Helen Lundeberg (19081999), Blue Planet, 1965

About the Author

Dawn Ades is Professor Emerita of the History and Theory of Art at the University of Essex. She has written extensively on Dada, Surrealism, photography and women artists, among other things. Publications include Dada and Surrealism Reviewed (1978), Photomontage (1976), Dal (1995), Writings on Art and Anti-Art (2015) and Marcel Duchamp (with Neil Cox and David Hopkins, 2021). Among the exhibitions she has organized or co-organized are Art in Latin America (1989); Fetishism: Visualising Power and Desire (1995); Salvador Dal: The Centenary Retrospective (2004); Undercover Surrealism (2006); and Dal/Duchamp (201718).

Contents

Photomontage was first published in 1976, and a new edition appeared in The World of Art series in 1986. In this second edition, the considerable amount of critical and historical materials published in the intervening years, in particular in relation to Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism, were brought to bear on the text; new material was included where appropriate, retaining the emphasis on photomontage in the 1920s and 1930s; and certain sections were revised. A thematic structure with chapters replaced the single text, and the images were integrated rather than being massed in a block at the back of the book. However, the format of the pages was considerably smaller than in the original, which led to the compression of some of the images, a problem that has as far as possible been rectified here. Otherwise, the themed chapters in this revised edition are the same. Some more recent material has been added and some earlier omissions made good, but by no means all; adequately to cover these would require another book.

