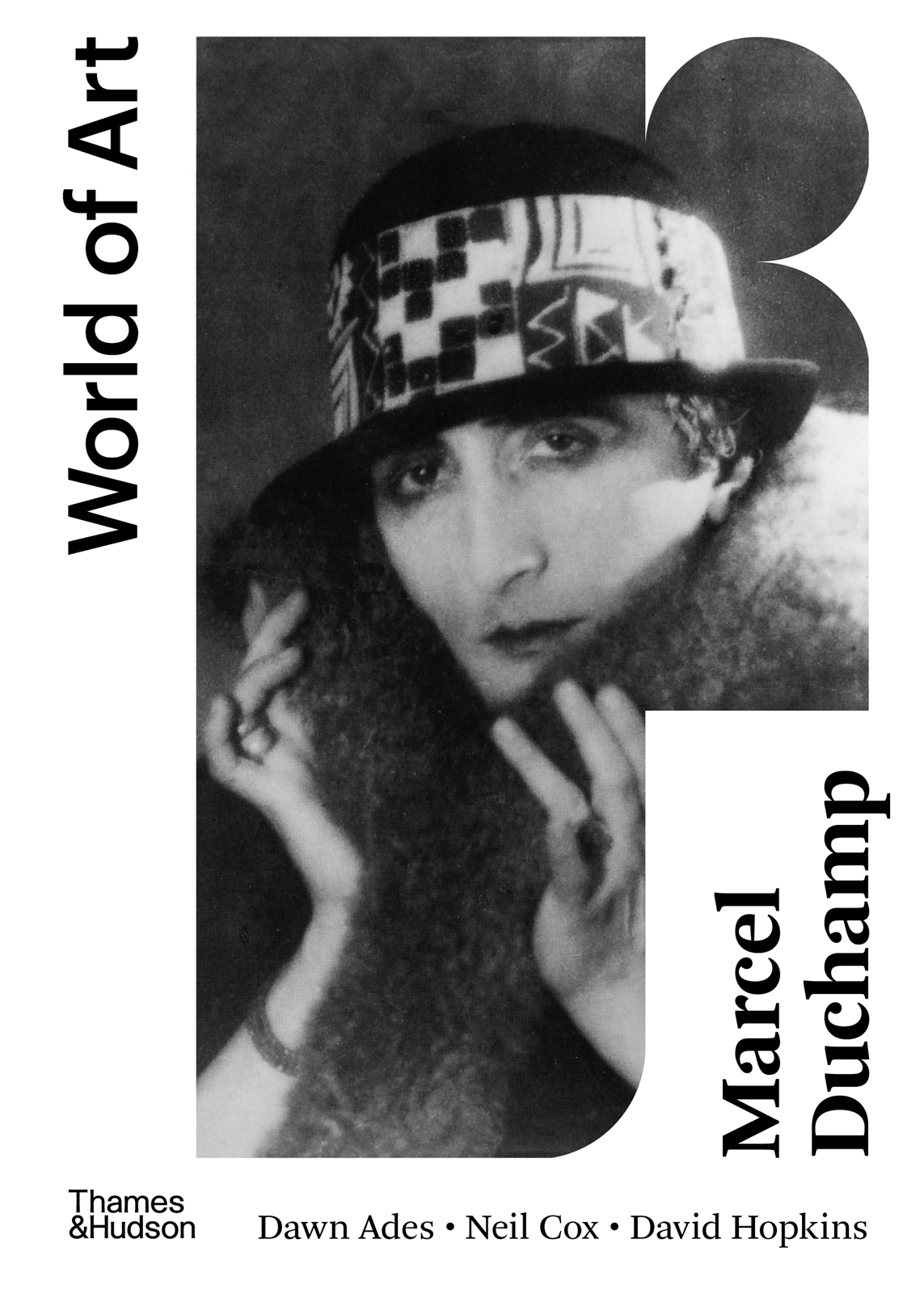

Photograph of Duchamp using a hinged mirror (detail), 1917

About the Authors

Dawn Ades is Professor Emerita of the History and Theory of Art at the University of Essex. She has written extensively on Dada, Surrealism, photography and women artists, among other things. Publications include Dada and Surrealism Reviewed (1978), Photomontage (1986), Dal (1995) and Writings on Art and Anti-Art (2015). Among the exhibitions she has organized or co-organized are Art in Latin America (1989), Fetishism: Visualizing Power and Desire (1995), Salvador Dal: The Centenary Retrospective (2004), Undercover Surrealism (2006) and Dal/Duchamp (201718).

Neil Cox is Professor of Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of Edinburgh. His books include Cubism (2000) and The Picasso Book (2010), and he has written numerous essays connecting art and philosophical ideas, including on Braque and the philosopher Martin Heidegger, and on Richard Serras drawings in relation to Hegels aesthetics. In 2011 he curated an exhibition on modern still life at the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, that included Duchamps readymades.

