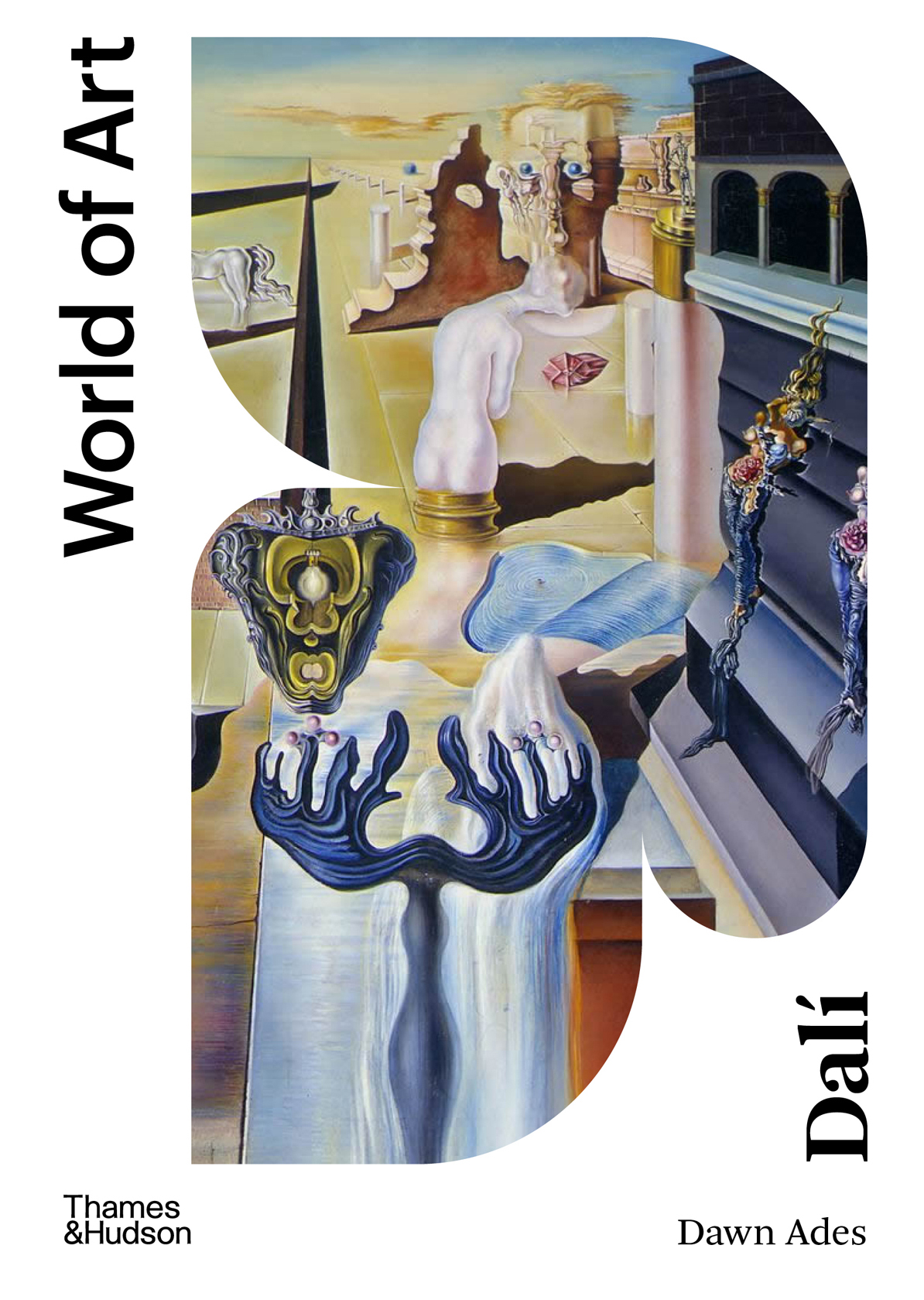

Impressions of Africa, c. 1938 (detail)

About the Author

Dawn Ades is Professor Emerita of the History and Theory of Art at the University of Essex. She has written extensively on Dada, Surrealism, photography and women artists, among other things. Publications include Dada and Surrealism Reviewed (1978), Writings on Art and Anti-Art (2015), Marcel Duchamp (with Neil Cox and David Hopkins, 2021) and Photomontage (2021). Among the exhibitions that she has organized or co-organized are Art in Latin America (1989), Fetishism: Visualizing Power and Desire (1995), Salvador Dal: The Centenary Retrospective (2004), Undercover Surrealism (2006) and Dal/Duchamp (201718).

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Professor Arthur Terry, of Essex University, for his generosity in providing material for the chapters on Dals early writing and relations with the Catalan avant-garde, and Maite Hutchinson and Monserrat Guinjoan for their help with translations from the Catalan. I would also like to thank the following for their help, encouragement, collaboration and advice, and to apologise for drawing from their work without always being able to acknowledge it: Montse Aguer, Vicen Altai, Fiona Bradley, Irene Civil, Andrew Dempsey, Patrick Elliott, Miguel Escribano, Hank Hine, Matthew Gale, William Jeffett, Frdrique Joseph-Lowery, Lewis Kachur, Elliott King, Robert Lubar, David Lomas, Ricard Mas, Jacqueline Monnier, Carme Ruiz, Toms Sharman, Charles Stuckey, Michael Taylor, Peter Tush, Eric Zafran.