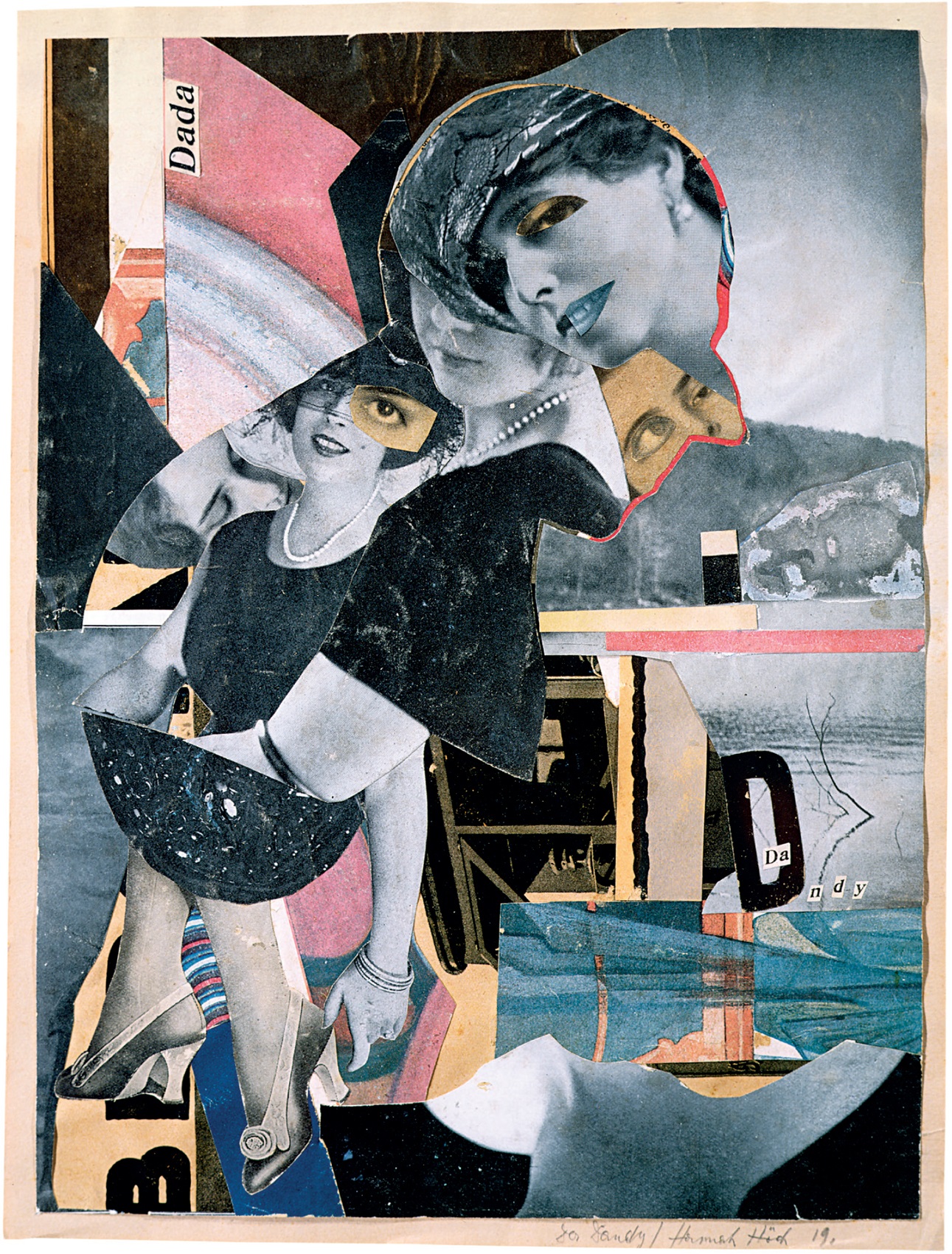

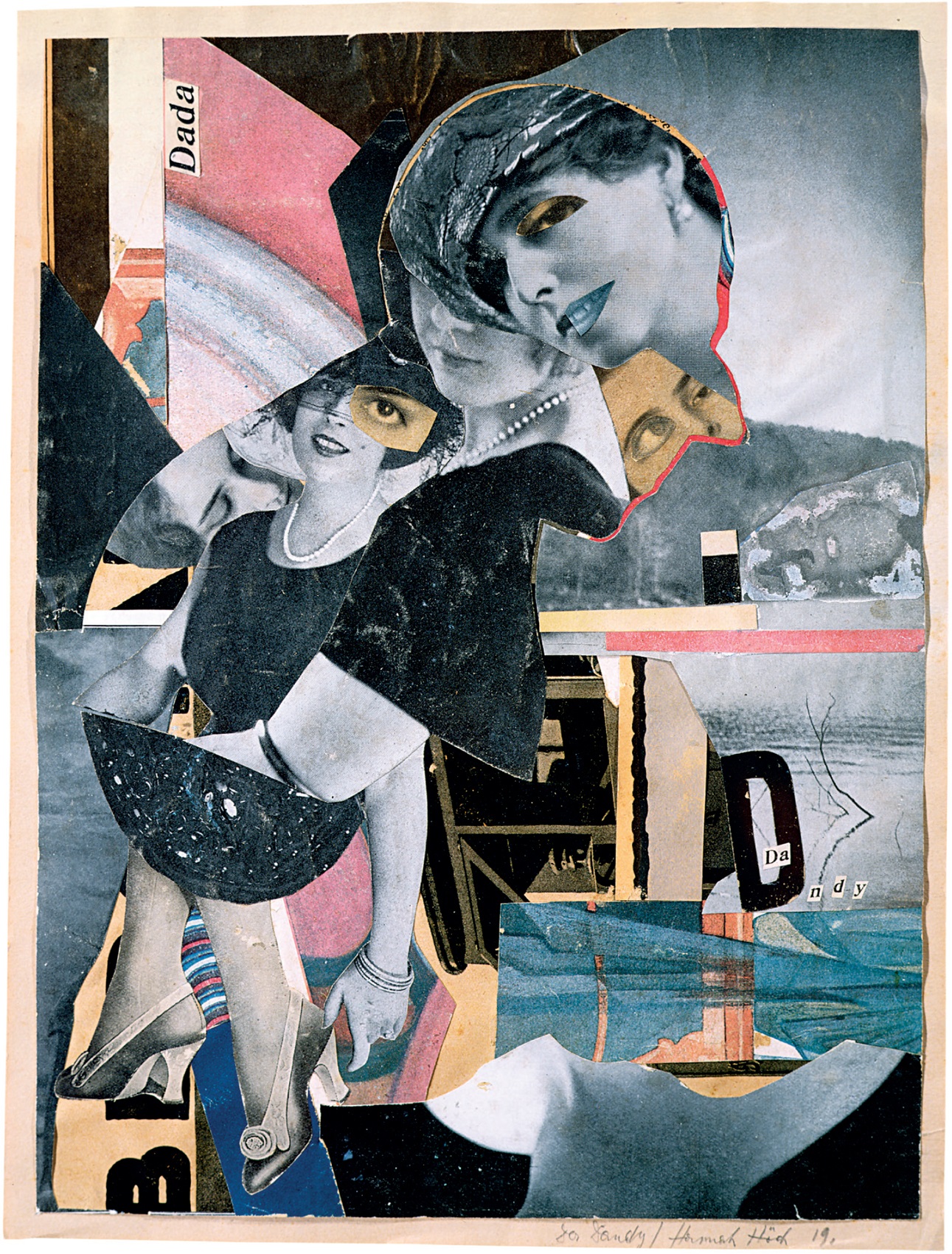

The original publication of Photomontage coincided with a surge of interest among artists in the possibilities of photomontage. The work of some of those who reactivated photomontage in the 1970s, notably Linder, is included in this new edition. Linder told me how important the book had been for her, as a student in Manchester: Musically, sartorially and graphically, we started to cut things up we cut up our hair, our coats and our magazinesI dont think you could have choreographed the timing of Photomontage any better.

Revisiting photomontage for this new edition both my book, and the subject itself has highlighted changes in visual culture that deserve comment. The first is to do with technological developments, with the primacy now of screen over print, and the incredibly sophisticated advances in digital imaging. These have an interesting relationship with the practices of photomontage, the effects of which they can seemingly replicate. Almost anything can be visually manipulated, re-cast and re-combined with the resources of photoshop or other similar and even more advanced programmes. Secondly, over the last few decades the term photomontage in art history and exhibition and museum labelling has been widely replaced by collage. The implication in both cases is that photomontage has had its day, if it ever had one. Apparently, it has been overtaken by technology and expunged from history.

If this were the case, a new edition of this book would have little other than a certain archival interest. But it seems to me that photomontage remains a term with deep critical significance, and retains considerable ongoing traction as a practice. Alright, define it then, you may say. Definitions of photomontage (subsequent to its first appearance) are legion and contradictory; they are scrutinized in the Introduction (

So photomontage should have an identity distinct from collage but what about its position regarding new technologies, which could be seen as having usurped its place? Digital manipulation can mimic the effects of photomontage, but it cannot replicate the final physical and material effect of the encounter with the found images. In some ways digital images are best compared to the earliest manipulations of photography and its attempts to create a realistic image, whether of a natural scene or an idealistic or mythological one. Advances in digital image-making are mostly in the direction of persuading the viewer of the veracity of what they are seeing, often in the interests of commerce or politics smoothing out the sutures, convincing the viewer of the truth of its presentation. The deepfakes of today are a direct descendant of the tampered negative or airbrush that allowed, for example, Stalin to erase Trotsky from the photographic record of the Communist Party. Photomontage, by contrast, has a critical or transformative purpose in the juxtaposition of images: their apparent significance or intention is under scrutiny.

Since Photomontage first appeared in 1976, changing conditions around image copyright have affected both the practice itself and the publication of the works. While the rights of visual artists over their own work quite rightly need protecting, copyright issues have also impacted certain artistic processes, of which photomontage, insofar as it can be a kind of appropriation, is one. This has changed access to and use of images in a totally unforeseen manner.