David Hopkins is Professor of Art History at the University of Glasgow. His books include Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst: The Bride Shared (1998), Dadas Boys: Masculinity after Duchamp (2007), Virgin Microbe: Essays on Dada (co-edited with Michael White, 2014), A Companion to Dada and Surrealism (edited, 2016), After Modern Art 19452017 (2nd edition, 2018) and Dark Toys: Surrealism and the Culture of Childhood (2021).

Acknowledgments

Without the generous assistance and considerate advice of Madame Alexina (Teeny) Duchamp and of Jacqueline Matisse, her daughter, this book could not have been written. We owe them a great debt of gratitude, and dedicate this book to the memory of Teeny, who died in 1995. We would also like to thank Tamar Francis for her invaluable help at a critical moment.

Contents

Since this book was first published in 1999, research into Duchamps work has accelerated, as the volume of publications and exhibitions featuring his work testifies. One of the most notable features of this increase in attention is the picture that has increasingly emerged of Duchamp as a meticulous technician, and of his work as complex in nature. Much, in retrospect, was overlooked or taken for granted; that the precision of his ideas was matched by precision in the materials and their manipulation and construction is becoming clear. His reputation as the father of conceptual art for a time overshadowed his tinkering as an artist. Research has rewritten the history and process of construction of some of his most famous works, including 3 Standard Stoppages (191314), and at the same time thrown up numerous unexpected questions about the development of key works and concepts, such as that of the readymade.

Yet Duchamp remains a contested figure in art history, in contemporary art criticism and in wider cultural debates, argued over by curatorial luminaries such as Boris Groys and Okwui Enwezor, and often a point of departure in philosophical essays by writers including Alain Badiou and Slavoj iek. The question of Duchamps attitudes to gender identity, or his interest in the political, have become more prominent, while his work continues to be cited as the origin point of movements or strategies such as Conceptual Art or Institutional Critique. One criticism of Duchamp historians is that they treat him as an all-knowing genius, anticipating every move in advance, thus reinstituting the authority of the artist that his work was supposed definitively to undermine. That Duchamp can be treated as the father of many aspects of a critical avant-garde attitude does seem to undermine his challenges to the idea of the artist, or of the artists relationship to the work of art, missing the dissolution of meaning that they imply. In this book, however, we examine these connections as different critical responses to Duchamp; diverse reimaginings of and struggles with Duchamps work in modern and contemporary art. Such responses themselves often play upon and interrogate Duchamps ironic resistance to artistic intention, but also trade on its essential complement: radical openness to interpretation. In art history, this has of course sometimes meant readings that seem eccentric or wilful. In keeping with openness to reinterpretation, whenever asked during his lifetime, Duchamp always acknowledged such readings positively, without ever confirming their correctness

In revising this book, we have made minor changes and additions to the text, addressing new issues in research such as Duchamps politics and his later curatorial activities, as well as correcting errors and including additional illustrations of works, some unknown or little discussed before. A new chapter, Optics and Film, has been added, and the order of the chapters revised so that the readymades are discussed earlier. The bibliography has been brought up to date, at least within the limitations of a short volume.

Critical histories still have to be written on Duchamps legacy and his precise influence on major areas of art for over three-quarters of a century, while others already published are likely to be tested and dismantled. The construction of his reputation has been in progress since before the First World War, and he has been a controversial figure ever since. The scale and longevity of the controversies around him obscure the fact that he himself in no way actively courted this notoriety. Unlike, say, Francis Picabia, Jeff Koons or Damien Hirst, to name only a few examples of artists who have used his ideas and operated on very public platforms, Duchamps own activities were often disguised or pseudonymous, and their effects have often been delayed.

Divisions of opinion about his work are different in kind from those provoked by, for instance, Picasso, with whom it is largely a matter of taste, of liking or disliking his reconstructions and representations of objects and bodies. In the case of Duchamp, it is not only the works he produced themselves that have had an effect but also his whole attitude to art, the artist and the institutions of art. He posed basic questions concerning both the definition and the survival of art in the twentieth century. Merely to question, in a Darwinian spirit, as he did, whether art is an essential and timeless phenomenon and in what new forms it might survive in the modern world has been seen by many as an act of iconoclasm or of bad faith. For others, Duchamps legacies for they should be recognized as plural have offered a sense of liberation from orthodoxies of various kinds, a salutary cleansing of accumulated aesthetic detritus and a release of art from what he considered to be the unquestioned tyranny of the eye.

A conceptual view of art has various strands and sources in Duchamps work and writings. Of most lasting impact have been the questions raised by the readymades and their offshoots, the rejection of painting as a privileged artistic activity and the withdrawal from the practice of art as a profession.

Next page