Contents

Chapter 1

Early Years

Chapter 2

Dal and Lorca

Chapter 3

Dal, the Catalan Avant-Garde and Anti-Art

Chapter 4

Un Chien Andalou

Chapter 5

Dal, Surrealism, Documents and Freud

Chapter 6

Painting and the ParanoiacCritical Method

Chapter 7

Dals Mythologies

Chapter 8

The Surrealist Object, Installations and the Stage

Chapter 9

Dal and the Cinema

Chapter 10

Leaving Surrealism

Chapter 11

History, Tradition and War

Chapter 12

Dals Post-War Painting

After Picasso, Salvador Dal is probably the most universally famous, which is not to say the most highly regarded, twentieth-century painter. Not least among the reasons for this was his talent, extraneous to his abilities as a painter, for publicity. He has been frequently identified with Surrealism, and to a large extent even determined its popular image; yet he was eventually rejected by the movement itself. Perhaps his most celebrated painting, Christ of Saint John of the Cross (1951), is fundamentally opposed to Surrealism in spirit.[] One reason for his popularity is the widely held opinion that he was an extraordinarily technically gifted painter and a brilliant draughtsman. But this was not the reason for his initial success with the Surrealist group, and Dal himself was less than flattering about his own talents. He claimed that it was always the idea that was most important. The medium for its expression and he was as fluent in words as he was in paint was a matter of relative indifference for him. Dal considered his technique to be no more than a vehicle for conveying the disturbing imagery of his work, which, based initially on psychiatry textbooks and the comparatively new science of psychoanalysis, opened up new subject matter for painting.

The 1970s and early 1980s, when I was working on the first edition of this book, was the stone age in Dal studies by comparison with today. Dal himself was still alive, and the Teatre-Museu Dal in Figueres was in its infancy. There were copious but not wholly reliable sources for a student of his work, mostly written by Dal himself, including The Secret Life of Salvador Dal, his essential autobiography, important also for its meaningful falsification of memory, as Andr Breton put it. There were things amiss with the first edition of this book in 1982, including some howling errors of dating. It was also, chronologically speaking, unbalanced: a great deal more space was given to the paintings of the 1920s and 1930s, and to the relationship with Surrealism, than to the four decades of work from 1940 to his death, or to those other aspects of Dals packed life and multifarious activities that have subsequently received a good deal of attention. I was clearly happiest talking about the paintings of 1929 as the peak of his achievements.

My belief at the time was that the controversial, commercial, celebrity-loving, publicity-hungry Dal of the post-war period was blinding people to the earlier, brilliant artist, and his reputation needed to be rehabilitated. Controversial hardly does justice to Dals positions at the time. He seemed to have ruled himself out of the history of art by not conforming to the tenets of Modernism and burning his boats with Surrealism, and had offensively aligned himself with Franco and the Fascists. The pendulum swung for a while after his death towards an appreciation of the Surrealist Dal, but the later work was dismissed. In recent decades it has swung again. Publications have begun to do justice to his whole creative range, not least his writing and his late paintings. His unflagging commitment to painting, dazzling variety of styles, determination to combine the scientific revolutions of the twentieth century with metaphysics (rivalling science fiction), experiments with new visual technologies that stretch from his early championing of film and photography to holography and video, and extension of the artist brand into popular culture resonates today with new audiences.

When Dal died in 1989, he left a number of treasures, many unknown, in his three homes the Teatre-Museu, Portlligat and the Castle of Pbol including working drawings, discarded paintings and piles of semi-forgotten manuscripts. These have passed through a period of retrieval and consolidation: there is now an excellent archive and full and freely accessible online catalogues raisonns of the paintings and sculptures, published by the Fundaci Gala-Salvador Dal (FGSD) in Figueres, indispensable accompaniments to this revised edition. The two museums dedicated to his work, the FGSD and The Dal in St Petersburg, Florida, backed up by extensive research and some great exhibitions over the last few decades, have transformed the understanding of this brilliant and complicated artist. Another invaluable source of information about Dals life is the most comprehensive biography to date by Ian Gibson, published in 1997. Unfortunately, Gibson took a strong dislike to his subject and never missed an opportunity to put the boot in, as indicated in the title of his bestseller: The Shameful Life of Salvador Dal. In some ways it is lucky that he was not very interested in the paintings.

A new book would be needed to digest and re-present all of these advances on the scale possible in the World of Art Series. So, within the limits of a new edition, I have tried to rebalance things, emphasizing continuities in Dals output and extending a little the discussion of his later works, though they are undoubtedly still short-changed. I particularly regret not having given more time and attention to Gala; Dal added her name to the signature of many of his paintings, signing Gala-Salvador Dal, acknowledging her absolute centrality to his life and work after their meeting in 1929. One came across her, apart from in Dals own ecstatic homages, in her careful transcriptions (she had unmistakable handwriting) of Dals texts in his eccentric and phonetically spelled French, and in the letters and postcards to friends and patrons such as the de Noailles and Edward James. But though she was evidently a mesmerising woman, whom her first husband, the poet Paul luard, never forgot, and who enchanted Max Ernst, she was extremely private. She seemed to have left no personal record until a notebook was found in Pbol. The

Next page