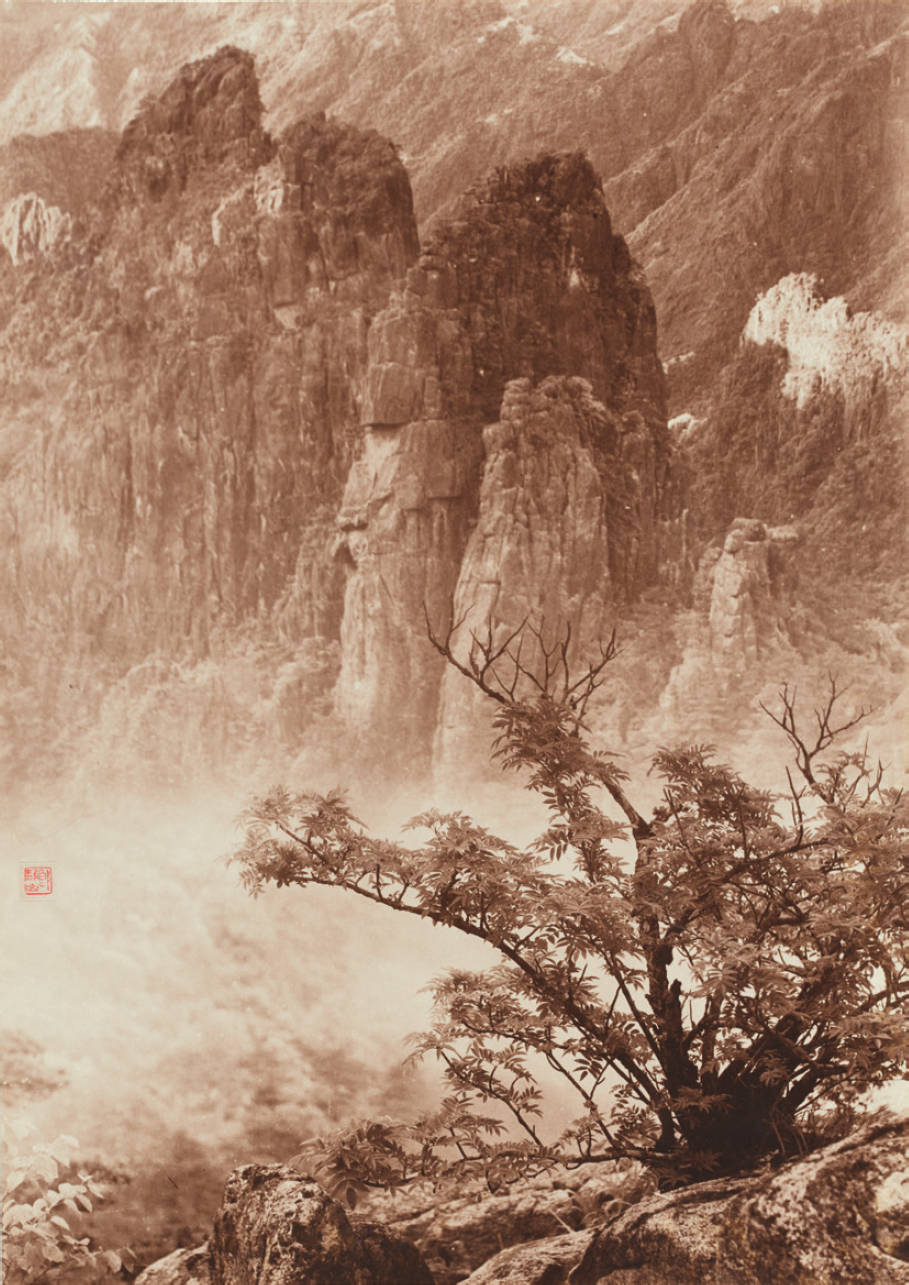

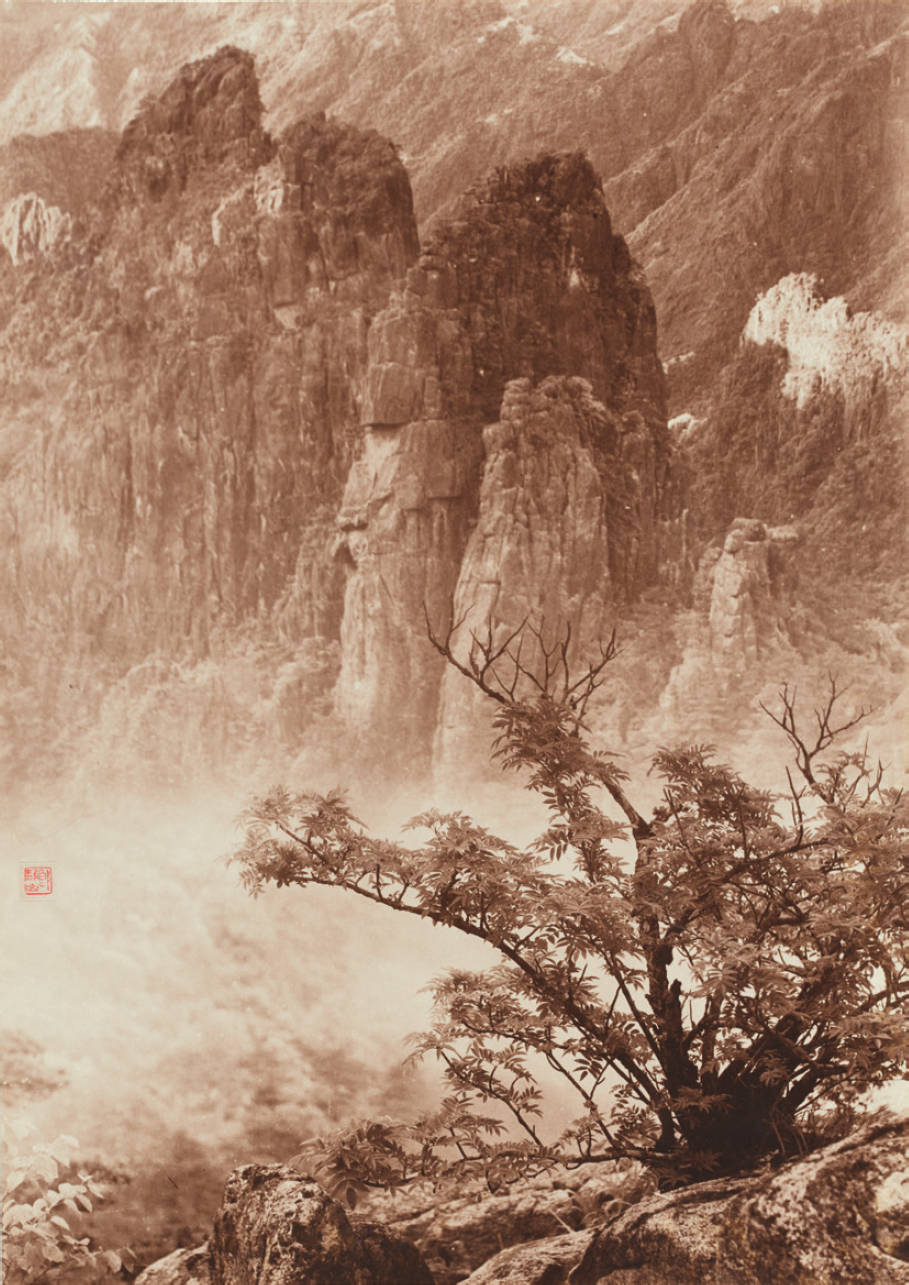

Photomontage, in various of its many possible forms, has accompanied the development of photography and its ambiguous relationship with painting all over the world. For example, Lang Jinshan, a pioneer of photography in China, developed a subtle method of superimposing different images onto a single print to create scenes that look remarkably like Chinese landscape paintings. The liberties taken with scale and the conjunction of different images might first be ascribed by the viewer to the traditions of Chinese landscape painting rather than to photographic manipulation.[]

Lang Jingshan Majestic Solitude, 1934

A more recent work, also by an artist based in China, takes aim at the relationship between a very different painting tradition (Socialist realism) and photomontage, as well as at artistic fashions and ingratiating politics. What appears at first sight to be a news shot of Mao admiring Marcel Duchamps Fountain is quickly re-registered as a photomontage, with Mao inserted in a realistic way, rather like a deepfake video; but in fact, Shi Xinnings image is a hyperrealist painting.[]

Shi Xinning, Duchamp Retrospective exhibition in China, 20001. A painting mimicking a photomontage pretending to be a photograph of an unexpected encounter.

Manipulation of photographs is as old as photography itself. One of the earliest photographic processes, Henry Fox Talbots photogenic drawing, developed during the 1830s, involved the direct contact-printing of leaves, ferns, flowers and drawings, and was rediscovered and put to use with an almost infinite repertoire of objects by Man Ray, Christian Schad and Lszl Moholy-Nagy in their photograms of the 1920s.[

Next page